By IPI Advocacy Officer Jamie Wiseman

Few terms have become so engrained in global political discourse in the last half decade than that of so-called “fake news.” The widely used yet ill-defined phrase has become a messy shorthand enveloping everything from social media rumours, to online political disinformation, to state-sponsored internet propaganda.

With vastly different motives, in the last few years states around the world have begun passing new laws that allow authorities to regulate what they deem dangerous and inaccurate content online, often under the banner of combating disinformation or so-called “fake news”.

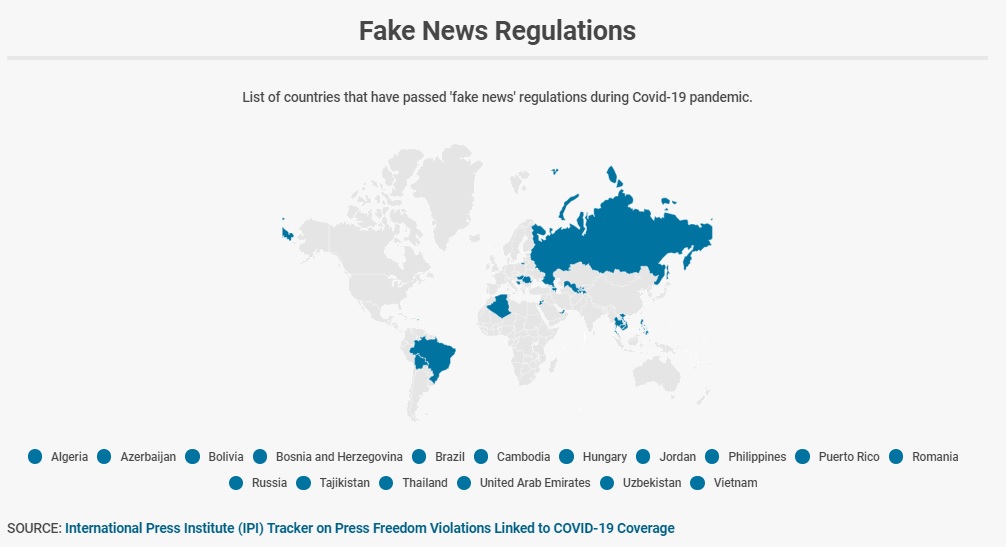

As with so many other things, this trend has been intensified by the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the last eight months, IPI’s Covid Tracker has documented at least 17 countries worldwide in which some form of legislation or decree has been passed against “online misinformation” or “fake information”.

With global levels of press freedom in decline, in tandem with shrinking digital freedoms, this domino effect of “fake news” laws brings with it serious risks.

On the one hand, while many of these laws stem from an understandable desire to combat falsehoods, their vague definition and broad scope means that they can be easily manipulated to censor critical reporting. On the other hand, states that have no genuine interest in protecting quality information use the fight against disinformation as a pretext for laws that limit critical speech.

For illiberal leaders who have long sought new methods to suppress independent media and dissent online, the health crisis and subsequent “infodemic” presented an opportunity to rush through laws without scrutiny and add another tool to their legislative arsenals.

Of course, not all laws passed during the pandemic have been used against the media. In some cases, public pressure and constitutional checks on power ensured that disproportionate laws against disinformation – or other disproportionate emergency measures – were withdrawn or limited to being valid only during the state of emergency.

As IPI’s global monitoring has shown, however, in more autocratic states new laws were written permanently into criminal or civil codes and outlawed all forms of online misinformation, with vaguely defined provisions allow prosecutors to charge or fine journalists for publishing information deemed untrue or threatening by authorities. Such laws have created new possibilities for authoritarian leaders, and their law enforcement and judicial systems, to place restrictions on speech that may long outlast the pandemic.

!function(e,i,n,s){var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”);

IPI Deputy Director Scott Griffen said that while no two pieces of “fake news” legislation passed since the outbreak of Covid-19 were identical, all ultimately posed a threat to press freedom in their capacity for misuse.

“Disinformation poses a serious challenge to open societies, and the coronavirus pandemic has shown just how dangerous online falsehoods and conspiracy theories can be,” he said. “But while combating online disinformation is a legitimate objective in general, handing governments and state-controlled regulators the power to decide what information is true and what is false is a dangerously wrong path.

“This is especially the case when this power has no expiration date, as is the case with many of the ‘fake news’ measures introduced under the pandemic. In the wrong hands, like openly authoritarian states, these ‘fake news’ laws are an obvious tool of repression. But even in the ‘right’ hands there is no such thing as good state censorship.”

He added: “In many states across the world, governments have been using “fake news” as a rhetorical tool to weaken public trust in media. This new incorporation of fake news into law takes this further, contributing to creeping digital authoritarianism and damaging the ability of the press to report freely – which as we’ve seen recently is essential for keeping citizens informed and holding governments to account for their management of the pandemic.”

New tool in the arsenal

As feared, in the early stages of the pandemic some governments took little time putting these laws to use against the press.

Perhaps the most forceful application came in Russia, where under the new law, media outlets found to have deliberately spread “false information” about serious matters of public safety such as Covid-19 could face fines of up to €117,000. Authorities also gained the power to block websites that do not meet requests to remove “inaccurate” information and censor those who show “blatant disrespect” for the state online. Within weeks, the country’s media regulatory agency was beginning to use the newest rules to block, censor and fine online media reporting critically on the Covid-19 situation.

Galina Arapova, director and senior media lawyer at the Mass Media Defence Centre in Russia, told IPI that among those targeted were journalists working for independent outlets long targeted by the government, such as Echo of Moscow radio station and Radio Free Europe, including journalist Tatyana Voltskaya. “In the early stages of the pandemic Russian authorities were enthusiastic about opening cases in an attempt to suppress critical reporting as a way to supress dissent more widely,” she said. “But the law has also been worded so vaguely that it can be used against journalists in the future. In that sense, it’s really the ace in the deck for the Russian government.”

Governments in former Soviet states in Central Asia and the Caucasus soon followed suit. In March, the national parliament of Azerbaijan raised concerns over increased censorship in an already suffocating media landscape when it amended the law on information to allow authorities to prosecute the owners of online media for publishing any “inaccurate” or “dangerous” content on almost any subject, according to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

The domino effect continued to Uzbekistan in early April when the government passed amendments criminalizing the spread of “false information” about the virus with two years of correctional labour. Those found guilty publishing “fake news” in the media with the “aim of creating panic” meanwhile face up to three years in jail and heavy fines, under the temporary rules.

Tajikistan followed in July after President Emomali Rahmon signed amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses that make it illegal to disseminate “inaccurate” and “untruthful” information about the COVID-19 pandemic in the media, internet and social media. Media outlets could be fined (€800-1,100). According to reports, the law was used to target civil society groups and to cover-up the scale of Tajikistan’s coronavirus outbreak.

Restrictive webs of legislation widen

In Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines, police used special powers granted during the state of emergency to file a criminal complaint against journalists Mario Batuigas, owner of the Latigo News TV news portal and Amor Virata, an independent reporter, for allegedly spreading “fake” reports on a Covid-19 case. The decree has since expired. Similar temporary powers in Thailand granted the Prime Minister the ability to shut down media outlets accused of spreading “fake news”.

In Cambodia, where the government led by Hun Sen has all but eradicated independent print media in the last four years, a new “fake news” law complemented an already restrictive web of legislation by granting vast new powers to monitor communications and censor the media.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen speaks about coronavirus prevention measures, 07 April 2020. EPA-EFE/KITH SEREY

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen speaks about coronavirus prevention measures, 07 April 2020. EPA-EFE/KITH SEREY

In April, neighbouring Vietnam passed a new law which for the first time gave authorities the power to fine those deemed of spreading “fake news” on social media, worsening an already restrictive legal landscape for media. The government stressed the law would help tackle both “falsehoods” related to the pandemic and wider forms of misinformation.

In the Middle East, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) announced heavy fines for people sharing medical information that contradicted official statements. The government made the health ministry and other state health institutions responsible for distributing “true” health information and guidelines to the nation.

In March, Jordanian King Abdullah approved an emergency “defence law” which handed the Prime Minister sweeping powers to “deal firmly” with anyone who spreads “rumours, fabrications and false news that sows panic” about Covid-19. Human Rights Watch said the law did not appear to have time limits and allowed the government powers to censor and shut down any outlet without justification.

Catherine Anite, a lawyer and Executive Director of the Freedom of Expression Hub, told IPI that such laws were leading to journalists and other critical voices facing criminal charges for reporting the pandemic. “This has led to unnecessary gagging and online censorship, denying the public of their right to know. These laws are inimical to democracy and serve no legitimate purpose besides stifling dissent, debate and punishing valid criticism,” she explained.

!function(e,i,n,s){var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”);

——————————–

Trend spreads further

In Africa, the Algerian government approved a sweeping bill in mid-April amending the country’s penal code criminalizing the spreading of “false news” that threatened the security and stability of the country or undermined “national unity”.

In Bolivian interim President Jeanine Añez Chávez signing a vaguely defined decree in May which imposed a maximum jail sentence of ten years for anyone disseminating “any kind of information… that puts at risk, affects public health, or generates uncertainty among the population”. The restrictions on freedom of expression were repealed on May 15 after criticism from journalistic organizations and international pressure.

In March the government of the north-eastern state of Paraíba in Brazil also introduced fines of up to €1770 for anyone sharing “false news” about the coronavirus or any other pandemic. In April the Governor of Puerto Rico also approved a new emergency law making it illegal for media outlets or social media accounts to share “false information” about the government’s Covid-19 emergency measures.

Europe was not immune. While states such as Romania and the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina had “fake news” laws vetoed or backtracked after pressure from the European Union and OSCE, Hungary pressed ahead in the face of staunch criticism and in late March passed amendments criminalizing the spread of misinformation deemed to undermine the authorities’ fight against the Covid-19 virus with fines and up to five years in prison. The ruling FIDESZ party and its supporters in the media have long used accusations of “fake news” to smear critical journalists.

Agnes Urban, head of the Mertek Media Monitor think-tank in Hungary, said that research had shown that the legislation was having a clear “chilling effect” on newsrooms. “The most obvious effect was the wariness of the potential sources – journalists could hardly find sources in the health care system or education system who were willing to talk. There is a definite fear among ordinary people from the consequences of leaking,” she said. An IPI report also found the new law was leading to self-censorship among journalists.

——————————–

International concern

Though some of these decrees expired when states of emergency were lifted, others are now cemented into the criminal code. In these states, the long-term effects such legislation on media freedom have many international organizations concerned.

“While it is understandable that governments are trying to prevent the spreading of incorrect information about the pandemic, fake news laws are not the way to do it”, Nani Jansen Reventlow, founding director of Digital Freedom Fund and a human rights lawyer specialises in freedom of expression, told IPI.

“In addition to having a chilling effect on those covering issues related to Covid-19, which is vital public interest information, fake news and ‘misinformation’ legislation is often used to crack down on any reporting the authorities might dislike. This can include reporting on their own handling of this public health crisis, on which the public has a right to know.”

A recent report by UNESCO has drawn similar conclusions. It found there was a “grave risk” that “restrictive responses to curtail Covid-19 disinformation could also hurt the role of free and quality journalism” in its ability to counter disinformation – noting that such responses may often violate international standards.

It added: “Heavy handed responses to disinformation that restrict freedom of expression rights, such as ‘fake news’ laws, could actually hobble the work of journalists and others engaged in vital research, investigation and storytelling about the pandemic, and the disinfodemic that helps fuel it.”

Despite the concerns, the string of laws passed during the first wave of Covid-19 has added momentum to legislative efforts that were already underway. In June 2020, for example, a hastily introduced proposals for bill fighting so called “fake news” in Brazil were passed by one of the legislative chambers in parliament.

In the latest case, at the end of September deputies from the party of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega proposed a law that would make spreading “false (or) distorted information, likely to spread anxiety, anguish or fear” on social media punishable by up to four years in prison.

As these types of laws are exported to other parts of the world, they will likely end up in the hands of other illiberal and authoritarian regimes, posing further issues for global press freedom.

——————

“It’s abundantly clear that online disinformation is going to be one of the major social and political challenges of our time”, Griffen said. “But rushing to pass sweeping legislation, especially during times of crisis, is counterproductive. Measures to counter disinformation must be crafted with the input of civil society and journalist groups to ensure that watchdog journalism is not penalized by leaders averse to criticism.”

He concluded: “Ultimately, one of the best ways to counter disinformation is through support for a strong, professional and independent press which can be trusted to act as fact-checkers and sources of reliable information. In the coming years, we are going to have to create new sustainable models in which public-interest journalism can survive and fulfil this important role. Until we do, disinformation will continue to further contaminate the digital sphere and undermine our democracies.”