Russia’s now-notorious foreign agent law – a key tool for repressing independent media – first emerged ten years ago, in July 2012. Its development provides a unique lens for tracking the expansion of authoritarian control within the country. Long abused by the government, the law was instrumental in causing self-censorship and a mass exodus of domestic and international outlets from Russia, as well as forcing the remaining independent media organizations underground.

On June 28, 2022, the state-owned Russian Public Opinion Research Center released the results of its poll on what ordinary Russian citizens associated with the term “foreign agent”, a status now applied to almost all members of the independent media. 61 percent of respondents indicated that the term had negative connotations, while only two percent saw it in a positive light (11 percent found no association with the term, and 24 could not answer).

Amongst the negative connotations, 14 percent of respondents associated it with the word “spy”, seven percent with “traitor of Russia”, and six percent with the Stalin-era term “enemy of the people”.

Despite its origins, the poll reveals a key objective of the foreign agent label. “The law’s main aim is the same as when it was created: It is to silence civil society actors such as NGOs and members of the media and to make their life much more complicated”, said Daria Korolenko, a lawyer for the independent Russian human rights media project OVD-Info, in an interview with IPI. Ten years on, its aim has not changed.

A worrying evolution

The law’s origins and its continued expansion were tied to the Kremlin’s fears of growing domestic dissent. Its evolution both prior to and following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine provides a timeline for the growing censorship and curtailment of press freedom that accompanied the increasingly aggressive stance of the Kremlin regime, both at home and abroad. As Aleksei Obuhov, editor of independent outlet SOTA, told IPI: “Internal repressions occurred in parallel with preparations for external aggression.”

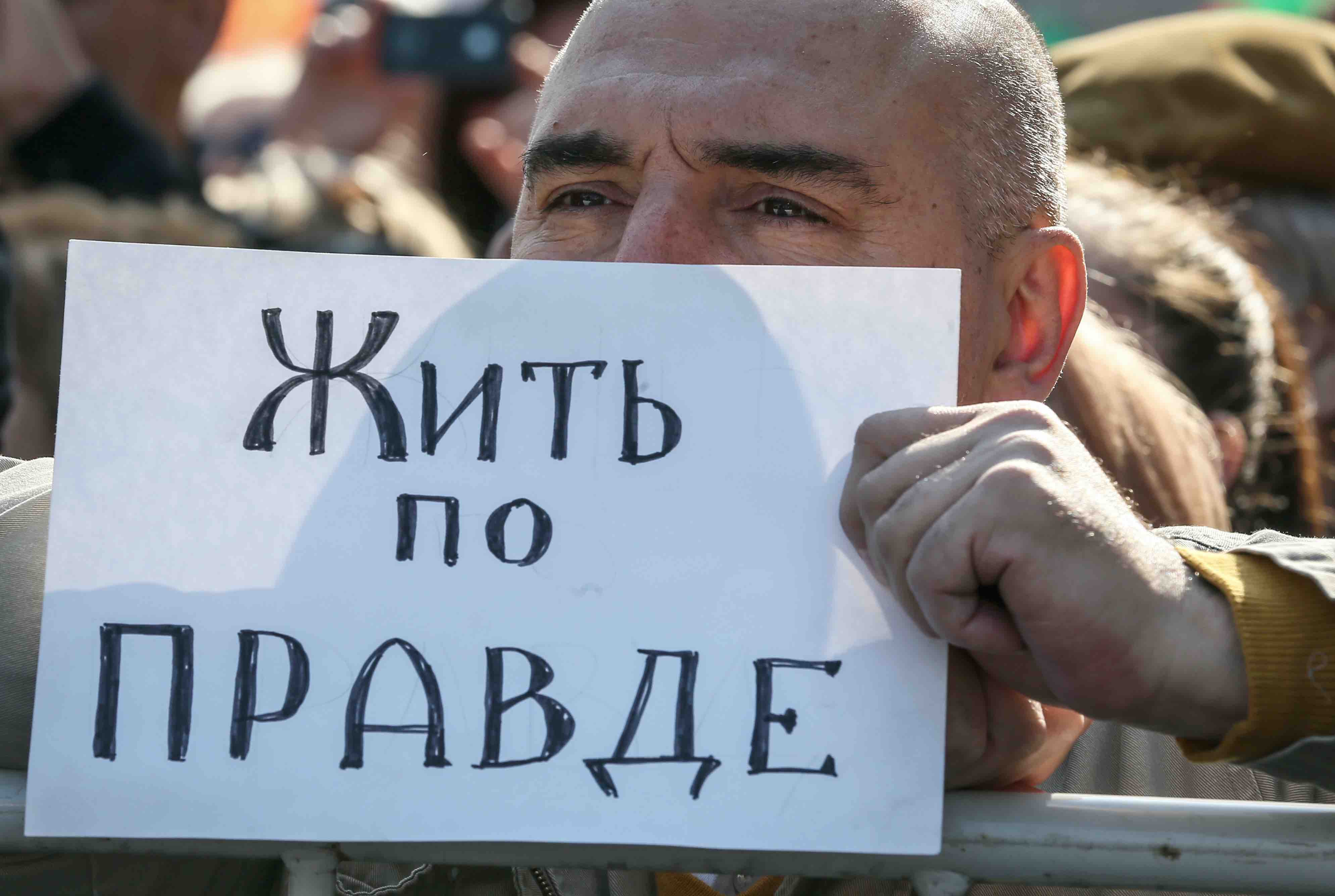

Against the backdrop of the largest protests against election fraud that Russia had seen since the fall of the Soviet Union, the foreign agent law was first passed in 2012. At the time, it was aimed solely at foreign-funded non-commercial organizations that the authorities deemed to be engaging in political activities. The law required such entities to register themselves as foreign agents and disclose their status in all online publications.

It proved devastating for independent NGOs. The targeting of leading human rights NGO Memorial and its subsidiaries from 2014 to 2016 exemplified the law’s abusive nature. As with most other organizations designated as foreign agents, Memorial’s criticism of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and domestic repression had placed it in the authorities’ crosshairs.

From 2012 to 2016, 170 organizations were labeled as foreign agents, as reported by OVD Info.

By leaving the definition of political activities purposefully broad, the authorities ensured the law’s applicability to a broad range of dissidence, paving the way for its future expansion. “All repressive Russian laws are formulated very vaguely, the authorities can implement them however they want”, said Andrei Shary, the director of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s (RFE/RL) Russian service, in an interview with IPI. “It means that in practice you don’t know what you have to do. It creates an atmosphere of fear.”

By 2017, amidst massive anti-corruption protests organized by opposition leader Alexei Navalny, the law was expanded to include news outlets. Once placed on the list, outlets became subject to immense financial pressure and legal scrutiny. Aside from forcing media organizations to hand over extensive financial documentation to the authorities on a quarterly basis, the label led to curtailed cooperation with government institutions, civil society organizations, and others afraid to be associated with a “foreign agent”.

Designation as a foreign agent became synonymous with the label that targeted media were required to include in their publications: “This message (material) was created and (or) distributed by a foreign media organization, fulfilling the functions of a foreign agent, and (or) a Russian juridical figure, fulfilling the functions of a foreign agent.”

While at first the law targeted foreign media outlets that were funded by foreign governments, such as RFE/RL, its progressive expansion soon began to threaten independent media outlets in general, including domestic ones. The concept of receiving funding from abroad, ostensibly a key prerequisite for inclusion on the list, was watered down to become a catch-all. Going on a press tour or an international conference paid for by a foreign organization, or even receiving money from a relative or friend abroad, was enough to be declared a foreign agent.

At the end of 2019, the passing of an amendment allowed for individual persons, not just legal entities, to be included in the list of media organizations acting as foreign agents. Journalists Liudmila Savitskaya, Sergey Markelov, and Denis Kamalyagin were among the first to be included in the list. All three had collaborated with RFE/RL. As a result of the law’s expansion, many became afraid to collaborate with outlets labeled as foreign agents.

In the wake of the 2021 protests against the jailing of Navalny, the law was once again expanded. Any outlet that republished information created by foreign agents without disclosing their status could be fined.

The expansion accompanied the largest crackdown on media organizations in decades. Leading independent Russian outlets like Meduza, Mediazona, and Republic, as well as the country’s largest online independent broadcaster, Dozhd, were designated as foreign agents. OVD-info was also placed on the list, coming under immense administrative scrutiny as a result. In an interview with IPI last year, Meduza’s founder and CEO, Galina Timchenko, stated that “even a simple interview or comment could lead you to be declared as a foreign agent.”

There could no longer be doubt: the foreign agent law was not about regulating foreign funding – it was, and remains, a tool for arbitrary repression of independent media

By the end of 2021, around 1,500 activists and journalists had been forced to flee the country. Over 100 legal entities and individuals had been designated as media organizations acting as foreign agents. Those remaining were often forced to engage in self-censorship simply to continue their operations.

The invasion of Ukraine

The commencement of full-scale hostilities in Ukraine revealed the effects of the law and other accompanying forms of media censorship. By now, the Russian media space was completely dominated by pro-governmental outlets.

“The country had no problems (there was no one left to talk about them), and minds began turning to foreign victories”, said Obuhov. “The beginning of the war, in itself, caused the emergence of wartime censorship (with the truth coming only from the Ministry of Defense and Putin). Thus, lies gave birth to the war, and the war itself gave rise to new lies.”

Said wartime controls paved the way for the most recent expansion of the law, whereby the lists of media and non-commercial organizations, as well as individuals acting as foreign agents, were combined into one common database.

The new expansion has removed all ostensible restrictions on the law, long abused by the authorities anyway. Alleged financing from abroad is no longer necessary, merely being subject to “foreign influence” can now land someone on the list.

“The authorities were satisfied for a while with Navalny, now they are going after everyone,” stated Shary. “They want everyone to feel insecure and threatened, and from this point of view, the legislation for foreign agents is almost perfect. I know from my personal experience, as it is difficult for us to find collaborators in Russia. We are not cited by local media because no one wants to meddle with foreign agents.”

As Korolenko pointed out, while 70 people were recognized as foreign agents in 2021, since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 50 additional people have been placed on the list. “Any person who speaks out about the war is liable to be labeled as a foreign agent”, she said.

The slow strangulation of press freedom

The foreign agent law is now firmly embedded in the infrastructure of censorship at the disposal of the Russian government, but in many ways its evolution points to the origins of numerous other authoritarian controls. As with most repressive measures by the Kremlin, while initially narrow in scope, the law was progressively expanded through legal changes and arbitrary application whenever those in power felt threatened.

The ten years since 2012 have witnessed a return to Soviet-style controls over press freedom. Accompanied by an intensification of pro-government propaganda and an increasingly aggressive stance abroad, the evolution of the foreign agent law in many ways mirrored the development of Russia’s authoritarian regime.