“We sharpen the idea, but the beginning of the message usually comes from the local journalist”, says Paritta Wangkiat, editor of Mekong Eye. Amid mounting environmental crises and crackdowns on press freedom in the Mekong region, Paritta’s words capture the essence of a platform which has evolved from an archive of news to an independent environmental outlet amplifying the voices of local journalists—those closest to the communities they cover.

The challenge that Mekong Eye is facing is familiar to many non-profit donor-funded media organizations: how to create and sustain revenue? How to avoid grant dependency? And what are the ways to break out of limiting audience funnels? The Mekong Eye team, encompassing editors and journalists from Cambodia, Viet Nam, and Myanmar, shared their experiences with IPI’s Media Innovation team.

Mekong Eye’s mission and impact

Mekong Eye was launched in 2015, originally as part of a project to build the capacity of journalists for macro-level reporting in the region. The idea was to create a site that would archive journalistic content and investigations on the transboundary Mekong environment and climate issues, especially across the Greater Mekong Subregion in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The publication’s coverage is vast. The Greater Mekong Subregion includes the Mekong River, the longest river in Southeast Asia, abundant with natural and human diversity. Climate change is a present reality in the region, directly affecting the lives of millions dependent on the river’s resources. The communities face conflict, displacement, agricultural overproduction, and threats to biodiversity, often fueled by government corruption and foreign development. Investigations into such stories are not only difficult to execute but also dangerous.

Prompted by this context, Mekong Eye adapted its strategy to better serve the needs of the region. In addition to its original mission, the team set out to produce original content from local journalists, working with both newsrooms and freelance reporters. In 2020, they pivoted to becoming a fully fledged news site, producing around one in-depth study a week, still under the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network project.

To engage audiences, Mekong Eye has been experimenting with diverse formats, like “Eye Original”, showcasing original stories contributed by local journalists, partners, and grantees of the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network; “In Their Eyes”, focusing on the voices of local experts and communities; “Eye on Solutions”, highlighting innovative solutions and ideas from diverse voices; and “Special Reports”, a series of longer-form, multimedia investigations. The content is published on the website and featured in a weekly newsletter of curated content.

Recognizing the impact of local reporting, Mekong Eye provides opportunities for local journalists to improve their reporting skills and a platform to share local perspectives with audiences outside their countries. Local journalists can pitch ideas for the story fund and mentorship, which gives them the necessary financial support and technical guidance from the editorial team and the wider network. The team consists of 3 main editors from Viet Nam, Myanmar and Thailand, who mostly work with freelancers from other newsrooms in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam.

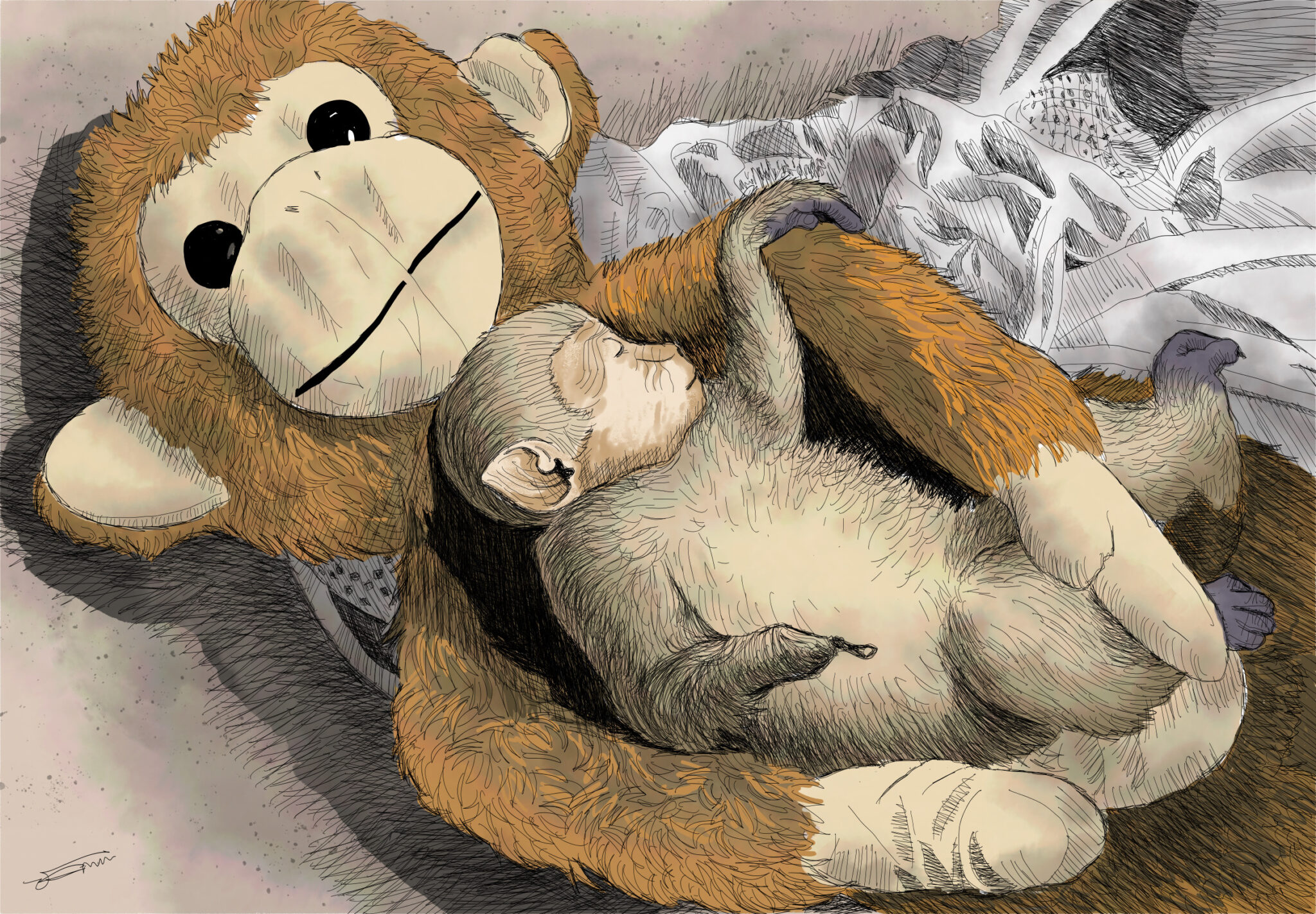

Shwe Ky, an infant macaque caught in Kachin State, was sold to a white-collar worker in Yangon. He was very fatigued when arriving at the hands of the buyer who arranged the wild animal’s bed on a monkey doll. ILLUSTRATION: Paritta Wangkiat for “Endangered wild monkeys for sale online in Myanmar”, by Mekong Eye. Social media campaign has leveraged public outcry and a campaign against the sale of wild langurs and monkeys as pets #OurMekongOurSay #IamLangur.

Safeguarding and promoting voices on the ground

“Many local journalists experience leaks and threats after publishing their stories in local outlets… having an English language outlet operating outside their countries is kind of the solution,” says Paritta.

Despite international funding and regional reach, local journalism is central to Mekong Eye’s mission. The editor at Mekong Eye says there are still many media outlets that are withstanding governmental propaganda and additional grant support is critical to staying afloat.

“I know in Viet Nam there are many, many talented and dedicated journalists, but their English is limited so they could not have enough opportunity to bring their work, which provide intimate insights into the country, to international audiences”, says Vo Kieu Bao Uyen, a journalist from Viet Nam.

Specifically, journalists working in local outlets can publish their stories both on the Mekong Eye site and in their publications in local languages, which can reach their readers on the ground. The team offers translation support and publishes original content in English, Burmese, Thai and Vietnamese. For example, Uyen, a journalist in Viet Nam, explains that she writes the original story in English and then with the help of local editors and AI tools, she translates it to Vietnamese in a way that caters to Vietnamese audiences. In contrast to other foreign independent media in the region, Mekong Eye’s local editors tend to give space for nuance and understanding of possible risks associated with covering a specific story, due to their own experience and connection to the area. “Thanks to Mekong Eye’s local editors, my investigative projects across borders are avoidable from being covered parachute-style or taken out of context for nations related to the project”, said Uyen.

“Without them, it is tough for me to survive as a freelance journalist in Viet Nam”, she added.

Cambodian journalist Meng Kroypunlok, writing in Khmer, reflects on the experience of working with Mekong Eye, after the closure of the Voice of Democracy (VOD) in 2023 – one of the few prominent independent outlets in the country. Ever since, press freedom in Cambodia has been declining dramatically, leaving environmental journalists like Kroypunlok with virtually no prospects of working on local stories with local outlets and in local languages. Mekong Eye became one of the few platforms open to in-depth environmental stories that get attention.

“A lot of people struggle, a lot of people participate… under the military regime… and I need information, but I didn’t know where to find it at that time.”, explains Poe Phyu Zin, a journalist from Myanmar.

Similarly, in Myanmar, environmental issues rarely make it into the news. The state of constant crisis and conflict has been detrimental to local journalists. Passionate about the environment and gender equality, Poe Phyu Zin’s journalistic career was ignited by the existential lack of information back in 2007, at the time of the Saffron Revolution. “A lot of people struggle, a lot of people participate… under the military regime… and I need information, but I didn’t know where to find it at that time.” Born in Rakhine State, she witnessed the tragedies of armed struggle and how important it was to represent everyday people, most affected in the crossfire.

Years later, having worked in several countries, exploring long-form human-interest stories for outlets like Al Jazeera Arabic, BBC-World Service, and KBR 68’s Asia Calling Radio, Phyu Zin’s BBC radio documentary won the Asia Broadcast Union Award in 2021, forcing her to move from Myanmar to Thailand, where she started working with Mekong Eye.

Strengthening cross-border solidarities

Cross-border exchange, workshops and training on specific environmental issues and holistic support was a unique offering by Mekong Eye. “Local journalist networks of the other five Mekong countries can pursue collaborative projects or even just consult that network. People know about each other and they are really supportive of each other. So Vietnamese journalists that I’ve worked with, definitely have consulted with other journalists from Laos, Cambodia and Thailand on the situation that are cross border.”, says Mekong Eye editor.

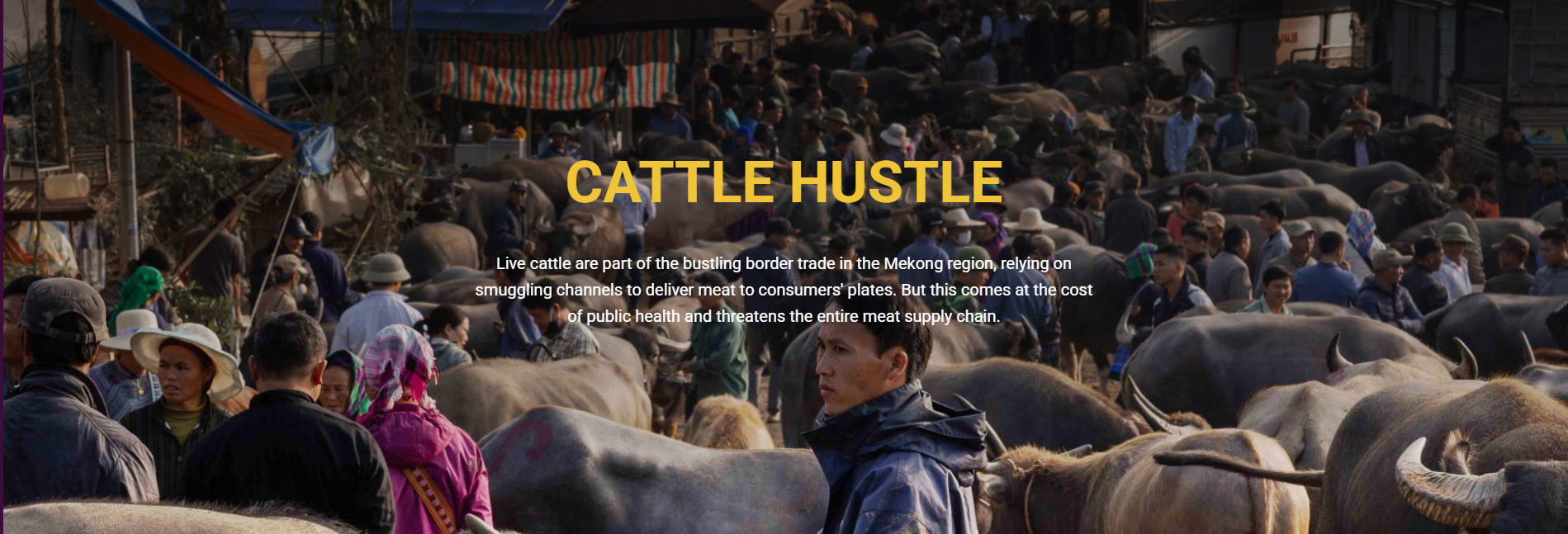

Cattle Hustle – Mekong Eye Special Report, supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, this collaborative report brings together seven journalists and photojournalists from six media outlets in Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, and Viet Nam to investigate the health and economic impacts of illegal cattle trade in the region.

The support also extends to citizen journalists, who help carry out many of the investigations in Myanmar, which is hard to access without a foreign media badge and risk assessment. Despite limited resources, Mekong Eye also encourages journalists to share information on how to safely report in the area. “When I told them that I needed to coordinate with the citizen journalist and I wanted to pay them because they are normally unpaid”, Phyu Zin recalls, the Mekong Eye team agreed to include them in the budget sheets, unlike other media organizations that Phyu Zin had previously worked with.

Escaping grant cycles

Like many donor-funded media organizations, Mekong Eye struggles to break free from the non-profit news ecosystem. As Paritta points out, donor funding is always subject to changing priorities in the development landscape, with more funding being allocated to other world crises, such as conflicts in Western Asia.

Their second editor, explained that revenue instability “creates a challenge for us in expanding the team… We are in the comfort zone, but at the same time, we have to keep our skillset small.”

Consequently, Mekong Eye seeks to diversify its readership—which now consists primarily of professionals in development fields, UN workers, and researchers, and leverage the broader audience’s support as a critical component of long-term sustainability.

The team launched a user survey in 2024 and found ideas for generating revenues, including donations, which 90% of the survey respondents say they are willing to pay in different amounts. They also express their interest in supporting some services, including event organizing, sponsor content, and data consulting. The team is working on the donation channel and considering which options can be implemented. In addition to this, Mekong Eye is consulting with experts on the possibilities of using their social media platforms for revenue generation.

I will say they kind of have power (their main readership) on decision-making, designing, who gets the grants, and which community is going to have support, right? So I think we definitely need to keep this audience, but at the same time, we do really need to expand the audience to the local audience too. I mean not just those speaking English, but also non-English speaking… They are like the foundation of our survival in the future… They (English-speaking readers) come and go, but the local people stay,” says Paritta.

These strategic initiatives will help ensure the platform’s continued success in amplifying marginalised stories and critical civic issues while fostering a sustainable future for Mekong Eye, its team and its local network.

Whatever comes next, Mekong Eye will strive to preserve its collaborative model with local journalists. “I heard a lot of good feedback from local journalists that they feel really uplifted”, says Paritta, reflecting on the impact of the organisation. That they are able to do the things they want to do”. Ultimately, this sense of empowerment strengthens the communities they serve, creating a ripple effect of positive change.

Follow Mekong Eye

- Location: Mekong Region

- Website: mekongeye.com

- Instagram: @mekongeye

- Facebook: Mekong Eye

This story is part of IPI’s Local Journalism Project. The publication of these case studies – part of IPI’s wider work mapping, networking and supporting quality innovative media serving local communities – is supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation.