In a short space of time, the COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped much of the world and posed unprecedented new challenges to journalists and media outlets alike.

In many autocratic countries with already poor records on press freedom, governments have abused emergency measures to crack down further on independent media and tighten control over information.

In democratic states usually more insulated from attacks on the press, the health crisis has created new problems and seriously challenged the ability of journalists to access information and hold power to account.

At the same time, concerns over online misinformation have presented governments both autocratic and democratic new opportunities to ramp up censorship and strengthen surveillance capabilities, further shrinking digital freedoms.

Simultaneously, despite a huge increase in readers and subscribers seeking trustworthy news, many newspapers are also facing a prolonged period of severe economic pressure due to a lack of advertising revenue, while many smaller newspapers face closure.

Globally, the pandemic has accelerated an already worrying decline in media freedom observed over the past year.

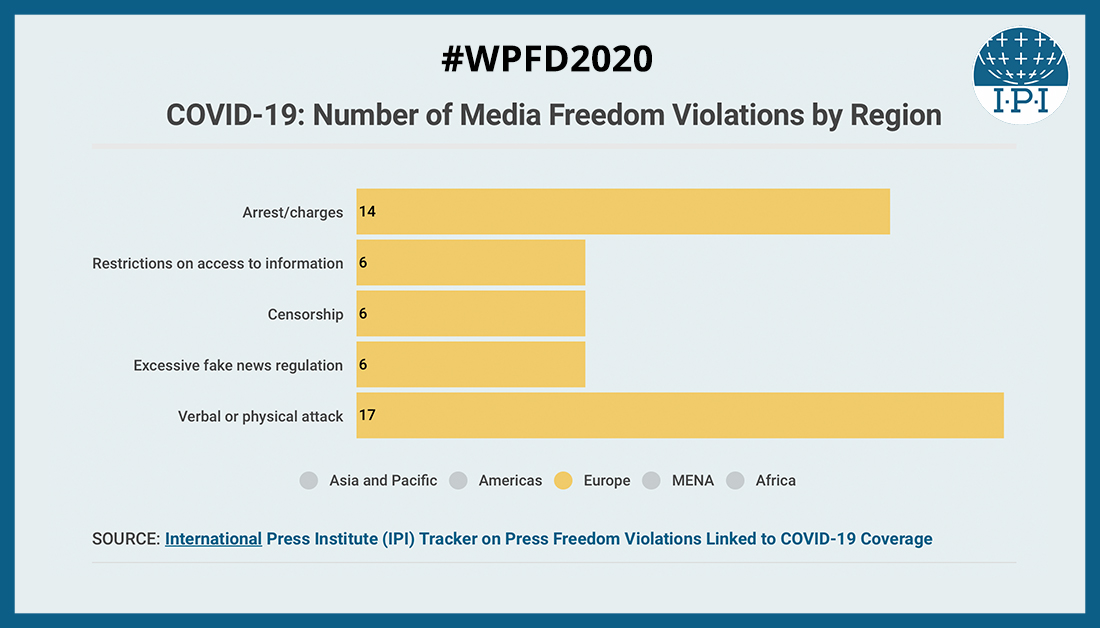

Over the last two and a half months, IPI’s COVID-19 tracker has documented a total of 162 different press freedom violations related to the coronavirus.

Troublingly, almost a third of all violations monitored have involved the arrest, detention or charging of journalists reporting on the pandemic, according to IPI’s data.

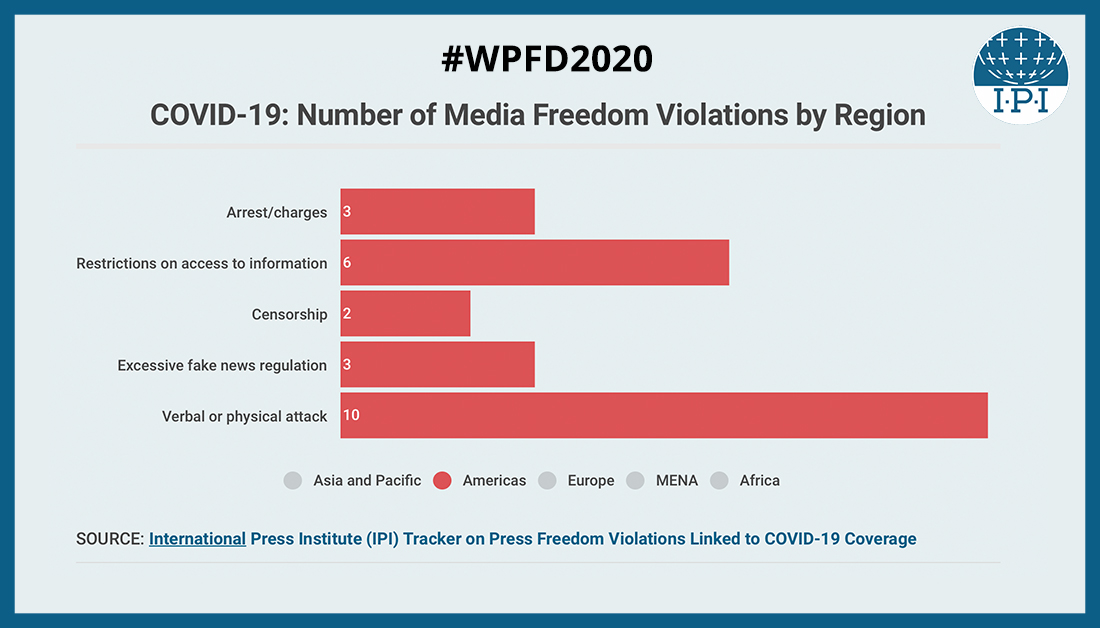

More than 50 individual instances have also been recorded of reporters around the world being threatened, verbally attacked or physically assaulted due to their coronavirus coverage.

Meanwhile, 27 different cases of censorship have been documented, with a further 25 examples of disproportionate restrictions on access to information.

Taken together, said IPI Executive Director Barbara Trionfi, the data illustrates governments’ urge to take advantage of a public health crisis to control the media message, in full disregard of people’s thirst for independent information.

“In covering the COVID-19 pandemic, journalists across the globe have found themselves confronted not only with the risk of contagion, but also with the threat of arrest, beatings or physical assault by security forces or criminal charges due to reporting on the virus. This has created an even more hostile environment for independent media.

“It is crucial that extraordinary restrictions on media imposed during the crisis do not become normalized and outlive the immediate health crisis, especially when it comes to lack of transparency by governments, lack of access by media to decision-makers and any form of surveillance hindering the press.”

She added: “Meanwhile, pressure on media is only likely to get worse with the impending economic crisis, which is hitting small, independent media hardest. In many countries, where these outlets are the only source of impartial news, additional economic strains will only deepen government’s control over the press and lead to less checks and balances on their future attacks on the media.”

New opportunities for media control

One of the most apparent trends observed, Trionfi said, was how many governments had abused the pandemic to strengthen their grip over the media through excessive regulations.

A clear example here has been a proliferation in the number of states adopting or unleashing laws against disinformation or “fake news” that can be easily abused to stifle criticism. So far, IPI had documented 16 cases of such laws either being passed with disproportionate penalties or used to take down content about the virus online.

While some of these laws are sincere but ill-conceived, others appear to deliberately strengthen authoritarian regimes’ arsenal against the press.

In Russia, the Putin government has weaponized concerns over “fake news” and misinformation to ramp up its censorship of critical outlets. In Hungary, an EU member state, the government has handed Prime Minister Victor Orbán indefinite emergency powers to rule by decree and criminalized the spread of “false” or “distorted” information for the first time, marking another step toward total information control.

While some states such as the Philippines have banned “false information” specifically about the virus, others like Vietnam and Algeria have used the crisis to rush through laws criminalizing misinformation more generally, often with heavy penalties.

Other states have used blunter tools to quash dissenting reports on the government’s response to the pandemic. In Turkey, authorities have detained at least six journalists due to their reporting on the virus, while in Azerbaijan the government has used the crisis as a pretext to throw three critical journalists in jail. In Egypt, where more than 60 journalists are currently behind bars, the government has blocked opposition news websites and revoked press credentials.

With the risk of infection high in these overcrowded prisons, IPI has called on authorities in Cairo and Ankara to release all journalists during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, an increase in the use of targeted surveillance technology to track people infected with the disease in more than a dozen states worldwide has also had a chilling effect on journalists and posed new threats to source protection.

Regional trends emerge

Different trends have been observed in different regions of the world.

In the Americas, leaders such as Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro have used the pandemic as an excuse to further insult critical journalists, discredit outlets and undermine trust in media.

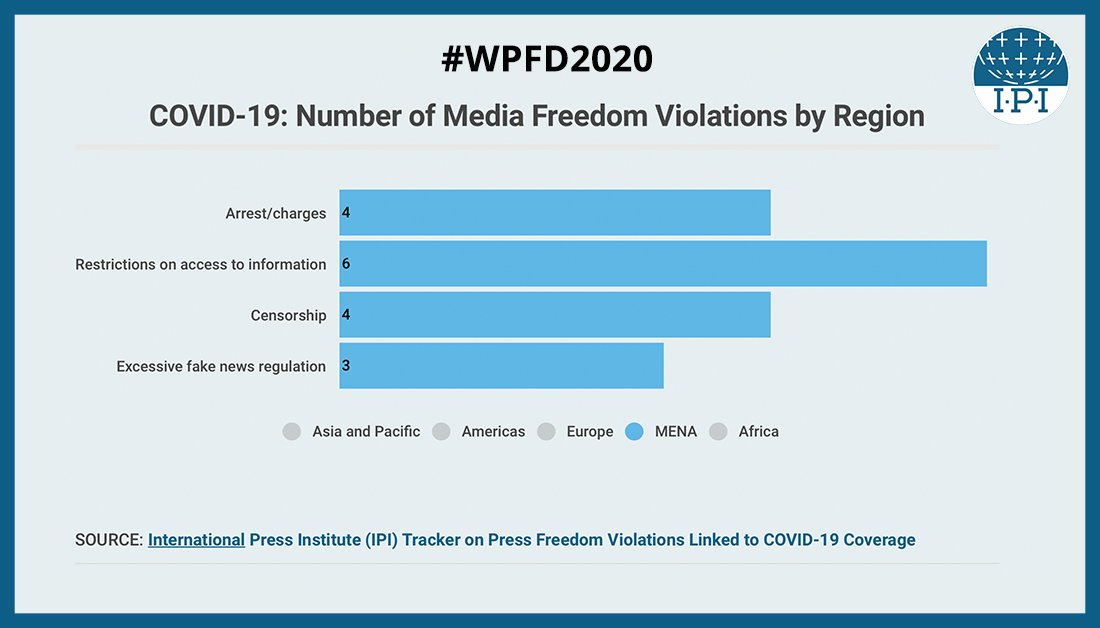

In the Middle East, where the space for dissent was already highly restricted, governments in four different states suspended the printing and distribution of all newspapers. In Jordan, security forces arrested the owner and news director of a TV channel which aired interviews with frustrated residents criticizing the government.

Others have used more targeted measures to shield themselves from criticism. In Iraq, authorities banned Reuters for three months because it reported that the number of coronavirus cases was higher than the government admitted. In Iran, meanwhile, sweeping lockdown measures have been accompanied by police summons and censorship of individual journalists reporting on the virus.

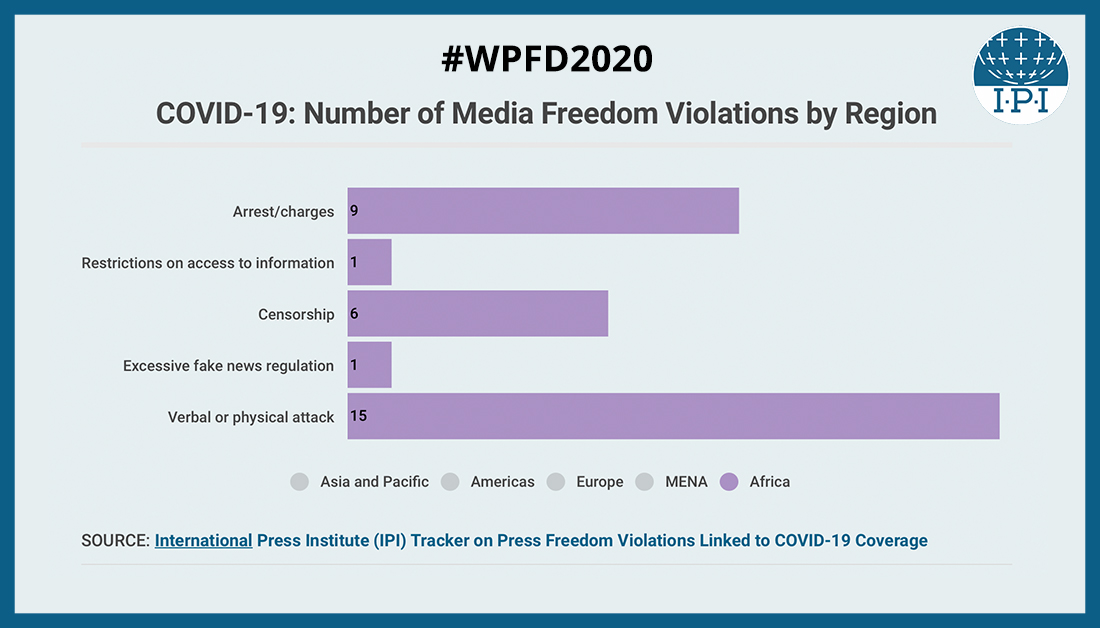

In Africa, where the virus struck late, IPI has documented 32 different media freedom violations.

Uganda, Somalia and Zimbabwe have between them already recorded 16 instances of journalists either being beaten or detained by authorities in connection with their reporting on the virus. As IPI research has shown, many of these incidents have involved security forces heavy-handedly enforcing quarantine measures.

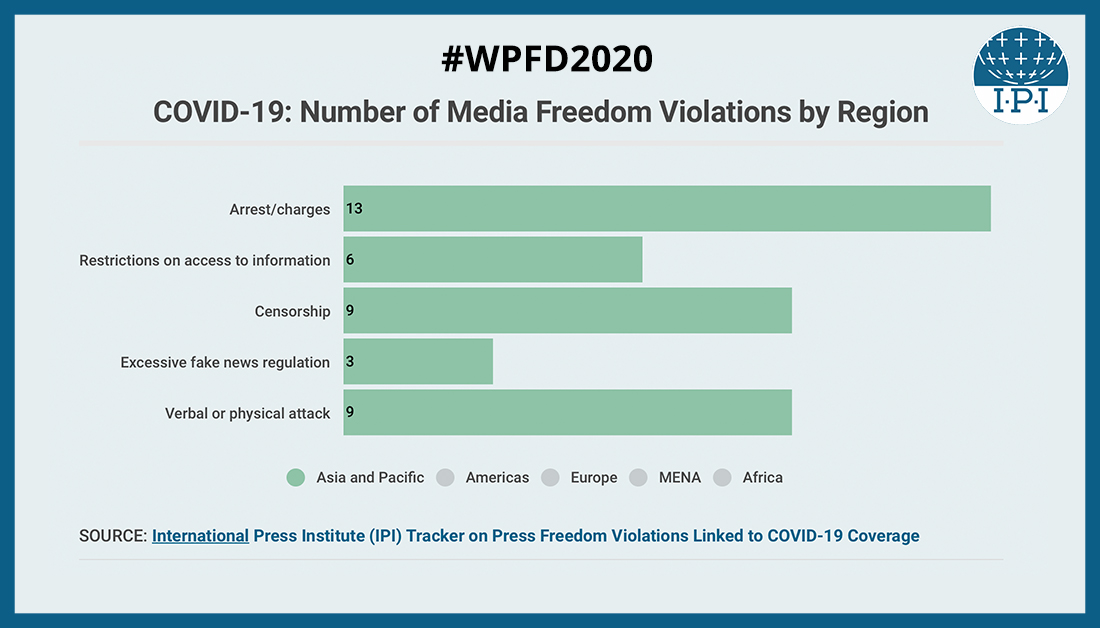

Further East, numerous Asian states have used newly created “anti-fake news” laws to ramp up internet censorship in their heavily digital news environments.

Cambodia has handed Prime Minister Hun Sen sweeping emergency powers to surveil telecommunications and control social media, while Myanmar blocked multiple news websites that were caught up in its dragnet approach to tackling online misinformation.

In already heavily censored China, the Communist Party further ramped up policing of the internet, suppressed “unofficial” media reporting and persecuted citizen journalists reporting on social media about the reality of the situation.

However, in other populous states like India, where IPI has so far documented the most individual violations, overzealous police enforcing lockdown measures have beaten or unjustly detained eight media professionals, contributing to a deterioration in media freedom.

In Europe, journalists have been attacked by members of the public with alarming frequency. Italy, one of the countries hit hardest by the virus, has seen at least three instances of physical or serious verbal attacks on journalists and TV crews. Journalists reporting on virus-related issues have also required medical treatment after assaults in Ukraine and Croatia.

While the vast majority of the arrests in Europe were documented in Turkey, Russia and Azerbaijan, journalists have also been wrongly detained in Serbia and Kosovo. States such as Romania have handed authorities powers to remove or close websites that spread “fake news” about the virus, with no opportunity to appeal.

As a new report by the partner organisations to the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists found, the pandemic risks these kinds attacks on press freedom risk becoming normalized.

Positively, several of the disproportionate regulations announced by European governments have since been rolled back, either through democratic checks or strong pressure from media and civil society.

Killings of journalists continue

Though the world’s attention has been consumed by the coronavirus, the past twelve months have proven another deadly year for journalists.

Since May 2019, 53 journalists have been killed in connection with their work, according to IPI’s data.

Thirty-two of those were murdered, with most of these targeted killings carried out by armed groups, state security forces, or organized crime.

Latin America continues to be the worst region in the world for journalists, where 20 journalists lost their lives in targeted attacks, with 10 in Mexico alone.

Armed conflicts and civil unrests claimed the lives of 14 journalists. Of these seven were killed in Syria and three were killed in Afghanistan, Chad and Yemen respectively, while covering armed conflicts. Two journalists were died in Iraq covering the civil unrest. A further six were killed while on assignment.

Unfortunately, investigations into targeted killings remain slow and deficient. As a result, no arrests have been made in many of these cases.

Positively, progress has been made in the trial of those suspected of murdering Slovak investigative reporter Jan Kuciak.

Since 1997, IPI’s Death Watch has tallied journalists deliberately targeted because of their profession and those who lost their lives while covering conflict or while on assignment.