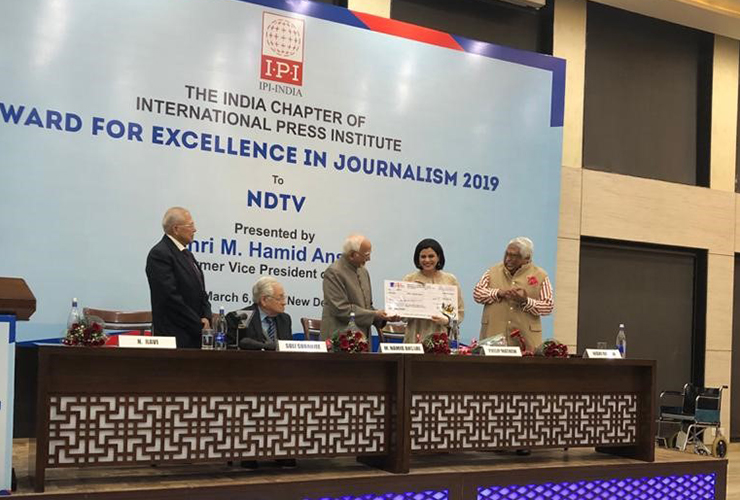

Last year, the International Press Institute (IPI)’s Indian National Committee presented its 2019 Award for Excellence in Journalism to private news channel NDTV for an investigation into the murder of an eight-year-old girl in Kathua, Kashmir in January 2018.

The girl belonged to a Muslim nomadic tribe, while the men accused of the crime were all Hindus, which raised communal tensions in the region and sparked protests in defence of the accused. The leaders of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) openly participated in protests.

“The award is for the expose of the conspiracy to scuttle probe into the heinous Kathua rape and murder, and a strong expose of the political hypocrisy across the political spectrum”, the Indian National Committee said in announcing the award last November, calling the story “representative of excellence in journalism.”

The investigation was led by senior anchor Nidhi Razdan. In a recent interview with IPI, Razdan delves into the reasons behind her decision to follow through with the story and controversies and challenges surrounding the case. She also talks about the wider media environment in India, her experience as a woman journalist, and recent challenges Kashmir journalists face.

IPI: What did the IPI India award mean to you?

NR: First of all, the award was a great honour and a recognition of our work on a very difficult story, but I think that what made the award particularly special is that it came at the time when we are seeing free press facing a lot of challenges in India. NDTV has stood as a beacon of the free press. As a leading TV channel, we have seen a lot of pressure from many quarters to try and shut us down and many attempts to bully us. We are going through a difficult time, but we survived. I think that an award like IPI gives us international recognition for the kind of work we are doing and for why as an organization we need to be here, to stay alive, and to stay relevant in journalism. It comes in this larger environment of media intimidation we see in India.

IPI: What were the reasons behind your decision to take up the investigation into the case?

NR: All the rapes and murders are horrific, but I think that this one was even more horrific for two reasons. First, because of the nature of the crime itself and the young child it involved. Second, because there were ministers in the government in the state openly coming out and rallying in support of the accused. The political conspiracy that followed and attempts to cover it up and drive a wedge between communities made the case so outrageous. My colleagues Nazir Masoodi and Zafar Iqbal really did a lot of great work going to the spot where it happened, tracking the family down. We didn’t take our eyes off the story even when it naturally faded from national headlines and I think that this helped keep the story alive in the national media as well.

IPI: What types of challenges did you face while covering the story?

NR: The challenges were the same as for most stories: online trolling, bullying, and harassment one faces especially as a woman journalist. There was an entire lobby here in India saying that this never happened, and that the accused was set up and framed. This is a general trend: If there is a particular group that doesn’t like the story you’re doing or you asking difficult questions, then the modus operandi basically is to slander you, get after you, abuse you, bully you online. This is pretty much what we faced as well, me included.

IPI: In the introductory chapter of the book you edited “Left, Right and Centre: The Idea of India” you talk about “the new normal”, a pervasive neo-nationalism and related discourse. How the circumstances of this case fit into “the new normal”?

NR: It is a larger general environment of ultra-masculine nationalism that we’re seeing. Unfortunately, that has come to be defined with Muslim-baiting in this country. That’s what happened in this case as well, somehow to be nationalist is to be defined as someone who is marginalizing the Muslim community, blaming them for everything. Even now in the coronavirus. I do see it as part of the same stream. This is not how I define nationalism, but many people do see it like that, and this is an extension of that.

IPI: How grave would you say that the problem of politicization in the Indian media?

NR: Everything is politicized here, unfortunately. I don’t think there is anything wrong with politicizing a lot of issues. To me, for example, violence against women should be politicized, I wish it was a political issue that would make policy makers sit up and take notice of what do we need to do. However, I wish it wouldn’t be communalized. I wish that the religion of the victim or the perpetrator didn’t matter because it shouldn’t matter.

Rape is all-pervasive in our society and it is irrespective of religion. The discourse has become so divisive and so vicious, frankly. Because this child was from a certain community, you saw another community vilify her and her community. That’s when I feel humanity dies. These crimes do not see religion in that way, and those who supported the accused did see the religion and rallied around the accused. This gets exemplified in social media through hashtags. I remembered being trolled, “Why do you take Asifa’s case, what about this other rape case?”. I kept saying and screaming, “All rapes and killings are wrong, but in these other cases ministers and the government did not come out and supported the accused.” This was the difference in this case, it is what made the case more horrendous and outrageous. It is another feature of that masculine nationalism that we are seeing.

IPI: What problems and challenges do women journalists face in India?

NR: One of the great things about Indian journalism has been that women journalists are very much at the frontline of reporting, whether it’s politics, defense, foreign affairs. There is a whole generation of women journalists who have covered politics in India and who have been pioneers paving the way for the rest of us to be able to do it. This doesn’t mean that women do not face problems, sexism, harassment. I have been fortunate not to face it because I’m working in an organization that is actually driven by women, where most of the editors are women. We are a very different organization in that sense, so I never had to face the problems I heard had happened in other organizations. So those challenges do exist, but I am proud of the fact that in this country women have been pioneers and continue to be part of the media and very good journalists.

IPI: What is your opinion about the recent developments in Kashmir and challenges media in the region is facing?

NR: I think the media in Kashmir is facing a very difficult time. After the special status of Jammu and Kashmir was taken away last August, we saw an unprecedented crackdown in the region, and not just in media. The media, however, face the brunt of it, in terms of intimidations, harassments, censorship. We saw the impact of this, a lot of the local press stopped writing about the crackdown and started writing about olives growing in some part of Europe, or about something as silly as that. It was great to see three photojournalists from Jammu and Kashmir winning the Pulitzer for the work they had done after August last year. Journalists in this region continue to face challenges, there is no high-speed internet, and the circumstances under which they work during the pandemic lockdown are terrible. No phones were operating for a couple of months, I mean, just to get their stories out to their bureaus in Delhi.

My heart goes out to them for being able to report, those who did, under these difficult circumstances. Let’s face it, state intimidation is very different there. That model is now being replicated in other parts of the country. Just today a journalist in the state of Gujarat was slapped with a sedition case against him for a political story he did that in no way amounts to sedition. The state is using its iron hand here. I have a lot of respect for my colleagues in Jammu and Kashmir who have been through a lot of pressure and worked in very difficult circumstances and continue to do so for just being able to report the story.