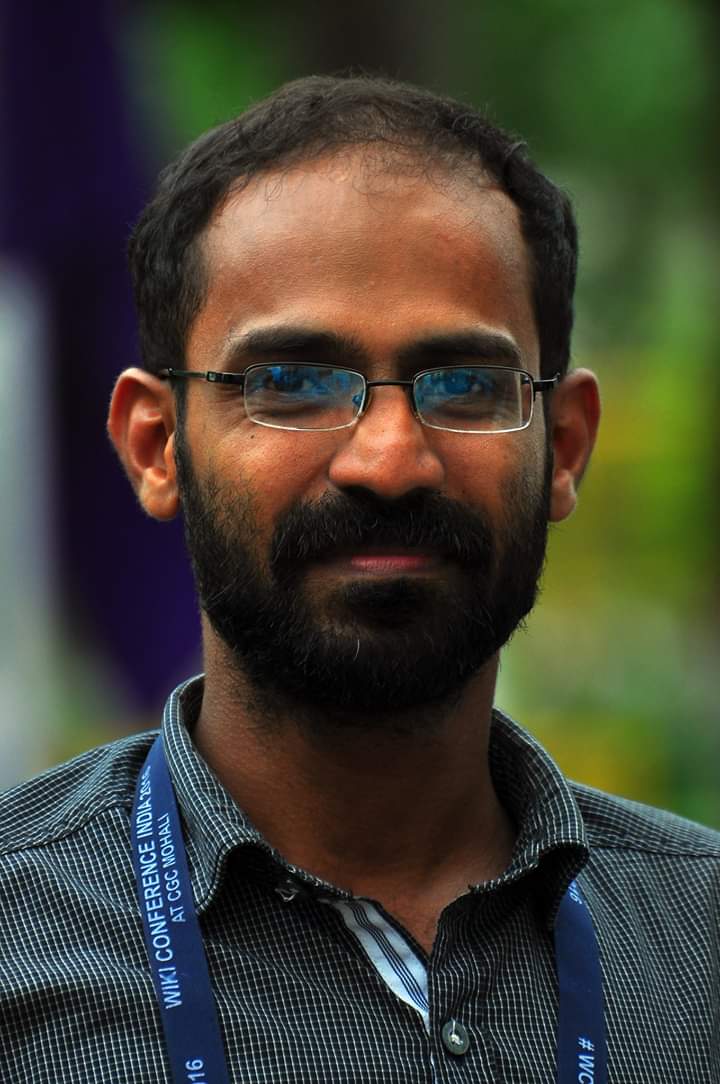

On October 5 last year, Indian journalist Siddique Kappan was on his way from Delhi to Hathras, a town in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, to report on an alleged gang rape and death of a Dalit woman. The attack had caused protests and public outcry all over the country. But before Kappan could reach his destination, he was arrested and jailed.

Nine months later, Kappan, who is originally from the southwestern state of Kerala, is still detained under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and Information Technology Act, awaiting trial. He is charged with promoting enmity between groups, outraging religious feelings, sedition, conspiracy and raising funds for a terrorist act.

“Kappan was denied bail on July 6 in the District Court of Mathura”, Kappan’s lawyer, Wills Mathew, told IPI last week. “The next step will be a bail hearing in the High Court. For cases under the UAPA, especially terrorism charges, it is very difficult to get bail in the District Court. We have better chances at getting Mr. Kappan out on bail from the High Court.”

But why is Kappan in prison at all? Kappan’s lawyer; his wife, Raihana; as well as an Indian journalist working on the case who requested anonymity all say that Kappan was on his way to the town of Hathras in order to interview the victim’s family – that he was simply trying to do his job as a journalist.

Family denies ties to extremist group

Raihana Kappan told IPI that, due to their limited financial situation, her husband’s only affordable way of transportation to Hathras was to try and find a shared car ride with other people going in the same direction. Siddique Kappan, who has been a journalist for a decade and currently works with the Kerala news portal Azhimukham, drove towards Hathras with three other men.

One of the passengers was allegedly an activist with the Popular Front of India (PFI), which is considered to be a right-wing extremist Muslim organization in India but is not currently banned. Another passenger was allegedly a journalism student who was part of a student organization of the PFI. The third person in the group was the car’s driver. Before the group could reach Hathras, they were stopped and arrested at a toll plaza in Mathura, an adjoining district.

Police have accused Kappan of being part of the PFI and say they suspected he planned to create unrest in Hathras. However, IPI interviewed several sources close to Kappan, including his wife, who denied the journalist had connections to the PFI.

According to Kappan’s wife, in the first 24 hours after his arrest nobody knew what happened to him or where he was. She also claims that Kappan was physically assaulted during the interrogations, deprived of sleep, and had his glasses taken away from him. The day after his arrest the Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ) filed a habeas corpus petition demanding his release. Kappan is the elected secretary of the Delhi unit of KUWJ. He was officially charged on October 7.

Months of ill-treatment

For over a month after his arrest neither Kappan’s family nor his lawyer was able to communicate with him. According to Raihana Kappan, he was housed with 400 to 500 other inmates in a crowded school building in inhumane conditions. Later Kappan was moved to Mathura jail, where the conditions were better, and he was allowed to talk to his family over the phone once a week.

Meanwhile, Kappan’s mother’s health deteriorated. Eventually the Supreme Court allowed Kappan to visit her briefly in February 2021. The visit had strict restrictions: Kappan was not allowed to talk to the media or leave his home and he was under armed police guard at all times.

In April Kappan contracted COVID-19 in Mathura jail and fell very ill. According to his wife, Kappan was transferred to a hospital in Mathura where the conditions were horrid: Kappan was chained to a bed without the possibility to use the bathroom. After his family and KUWJ approached the Supreme Court, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, and MPs from the United Democratic Front over the situation, Kappan was taken to another hospital in Delhi but soon after transferred back to Mathura jail.

According to wife, Kappan is diabetic and has a heart condition, which makes him a COVID-19 risk patient. Even though Kappan’s family travelled all the way from Kerala to Delhi to visit him when he was unwell, they were not allowed to see him.

Kappan’s mother passed away in June, but Kappan was not allowed to attend her funeral. According to his wife, Kappan still has health issues, such as a broken jaw from falling down in the jail bathroom, but is recovering.

Why Kappan?

The brutal gangrape and murder of the Dalit woman in Hathras, her forced cremation by the Uttar Pradesh police, and the ensuing protests were widely reported in India – despite efforts by local officials to prevent coverage. The Uttar Pradesh authorities banned journalists from entering Hathras and didn’t allow the victim’s family to talk to the media for the duration of the investigation.

Yet of all the journalists who attempted to cover the case, Kappan is the only one who has faced detention – let alone the horrific treatment and lengthy court proceedings he has endured.

Kappan’s wife and the Indian journalist IPI interviewed suspect that Kappan might have been targeted because of his work. They pointed to critical stories about politics and crime he has written in the past. “He is a Malayali Muslim and a journalist. That is a deadly combination in this country”, Raihana Kappan said.

“Kappan is a journalist and that is most likely part of why he is in custody. Journalists should be able to talk to people from all walks of life and do independent journalism without being targeted by the authorities”, Kappan’s lawyer, Wills Mathew, said. Raihana Kappan and Mathew emphasized that Kappan was not a member of PFI or working for the organization.

Mathew met Kappan the last time three weeks ago. “He is a strong, committed person. I talked with him for half an hour”, Mathew said.

Press freedom under threat in India

Kappan’s arrest occurs amid a wider press freedom decline in India. In particular, legal harassment against journalists in India has been on the rise in recent years. Several charges of sedition have been filed against journalists for their critical reporting about the national and state governments in the country. The COVID-19 pandemic has also negatively affected journalistic freedom. Journalists have been targeted by the authorities for their critical reporting regarding the state’s pandemic response. In addition to legal cases, journalists have been victims of police violence during the lockdown.

“Even anti-government reports in the media are seen as an act of sedition, which are non-bailable offences” Sanjay Kapoor, the editor of Hardnews magazine, told IPI. “Since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power there has been a spike in the number of sedition cases filed against journalists.”

Kapoor noted that the Supreme Court recently overturned a case against a senior journalist and suggested certain safeguards to prevent large scale arrests of journalists. “Having said that there is one editor, a litigant against sedition laws, in jail for a Facebook post. Actions such as these have a chilling effect on media freedom.”

NDTV reported on July 12 that a group of 74 former police officers and bureaucrats wrote an open letter accusing the Uttar Pradesh authorities of violating the rule of law. The statement brought up, among other issues, arbitrary detentions, police brutality on peaceful protesters, the targeting and discrimination of Muslim men, and misuse of the National Security Act. Kappan’s case was mentioned in the letter as an example of what the signatories said was the Uttar Pradesh government’s bias against Muslims.

“IPI calls for the immediate release of Siddique Kappan, and we strongly condemn the unacceptable ill-treatment he has received at the hands of the authorities as well as the apparent deprivation of his basic due process rights”, IPI Deputy Director Scott Griffen said. “We are extremely concerned that Mr. Kappan was targeted and detained due to his journalistic activity. In the absence of evidence justifying these accusations, all charges against Mr. Kappan must be immediately dropped.”

“The growing targeting of critical journalists in India is extremely concerning. All journalists in the country must be able to safely cover events in the public interest, without fear of harassment, detention or discrimination.”