Just over one year ago, German satirist Jan Böhmermann performed a reading of a vulgar poem about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that would unleash both a debate about the limits of satire and the fury of Turkey’s thin-skinned strongman. Despite German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to grant Erdoğan’s request to allow a case against Böhmermann to go ahead, prosecutors dropped all charges in October.

The case also called attention to a seldom-used provision of German criminal law that punishes insult to foreign heads of state with up to five years in prison and which the German government has since committed to repeal.

A brief post by the International Press Institute (IPI) last year showed that similar provisions existed in a number of EU member states. Now, a new study released last month by the Office of the OSCE Special Representative on Freedom of the Media and conducted by IPI researchers offers more extensive insight.

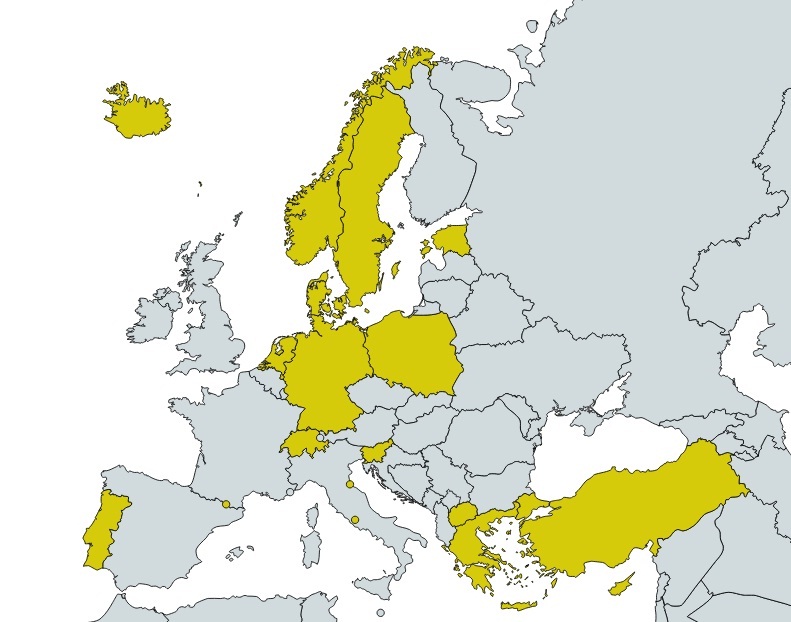

The study systematically reviewed the existence of various types of criminal defamation and insult laws in the 57 OSCE member states. It found that 18 OSCE states maintain criminal defamation laws protecting foreign heads of states: Andorra, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey and Vatican City. Those states are also illustrated in yellow in the map below (OSCE states not shown on the map, i.e., those in North America and Central Asia, do not maintain such provisions)

In terms of sanctions, 17 states – the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia is the only clear exception – foresee the possibility of imprisonment. The highest sanction in this category is in Iceland, where those convicted of insulting the “supreme official or head of state” of a foreign state risk up to six years in prison for serious offences. To gauge the disproportionate nature of this sentence, consider that the maximum sanction for defaming a private person in Iceland is two years behind bars.

Where possible, the study reviewed evidence of application in practice. In general, it confirmed that many of these provisions are, in fact, dormant. In Denmark, for instance, the most recent prosecution occurred in 1934, when a group of persons were sanctioned for calling for an end to the “Nazi’s bloody horror regime”. Turkey, ironically, despite feverish attempts to compel prosecutions in other countries, saw only a single prosecution for insulting a foreign head of state between 2009 and 20015.

The study continues:

“Still, research shows that these provisions are applied more often than perhaps realised. In 2010, the Swiss government – bizarrely – granted permission for the prosecution of a political activist for offending the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddhafi. The activist had put up posters stating that Gaddhafi wanted to ‘destroy Switzerland’, which in turn was a response to a motion Gaddhafi filed at the UN that indeed proposed the ‘abolition’ of Switzerland. Further back, in 1977, the publisher of a Swiss satirical magazine was convicted of insulting the Shah of Iran and sentenced to pay a fine.”

Standard-setting human rights bodies have on various occasions criticised laws protecting foreign heads of state. Most prominently, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2002:

“[Prosecutions for insult to foreign leaders] confer a special legal status on heads of State, shielding them from criticism solely on account of their function or status, irrespective of whether the criticism is warranted. That, in [this Court’s] view, amounts to conferring on foreign heads of State a special privilege that cannot be reconciled with modern practice and political conceptions. Whatever the obvious interest which every State has in maintaining friendly relations based on trust with the leaders of other States, such a privilege exceeds what is necessary for that objective to be obtained. Accordingly, the offence of insulting a foreign head of State is liable to inhibit freedom of expression without meeting any ‘pressing social need’ capable of justifying such a restriction. It is the special protection afforded foreign heads of State by section 36 that undermines freedom of expression, not their right to use the standard procedure available to everyone to complain if their honour or reputation has been attacked or they are subjected to insulting remarks.”

For its part, last June in the context of the Böhmermann affair the OSCE Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media called insult laws protecting foreign heads of state “a special privilege that cannot be reconciled with democratic practice”.

[separator style_type=”none” top_margin=”15″ bottom_margin=”20″ sep_color=”#eae9e9″ border_size=”” icon=”” icon_circle=”no” icon_circle_color=”#ffffff” width=”” alignment=”center” class=”” id=””]

[content_boxes layout=”clean-horizontal” columns=”1″ icon_align=”left” title_size=”18″ backgroundcolor=”#d5cb0b” icon_circle=”” icon_circle_radius=”” iconcolor=”#d5cb0b” circlecolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”#d5cb0b” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” icon_size=”” link_type=”” link_area=”” animation_delay=”” animation_offset=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ margin_top=”0″ margin_bottom=”0″ class=”” id=””]

[content_box title=”Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region” icon=”” backgroundcolor=”#d5cb0b” iconcolor=”#000000″ circlecolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolor=”” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” iconrotate=”” iconspin=”no” image=”” image_width=”35″ image_height=”35″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

This post is part of a series of articles analysing the findings from an in-depth report authored by IPI researchers and published by the OSCE Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media in March 2016. Read the full report here.

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]