New digital and local media are turning to a journalism of solutions across Latin America, filling the void left by the weakness in the public realm, write Andres Schafer and Nathalie Alvaray in this second part of their deep dive into how journalists and media builders are breaking the mold.

Across Latin America new digital media are innovating the long tradition of local media and radio stations operating as a service to the community. They’re filling the void created by weaknesses in the public realm and the state: from literacy campaigns in the countryside to the proverbial urgent search for blood donors for an operation.

And they’re doing so by turning to a solutions-focused journalism to replace the too-easy reporting on an unplaced sewer grate or hole in the street that feeds a malaise of overall collapse. Taken raw, without solutions, there comes a time when this type of reporting ceases to be conducive and instead becomes paralyzing.

It’s a void being filled by new and transitioning digital media, often aimed against the tactics and practices of governments and political actors that expect to benefit from fostering conflict and social polarization because these help to demobilize and coopt people.

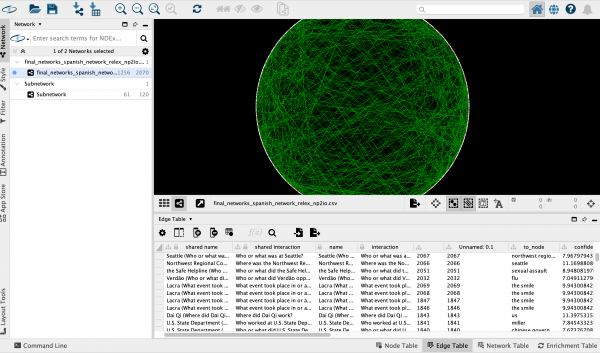

Data as narrative: when facts get meaning

In Peru, an investigative journalism alliance in 2015 with Swiss Leaks and the ICIJ International Consortium of Investigative Journalists was the platform for the Convoca.pe site to launch a data journalism operation that did not exist at the time in other Peruvian newspapers. For Milagros Salazar, one of the founders of Convoca, data journalism allows us to see beyond the raw facts; it is the way to move from a journalism that simply reacts to the agenda of political and social actors to a more proactive one, in which “working with databases allows you to enter in an issue and see it from different angles, approaches, in a much more systematic, systemic and integral way”, she says.

What could have been a mere report on an oil spill thus becomes a more comprehensive overview and an analysis of a whole phenomenon with a method behind it: the impact of extractive industries in the Peruvian Amazon. It is also possible to learn more about the issue through a newsgame: “Clean up a spill“, something similar to what Argentina’s RedAcción does with the phenomenon of disinformation. As part of these efforts, Convoca launched Games for News, a platform to create video games for storytelling without having to write code.

“We went from being a generator of high-quality content to an organization that generates innovative solutions for others”, Salazar says.

With Convoca Deep Data they offer a “freemium” service that allows access to their data tool but that charges a symbolic yearly fee for more advanced features and cross-referencing with other databases. ConvocaEscuela trains journalists in digital storytelling and data processing and ConvocaLab has created narratives with digital comics, 360º videos, podcasts, and other resources.

Screenshot deepdata.convoca.pe

Convoca’s initial audience was a professional middle class with a critical view of reality. Its impact is fundamentally “on the great power”. Milagros Salazar explains: “What do I mean by that? The majority of Convoca’s research… makes the justice system, the prosecutors, the police, the president, the ministers…it makes them move. From the beginning Convoca had the objective of generating changes in public policies.”

However, as the organization has grown, the audience has expanded. The work of ConvocaEscuela attracted a younger audience. In addition, Convoca has made alliances with media outlets with greater penetration in remote areas and with local radio stations. During the COVID-19 pandemic they launched a fact-checking operation through podcasts in indigenous languages, in collaboration with colleagues from Ecuador, Bolivia, and Mexico and the LatAm Chequea network, and also created a service section, Convoca a tu Servicio, that has endured to cover other areas as well. The new readers that come with these programs, Salazar says, “are different, they have a need and come looking for solutions, but by doing so, they discover the research we do”.

And if with its newsgames tool the site is reminiscent of the work of RedAcción and El Surti, with its investigations on corruption (Panama Papers, Lava Jato, among many others), the data tool and the goal of speaking truth to power and influencing public policy finds another equivalent, this time in Guatemala.

Auditing from a journalistic standpoint

The most focused and specific site in this review turned out to be the Guatemalan site Ojoconmipisto, or “Watch out with my money.” Created as part of Laboratorio de Medios, a company run by journalists that offers training and consulting services, its intention is to “oversee (Guatemala’s) municipalities through journalism”. For Ana Carolina Alpírez, founder and director of the site, although the attention of traditional media is usually focused on the main power centres, “corruption does not only happen in the central institutions, it begins at the local level”.

Ojoconmipisto uses data from the official procurement portal Guatecompras.gt, among others, and the Law of Access to Public Information to uncover irregularities in municipal administrations. It has created several databases that can be consulted by its readers, and it teaches citizens how to use the official portal and, with interactive tools, how to audit a municipality. Its YouTube channel contains a collection of informative videos to empower citizens in this regard.

“We have three principles”, Alpírez explains. “Municipal oversight, training, and citizen participation. We are very interested in this part of citizen training. Why? Because citizens are our first source of information, they are the ones on the ground.”

Ojoconmipisto was born out of the need to “tell the stories from the departments”, i.e., the Guatemalan provinces. Previously, when something happened, the established newspapers would send a reporter to the departments because they could not afford to pay correspondents. The result was content that people in the department found flawed and “fell short” because it lacked the local point of view. Ojoconmipisto therefore decided to create a network of freelance correspondents from the departments. But for that it had to train them in data journalism and digital storytelling. By offering diploma courses through the Laboratorio de Medios to these reporters, they were also able, as part of their training, to produce articles that would in turn feed into the website.

“Ojoconmipisto can vouch for every story that is published on the site”, Alpírez says. “We are journalists and we are very clear that credibility is everything. Without credibility, any journalistic project is over.”

She explains that things work somewhat differently in the municipalities: there are media outlets owned by the mayor or a deputy, and it is not uncommon to find journalists who work for an institution and at the same time as reporters. Ojoconmipisto often has to explain to municipalities that there is a Law of Access to Public Information and that the mayor doesn´t have the power or the right to deny any information.

Ojo com mi Pisto’s investigation uncovering two municipal representatives benefitting from public procurement

This digital medium has been creating two audiences. An audience of users and readers in the cities of Guatemala; and also another audience in the local administrations – who know that they are being monitored – and in public institutions such as the Comptroller General’s Office and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which do not have enough personnel and therefore resort to Ojoconmipisto to do their work. The information and databases of the site are also used by other media.

The site’s sources of income are 90 percent from grants and 10 percent from revenues generated by the Media Lab. This forces them to work part-time, and to consider selling advertising. “Journalism is needed”, Alpírez says. “We have to exercise journalism in the country, again and again. What we are doing is important.” She argues that there are two crises in journalism: a crisis of sustainability and a crisis of misinformation. “And in both we have a lot to do.”

Irrigating the information deserts

During 2014 Venezuela witnessed the culmination of a process of “hostile takeover” of almost all media outlets by the government or by front men linked to like-minded businessmen. Many journalists were left on the street, many left the country. Others, after their initial bewilderment, began rebuilding to create a lush ecosystem of alternative and digital media. El Pitazo is one of the first.

Economic problems starting in 2013 and government pressures led to the reduction of operations in many media. Bureaus in the interior of the country were closed. “In some areas of the country, local journalism is practically disappearing” César Bátiz, one of the founders of El Pitazo, says. Like Ojoconmipisto, El Pitazo set out to serve local communities by creating a network of freelance correspondents throughout the country, reaching out to those communities that had been left without information alternatives other than the official ones.

According to Bátiz, many of these correspondents admit that were it not for El Pitazo, they would have joined the Venezuelan diaspora, estimated at 6 million emigrants, or would have dedicated themselves to another activity.

The Venezuelan government is engaged in what could be called an “epistemological war” against part of its population. The struggle is no longer for the supremacy of one narrative but for the establishment of “alternative facts”. The disinformation in this case comes from the government and institutions themselves, with trolls and rumor mills generating opinion matrices on Twitter through a combination of bots and an army of agents organized in military structures and the worst Internet connectivity in Latin America.

In an attempt to fill the “information deserts“, as the Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS) in Caracas called them, media such as El Pitazo took on the task of informing communities.

Starting as a YouTube channel, El Pitazo was forced from the beginning to innovate. With poor Internet connectivity they resorted to SMS and WhatsApp messaging to disseminate news.

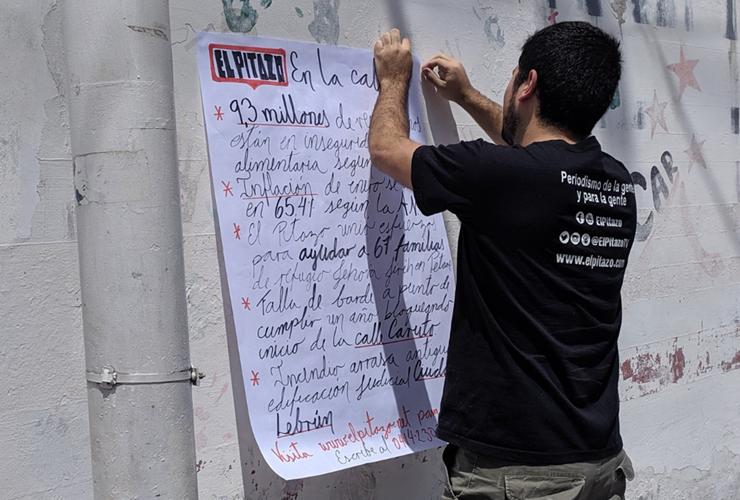

Attacks on its website, which has been repeatedly taken down, led them to street work, what they call “El Pitazo en la Calle”, climbing the hills of the slums in Caracas and other cities to call out the news with a megaphone, and pasting posters with the headlines in schools and community centers.

El Pitazo team glueing posters with handwritten headlines on the walls

They created WhatsApp groups and forums, worked with a network of allied radio stations to disseminate podcasts, and got their journalism out through social networks and through four newsletters, one of which is aimed at Venezuelans in the diaspora. El Pitazo even uses theater to tell the stories of their investigative journalism, turning them into theatre plays, which they call “performance journalism”. They quickly became a generalist journalism content machine with extensive local coverage, resorting to any channel of distribution imaginable.

Like many other journalists in the country, they have been subjected to physical attacks, judicial threats, and harassment, online and in public media.

El Pitazo has found alliances with other alternative media in the country and elsewhere in Latin America, as well as with NGOs, a way to optimize its resources and create synergies, especially in investigative work. These alliances have resulted in works such as Mujeres en la Vitrina, which unveiled a human trafficking network between Argentina, Venezuela, and Mexico; Generación del Hambre, which exposed the situation of child malnutrition in Venezuela; or Covid-19: Negocios bajo Sospecha, produced by the media alliance Vigila la Pandemia, coordinated by Convoca (Peru). El Pitazo also used crowdsourcing together with an alliance of alternative media, electoral observers, and other NGOs, to enable citizen monitoring of elections, an initiative called El Guachimán Electoral, creating a database with irregularities in these processes.

Another way of integrating the audience and enabling participation has been through the training of “community reporters” with the Infociudadanos program and the Un Café con el Pitazo meetings, which are visits to different communities where residents, journalists, and experts come together to discuss certain topics. During the pandemic, the journalist Rena Camacho, in charge of these meetings, decided to create WhatsApp chat forums to continue the activity online. They became an instant success under lockdown conditions and this multiplied the number of participants.

With the communities, doing Un Cafe con El Pitazo which during Covid-19 evolved to the Chat Forums

El Pitazo’s revenue model reflects the uncertain situation of the outlet. Aware of their complete dependence on grants, it became obvious for them that something else had to be done. El Pitazo started to sell paid advertisements together with its allied media, and they also joined forces to fund investigative projects or to pay for cybersecurity. They also ventured into plain programmatic advertising.

After being selected for the Velocidad accelerator, El Pitazo consolidated a dedicated unit for sales and strategy. They began to monetize their YouTube and Facebook channels, and sold ads in their radio news shows. A membership system is in its beginnings, after overcoming a bumpy start with the platform. The WhatsApp chat forums also became a source of revenue from brands and institutions, and they secured sponsors for events.

El Pitazo also launched a satirical “Crisionary” with words and illustrations on the Venezuelan crisis and is about to sell T-Shirts with these motifs. They are considering the use of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) to finance projects.

All in all, El Pitazo realized that more resources and effort had to be put into sales. They introduced a personal approach to their clients, and saw that there is money to be found in Venezuela once you know how to look for it. Still, and even though they are set to almost double their revenue from these sources this year, they continue to rely overwhelmingly on grants and funding. The road to sustainability is uphill. For Bátiz, doing journalism today in Venezuela is like “a marathon that we are running with one leg and with obstacles”.

Offering meaning from isolated facts

Something happens when scattered facts acquire a greater meaning. That’s the challenge taken on by digital native media in Latin America. As El Surti says, it’s the “move from the factual to the phenomenal”, to help the community understand reality and empower them to change things.

These media also understand the double-edged sword the new digital platforms hold: The power to start from scratch with a JPG or a YouTube channel countered with the challenges of news intoxication, rampant disinformation, and the power of what Bátiz calls “the barons of technology”, who “are trying to generate a community of content creators to somehow bypass the media” and make them redundant. They also understand, as El Surti’s Alejando Valdez says, that they have to get out of the “presentism forced by the platforms” and not let “the algorithms become our editors.”

It’s a struggle. It’s a promise. A new generation of entrepreneurial journalists is leading the way with a different self-awareness than their predecessors in legacy media who too often regarded their newspapers or TV stations as a leverage for their own social, political, and economic power. And unlike their platform enablers like Google or Facebook that transform their audiences into products, these digital native newcomers are trying to find new models built on inclusion, empowerment, and participation, upturning with new twists an old tradition of local media as a service. They are the ones now trying truly digital models which may be laying the foundations of journalism in the future.

This story is part of IPI’s Local Journalism Project. IPI’s work mapping, networking and supporting quality innovative media serving local communities is supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation and Craig Newmark Philanthropies.