Since Tanzanian President John Magufuli took office in late 2015, the weekly newspaper Mawio has been forcibly shut down not just once, but twice.

Most recently, the paper was banned after it published an article in June 2017 detailing problems in Tanzania’s mining industry and attaching pictures of two former presidents to the story. Using administrative powers, the government suspended Mawio for two years on grounds of “national security and public safety”. The move came just months after the country’s High Court had lifted a previous ban, handed down in January 2016.

Simon Mkina, Mawio’s editor and the president of the Tanzania Journalists Alliance, told the International Press Institute (IPI) that his paper has again appealed to the High Court, which has not yet studied the case.

“The government should leave the media to do their work because they are contributing to the development of this country”, Mkina said.

Mawio is far from alone in its experience of censorship in Tanzania.

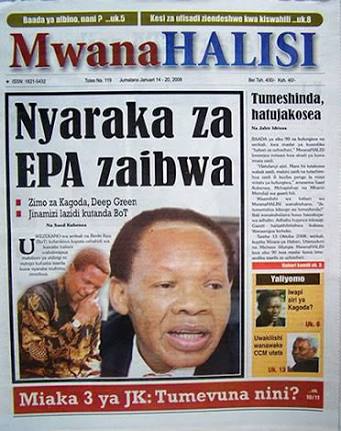

Last September, the Swahili-language weekly MwanaHALISI also published a story that upset the government. The article called for prayers for the opposition leader Tundu Lissu, who had recently been shot. The headline of the article asked whom Tanzanians should “pray for”, the president or Tundu Lissu.

The government apparently interpreted the headline as an insult to Magufuli and suspended the paper for two years for “sedition”.

“The reasons for the ban were weak according to the law”, Jabir Idrissa, MwanaHALISI’s editor, told IPI. “We were clamped down on because we raised opposition voices. If you want to survive, you have to report what the government wants.”

Idrissa said the weekly has been able to continue publishing separately online but forced to operate without subscriber revenues.

In addition to having their papers banned, Mkina and Idrissa have also been charged with sedition and threatening national security because of an article that Idrissa wrote for Mawio in 2016. The court case is still ongoing.

Disappearances, arrests shake media landscape

Press freedom in Tanzania has drifted into an unprecedented crisis under Magufuli’s regime. According to the Tanzania Editors Forum (TEF), at least five newspapers and two radio stations have been suspended for periods ranging from three to 36 months on pretexts including “false information”, “sedition” and “threatening national security”. One paper decided to suspend publication itself after publishing a story it feared might irritate officials.

There have also been more violent incidences of harassment.

In March 2017, Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner Paul Makonda entered the headquarters of Clouds Media with six armed men, reportedly to pressure the staff to air a video undermining a popular local pastor critical of the commissioner. A probe team by then-Minister of Information Nape Nnauye concluded that Makonda had broken the law. What followed was indicative: Nnauye was sacked by President Magufuli, and his replacement, incumbent Minister Harrison Mwakyembe, dismissed the probe team’s recommendations, which included having the commissioner apologize to the media outlet.

Another alarming incident took place in November 2017 when journalist Azory Gwanda was reported missing by his wife in Kibiti district, south of Dar es Salaam. He has not been seen since, dead or alive. Before his disappearance, Gwanda had reported on the high murder rate in the district. Tanzanian security authorities have claimed the matter is still under investigation.

Just last week, two journalists were reportedly attacked and beaten by police officers in separate incidents in Tanzania. Sillas Mbise, a Wapo Radio sports journalist, was attacked at a football match in Dar es Salaam, while Tanzania Daima journalist Sitta Tuma was beaten after taking photographs at a political rally in Mara Region.

The Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition has recorded several other attacks on journalists over the past few years, including arbitrary arrests and detentions of journalists because of their reporting on politics, the police or demonstrations.

Deodatus Balile, the TEF’s acting chairman, told IPI that these recent incidents had resulted in growing self-censorship among journalists.

“Due to the number of threats, journalists start to censor themselves”, Balile said.

New media laws used to curtail press freedom

The crackdown on press freedom in Tanzania is being facilitated by a legal framework that has become increasingly unfriendly under Magufuli’s regime.

Tanzania’s constitution guarantees freedom of speech but does not explicitly mention press freedom. Journalists say this distinction has allowed the country’s authorities to enact laws that curtail press freedom on the pretext of national security and the “public interest”. One of the most troubling examples is the Media Services Act, which was signed by Magufuli in November 2016 to replace the Newspaper Act of 1976.

The Media Services Act concentrates power over media in the hands of the government. The minister of information is responsible for licensing print media annually and is able to prohibit importation of publications contrary to the public interest and order private media houses to report on issues “of national importance”. The law does not define “public interest” or “national importance”, leaving wide room for interpretation.

Under the new law, the government now also holds de facto control over two regulatory bodies: the Journalists Accreditation Board and the Independent Media Council, which is responsible for upholding ethical and professional standards. All practising journalists in Tanzania must obtain Board accreditation and be members of the Media Council. Both bodies are officially independent, but their board members are appointed by and are accountable to the minister of information.

IPI previously expressed concern over the Media Services Act in 2016 for its potential threat to press freedom and its failure to meet international standards. On that occasion, IPI also urged the Tanzanian Parliament to abolish licensing requirements for journalists, newspapers, social media and broadcast media, as well as to repeal criminal defamation laws.

The TEF and other media stakeholders have also raised concerns over online media regulations introduced in March 2018. The Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations require all bloggers as well as online radio and television streaming services to apply for a license and to pay a fee up to $900. In reality, however, the cost is even higher because applicants must first establish a company in order to apply for a license. Per capita income in Tanzania was slightly below $900 a year in 2016.

These regulations also give a quasi-independent government body, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority, the ability to revoke a permit if a site publishes content that “causes annoyance” or leads to “public disorder”, without providing any right to appeal or request judicial review of takedown orders. Anonymous use of the Internet is now essentially prohibited as well. Failure to comply with the regulations may lead to heavy fines and to imprisonment for a minimum period of 12 months.

Media stakeholders fear that the regulations will further restrict freedom of expression, citizens’ right to privacy and the work of whistleblowers and investigative journalists. After the regulations came into force, several blogs as well as a popular social media platform called JamiiForums went dark as they failed to register according to the new rules. (Some of the sites were later reinstated.)

The media’s fear is based in part on past experience. Concerns raised three years ago over the Cybercrimes Act, which was passed under President Jakaya Kikwete in 2015 and foresees draconian fines and lengthy prison sentences for publishing false or “misleading information”. Examples of cases filed under the law’s nebulous provisions have proven those fears justified, Tanzanian journalists say.

Growing self-censorship

Deodatus Balile, the acting chairman of the Tanzania Editors Forum, condemned Tanzanian government actions to curtail press freedom in his speech on World Press Freedom Day, May 3, 2018. Photo: TEF

By misusing vague legal terms to curtail the freedom of expression, Magufuli’s government has silenced many journalists and their possible sources, such as politicians and members of civil society, as they are afraid of contradicting laws of which they might not even be aware.

“At times, journalists may find a big story, but they are not digging it out”, Deodatus Balile said. “Journalists with no legal background find themselves in a dilemma.”

The TEF is now looking for ways to provide journalists with legal training to prevent these problems.

A local journalist who wished to remain anonymous agreed that the pressure put on media has made most journalists extremely careful.

“They think two times before airing or publishing something”, the journalist told IPI.

Balile also said that many editors are afraid to hire journalists from papers that have been banned, fearing that such a move may result in the suspension of their own newspapers.

A turn for the worse

Newspaper bans and problematic media laws are not new in Tanzania. MwanaHALISI, for example, was suspended by a previous government back in 2012 as well.

But journalists say the situation now is much worse than in the past due to the Magufuli administration’s aggressive attitude toward the press.

Idrissa described the measures taken by the incumbent government as psychological warfare to silence critical voices.

“Before, it did not always go smoothly but we still did a good job”, Idrissa said.

The draconian Newspaper Act 1976 allowed the police and legal inspectors to raid any newsroom or printing facility. Though these extreme sections were left out of its replacement, the Media Services Act, the press freedom situation has nevertheless worsened.

Idrissa added: “We were enjoying the freedom of expression though the law was so bad.”

Last year Magufuli warned journalists not to take their freedoms too far.

“I would like to tell media owners – be careful, watch it. If you think you have that kind of freedom, it is not to that extent”, Magufuli reportedly stated.

Magufuli has been described as a Trump-like figure: He came to power outside the inner circle of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi party and does not hesitate to stage a show publicly. At first, Magufuli was praised for his anti-corruption measures, but his dictator-like attitude towards press freedom and freedom of expression has raised concerns abroad, in the European Union and the United States for example.

The TEF and local editors have brought up press freedom in discussions with the government, but with little effect.

“On the World Press Freedom Day this year, I said to the minister of information that they have no right to suspend newspapers”, Balile said. “He responded that the law does not give the government that right, but the government can use the so-called residual powers.”

Court rulings fall on deaf ears

Despite the growing pressure, Tanzanian journalists have not given up the fight for a free press.

Publishers of banned newspapers have sought justice from the Tanzanian High Court and the East African Court of Justice. Last month, the High Court overturned the suspension of MwanaHALISI.

“I am relieved that at least we can say that the judiciary is still independent, and justice has been done on our part”, Idrissa said. “We proved once more that we did not do anything wrong.”

But the paper’s future remains uncertain under the prevailing political situation. To continue publishing, MwanaHALISI would have to receive a license from the government.

Idrissa told IPI that everything needed for the registration has been submitted and now they can only sit and wait: The law doesn’t provide a time limit within which the government must announce its decision.

There is reason to be concerned over the speed of the decision. In June, the East African Court of Justice ordered the Tanzanian government to reinstate the weekly Mseto, but the government so far has declined to implement the ruling.

For his part, the Tanzania Journalists Alliance’s Simon Mkina is still waiting for the High Court to review the ban on Mawio – and for the government to implement the court’s previous rulings.

“We are asking for the government to take the rightful actions that court has ordered and reinstitute these newspapers”, he remarked. “The people have the right to know and to contribute to the media.”

Balile, of the Tanzania Editors Forum, was still hopeful that the High Court’s ruling in the MwanaHALISI case might yet have an effect on the president and the government.

“Maybe it sends a strong message that they need to respect the rule of law.”