In voting last month to repeal their country’s centuries-old blasphemy law, Danish lawmakers joined a growing trend in Europe toward securing free speech on matters related to religion.

A comprehensive IPI study on criminal defamation and insult laws published in March by the Representative on Freedom of the Media of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) highlighted that the Netherlands (2014), Iceland (2015), Norway (2015), Malta (2016) and France (2017) had all abolished blasphemy laws in recent years.

But the study also revealed the extent to which blasphemy and related “religious insult” laws continue to exist in the OSCE region, which covers 57 states in Europe and Central Asia, as well as the United States and Canada.

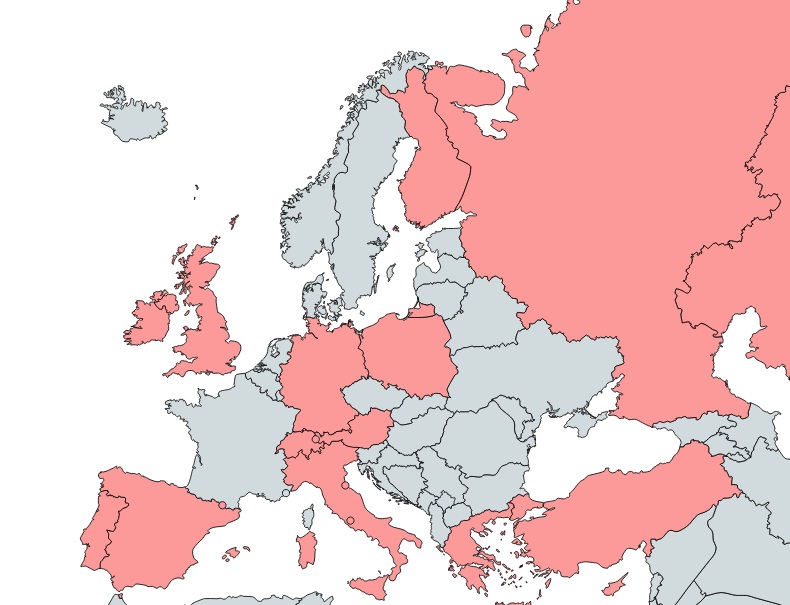

Updated to account for the recent legal changes in Denmark, the study concluded that 19 OSCE participating states maintain blasphemy or religious insult laws: Andorra, Austria, Canada, Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Liechtenstein, Poland, Portugal, the Russian Federation, San Marino, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom (Northern Ireland and Scotland) and the Vatican City. This list excluded countries like Belgium and Luxembourg, which provide narrower provisions for insulting the objects of a religion in places of worship or public ceremonies.

Map: OSCE member states with blasphemy and religious insult laws. Not shown: Canada.

Categorising provisions as blasphemy and or religious insult can be complex, given that legal terminology differs from state to state and the lines among blasphemy, religious insult, group defamation and incitement to hatred are frequently blurred. The IPI study focused on provisions that aim to protect particular belief systems and their practices, dogma, deities and objects of worship as well as the feelings of their followers.

The list includes, for example, laws in Finland and Greece, which continue to criminally sanction – under threat of imprisonment – “blaspheming against God” and “showing disrespect to the divine”, respectively. Art. 188 of the Austrian Criminal Code prohibits “ridiculing or denigrating a religious doctrine, a religious custom, or a person or object that constitutes an object of worship” under penalty of up to six months in prison.

In other cases, the primary focus appears to be protecting the “feelings” of religious believers, although religious doctrines and objects may still be granted protection per se. Consider, for example, Art. 525 of the Spanish Criminal Code, which criminalises “offending the feeling of members of religious groups or publicly disparaging their dogmas, beliefs rites or ceremonies”. In a similar vein, Art. 261 of the Swiss Criminal Code bans “publicly and maliciously insulting or mocking the religious convictions of others, especially the belief in God; dishonouring objects of religious veneration”.

While the IPI study did not look systematically at the application of blasphemy and religious insult laws, it is clear that prosecutions and convictions continue to occur. In 2014, a 27-year-old Facebook user in Greece was given a 10-month suspended prison sentence for satirising a deceased Greek Orthodox monk. In 2017, Irish police investigated the English author Stephen Fry over a television interview in which Fry said he could not respect “a capricious, mean-minded, stupid God who creates a world … full of injustice”. A German court in 2016 fined a former schoolteacher for driving a car decorated with stickers derisive of Christianity, which prosecutors claimed threatened “public peace”.

There are signs that the movement to repeal blasphemy laws will continue in the OSCE region. The Canadian Parliament is currently considering a bill that would repeal the offence of blasphemous libel, which carries a potential prison term of up to two years. In Greece, Maria Giannikakis, general secretary for transparency and human rights in the Greek Justice Ministry, told IPI in an interview in April that the government would pursue the abolition of Greece’s blasphemy law, which Giannikakis said no longer had a place in Greek society. Irish lawmakers are continuing to push for a referendum to repeal the country’s constitutionally backed blasphemy provision.

International standards

International human rights bodies generally oppose the existence of blasphemy laws. The U.N. Human Rights Committee, which monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which all OSCE states save Vatican City are a party, has stated that “prohibitions on displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws” are incompatible with international human rights norms.

Similarly, the free expression rapporteurs of the OSCE, the U.N., the Organization of American States and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights have rejected the concept of “defamation of religions” and have emphasised that laws restricting free expression should “never be used to protect particular institutions, or abstract notions, concepts or beliefs, including religious ones”.

The Rabat Plan of Action, a series of expert recommendations on combating hate speech developed by the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights in 2012, concluded: “At the national level, blasphemy laws are counter-productive, since they may result in the de facto censure of all inter-religious/belief and intra-religious/belief dialogue, debate, and also criticism, most of which could be constructive, healthy and needed.”

Global impact

Critics of calls to repeal blasphemy laws have pointed to a need to protect minorities or “maintain peace” among religious communities. But most OSCE member states, including all EU states, have separate laws against incitement to hate, discrimination and violence that are better tailored to protect religious minorities than blasphemy provisions, which have historically served the interests of majority belief systems.

But perhaps the most urgent cause for repealing blasphemy laws in Europe and North America is the signal these laws send amid severe state repression and violence attacks against those accused of offending religious practice in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.

In June, a Pakistani anti-terror court sentenced a Facebook user to death over comments critical of the Prophet Mohammad. Months earlier, a mob in northern Pakistan murdered a young university student over allegedly blasphemous comments on Facebook. Saudi Arabian blogger Raif Badawi remains behind bars after being sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes in 2014 for “insulting” Islam in an online forum.

IPI and other groups have previously argued that European states with blasphemy provisions still on the books open themselves up to accusations of hypocrisy when defending free expression globally, ultimately weakening calls to free critics of conscience.