Imagine a country where the government has abolished the public media licence fee in 2022 and replaced it with a financing based on a percentage of the revenue from value added tax, with no legal guarantees to maintain the funding in the future. The party that won the most votes in the last elections wants to privatize the public media altogether, even if it means selling to foreign companies. In this country, a billionaire who welcomed a former President of the Republic on his yacht the day after his election, owns the country’s largest media conglomerate spanning broadcast and print. In the meantime, this same billionaire has imposed ultra-conservative ideas on his press titles, and two television channels leading to the recent removal of one of their digital frequencies for promoting “a specific opinion”, for their “partisan treatment of election news” and for their failure to respect media pluralism, honesty and independence of information. One of the main national daily newspapers is owned by another billionaire whose main business is the manufacture of military arms and aircraft, with the Ministry of Defence as its main client. During the last elections, the journalists’ unions and editorial teams of many media, both public and private, protested against the “trivialisation of the far right and the demonisation of the left” by some of the media.

That country is France.

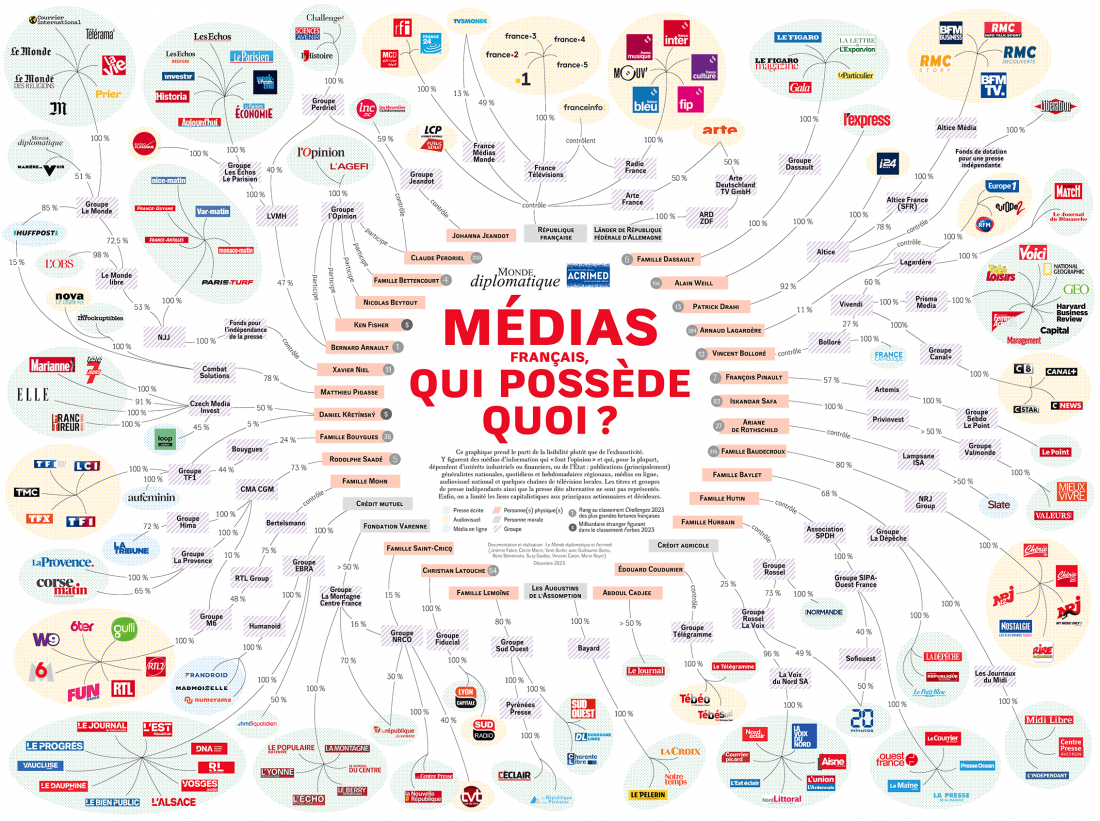

Of course, the general situation of the French media is complex and more nuanced, as shown in the visualization below, produced by the media watchdog Action-Critique-Médias (Acrimed). But this lavish illustration hides a more prosaic reality: in terms of circulation and audience figures, the French media are mostly owned by a handful of billionaires that include the Bouygues family, Patrick Drahi, Xavier Niel and Bernard Arnault (see table at the end of the article). The situation of media concentration in France is all the more remarkable given that the country lacks an efficient framework for complete and real-time transparency of media ownership, despite recurring political promises made during the “Etats généraux de l’information” in 2023.[1]

‘French media: who owns what?’, Jérémie Fabre, Marie Beyer (Acrimed), 11 December 2023

These billionaires and the companies they control draw their power from areas of strategic importance to the national economy, such as telecoms, defence and public works creating inevitable conflicts of interest for their newsrooms. How can a journalist investigate public contracts when they work for a company that benefits from them? How can you analyze financial information if your newspaper belongs to a luxury multinational company whose owner, Bernard Arnault, is one of the richest men in the world?

The French media landscape is also accustomed to certain connivances between a media outlet and a political movement, sometimes openly, sometimes more insidiously, as revealed by the exchanges of text messages between Nicolas Sarkozy and managers of the BFMTV news channel in support of the former president in one of his many legal setbacks in 2024.

But what is new in recent years is that we are witnessing a shift from news media serving the public, to opinion-forming tools at the service of their sole owners interests, or to be more precise, their owners’ ‘values’. While France has not reached

the stage of ‘media capture’ thanks to regulatory safeguards, starting with the Autorité de Régulation de la Communication Audiovisuelle et Numérique (ARCOM), the instrumentalisation of the media for ideological and political ends is reaching critical levels.

From media concentration to “bollorisation of the media”

The case of billionaire Vincent Bolloré is the most telling. Bolloré heads an industrial empire in the transport, media and advertising sectors, across Europe and reaching through Africa. He owns television channels (C8, Cnews, Canal+), radio station(s) (Europe 1), numerous magazines and newspapers, the country’s leading publisher (Hachette) and the ‘Relay’ newspapers sellers chain. 2,359 million people listen every day to Europe 1, and for the first time, CNews became the leading non-stop news channel in France in June 2024, with a general audience rate of 2,8%.

Bolloré is a devout Catholic, who has put his media at the service of his ultra-conservative convictions. He recently acquired the Journal du Dimanche (JDD) before imposing a new editor-in-chief who publicly supports the far-right politician Éric Zemmour. This nomination lead to a forty-day strike in July 2023 followed by the departure of around 60 journalists. But in the absence of formal procedures giving journalists a say over changes of editorial policies, Bolloré “won” the battle to impose his new editor-in-chief. The fact that there are ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’ media is nothing new in France. French “internal pluralism” in broadcasting media does not prohibit the expression of a political editorial line, but it does prohibit the “monochrome” display of a single current of thought.[2]

What is new is the level of cross-concentration of publishing with other media platforms, some of which are accused of being used as tools of ideological propaganda, regularly breaching journalistic ethics. Bolloré is considered a “super influencer”: the “Journal du Dimanche and Paris Match have no economic interest for Vincent Bolloré. They are influential titles”, according to journalist Isabelle Roberts, who is also the co-author of a book about Bolloré. Since 2021, journalists and academics even talk about the “bollorisation of French media”, that sets out to “promote in the public space a model that is both very liberal [economically] and very conservative, and to operate a sort of great media replacement by bringing down the public media”, which goes hand in hand with a “civilisational fight”.

Bolloré also controls the publishing house “Hachette”, where the new management is accused of being politically-motivated, raising the underlying question: which author or publishing part of the conglomerate will dare to publish a book that might displease this powerful shareholder?

The media owned by Bolloré regularly stand out for their political insults and blatant use of disinformation and propaganda – for example in 2022 CNews was accused of deliberately broadcasting erroneous visualizations of polls ahead of the presidential election, and presenting fake police officers on air. The channels Cnews and C8 (which broadcasts the talk shows of controversial moderator Cyril Hanouna) received 47 warnings, formal notices and fines from ARCOM between 2012 and 2024, before C8 finally saw its digital terrestrial television frequency withdrawn in July 2024. These sanctions mainly concern “incitement to hatred and discriminatory behaviour”, and “lack of honesty and rigour in the presentation and processing of information”. To date, Bolloré’s channels are the only ones to have been issued fines (€7.6 million in eight years).

Bolloré’s strategy is dangerous, not least when it inspires other billionaires. The latest example is Pierre-Édouard Stérin, a French billionaire resident in Belgium. The founder of the online gifts company “Smartbox” is an ultra-conservative catholic, supporter of the “French identity” and “christian anthropology”, and opposed to abortion rights. Moreover, media reports reveal his close ties with far-right politicians such as the Le Pen family, and his plans to invest 150 million euros over ten years, to “enable the ideological, electoral and political victory” of the right and the extreme right. He called his plan “Pericles”, which stands for “Patriotes, Enracinés, Résistants, Identitaires, Chrétiens, Libéraux, Européens, Souverainistes”. When he announced his intention to acquire the weekly Marianne in June 2024, journalists went on strike and asked the current owner, Czech businessman Daniel Kretinsky’s company CMI, to look for “new buyers capable of ensuring the editorial independence” and the “economic sustainability” of the magazine. The negotiations were finally dropped in July 2024.

Regulatory intervention

The behaviour of Bolloré’s TV channels led to two interesting developments by the ARCOM.

Firstly, the regulator suspended the broadcasting license of C8. During a 15 July hearing, representatives of the channel presented their “project” for the renewal of the broadcast license. The process was part of a call for tender featuring 24 applicants for 15 licenses. One key criteria was “the imperative priority of pluralism of socio-cultural currents of expression”. At the end of the process, ARCOM decided not to renew C8’ license after February 2025.

Secondly, the regulator adopted a new rule (“déliberation”) on 18 July 2024 concerning respect for the principle of pluralism of thought and opinion. This new rule follows an appeal lodged with the Conseil d’Etat by Reporters sans Frontières (RSF) on 13 April 2022, specifically to challenge ARCOM’s weakness in the face of C8 and CNews’ failure to meet their obligations. Under this new rule, the broadcast media must now “take account of the diversity of currents of thought and opinion represented by all participants in the programmes broadcast“, thus clarifying the distinction between news media and propaganda tools. RSF has since been the target of a disinformation campaign orchestrated by a ‘communications’ agency belonging to Bolloré’s family.

Conclusions: more pluralism and better media governance

So, what can be done about it?

First of all, it is salutary that ARCOM, long considered a “sleeping beauty”, has finally assumed its responsibilities, and its role could be strengthened in the future, provided the political independence of its members is guaranteed. This goes hand in hand with the work of an independent self-regulatory body, and it is desirable that all the media, including the audiovisual media, join the Council for Journalistic Ethics and Mediation (CDJM).

Secondly, France urgently needs to adopt binding measures on full transparency of media ownership, accessible to all, as set out also in the European Union’s Media Freedom Act. At the same time, France should review its law in media concentration, currently dated back to 1986, to take into account new developments such as technology, digitalisation, local news and cross-media ownership..

Finally, France should lay the foundations for democratic governance of the media, based on a number of proposals and criteria put forward by a coalition of over 100 media and organizations during the “Etats généraux de presse indépendante” in November 2023: validating the choice of editorial director by a majority of journalists (“droit d’agrément”), representing employees on the board of directors or supervisory board, giving employees the right to vote on the new shareholder in the event of a change of majority shareholder. This would mean, for example, creating a “legal status for editorial staff”, that would give them some rights over the editorial line. Many French media (including those owned by billionaires) benefit from state aid and requiring media to guarantee minimum journalistic standards as a condition for public money does not seem unreasonable.

The French media landscape needs to react quickly if it is to live up to the standards of a democracy that is at the mercy of a swing towards illiberalism and authoritarianism at every election.

Which billionaire owns what: a short overview

| Name, rank in French fortunes, estimation in EUR, main business | Media operations |

| Bernard Arnault (1) 190 billion LVMH. Luxury |

Groupe Les Échos-Le Parisien

Le Parisien, daily circulation 188,000 (3rd regional news nationwide)

|

| Dassault Family (5) 28 billion Dassault Group Aerospace, defence, electronics, real estate |

Groupe Figaro

Le Figaro, daily circulation 355,000 (2nd national) Also Madame Figaro, weekly circulation 387,000 (1st “feminine magazine”).

|

| Vincent Bolloré (11) 11 billion Bolloré Goup Transport, logistics, energy distribution, plastic films, batteries and electric vehicles, investments in agricultural assets (plantations). |

Vivendi (Groupe Canal, Prisma Média)

Television and radio: Newspaper and magazines: Télé Loisir, weekly circulation 467,000 (3rd news application on mobile phones in France with 521 millions visits in 2023) GEO, weekly circulation 101,000 (1st “travel and tourism media” in France) Capital, monthly circulation 89,000 (1st “Business and finance” magazine, also 2nd business website with over 263 millions visits in 2023) Femme Actuelle, weekly circulation 360,000 (2nd “feminine magazine”) Le Journal du Dimanche, declining circulation, especially since the takeover by Mr. Bolloré (from over 200,000 weekly copies in 2024 to less than 100,000 currently). Gala and Voici, both are in the top five tabloid magazines (“presse people”) Paris-Match, the iconic weekly magazine, is the 3rd general news weekly magazine in terms of circulation with around 540,000 copies. It is currently being sold to Mr. Arnault’s LVMH company; the deal was approved by the competition authority on 6 August 2024. |

| Patrick Drahi (14) 8,6 billions Altice Telecom and media |

Altice (Altice France, Altice Média)

Television and radio:

|

| Bouygues family (21) 4,3 billions Bouygues Group Construction, real estate, energy and telecom |

Bouygues (Groupe TF1)

The TF1 group owns general and thematic television channels, free and paid. It results from the privatization of the 1st public TV channel in 1987. In 2023, the various free channels of the TF1 Group gathered around 27% of the total national audience share, with 19% for TF1 alone, by far the leading private channel in France. |

Source for wealth: Les 500 plus grandes fortunes de France

Source for circulation and audiences: Alliance pour les chiffres de la presse et des médias and The Media Leader

Footnotes

- The law of 4 November 2016 on “Strengthening the freedom, independence and pluralism of the media” stipulates that “each year, the publishing company must bring to the attention of readers or Internet users of the publication or online press service all information relating to the composition of its capital, in the event of holding by any natural or legal person of a fraction greater than or equal to 5% of it, and of its management bodies. It mentions the identity and share of shares of each of the shareholders, whether a natural or legal person”. However, this does not take into account the various changes during the year, and it does not foresee any transparency requirement about the activity or economic profile of the shareholders.

- The law of 30 September 1986 on “freedom of communication” imposes on TV channels an “internal pluralism”. This is a notable difference with the written press and web media governed by the principle of “external pluralism”. The profusion of written press titles and websites is supposed to offer the possibility of opinion media, as opposed to the limited number of TV licenses. It is up to the regulator, Arcom, to monitor the compliance with internal pluralism in the audiovisual sector.

This article was produced as part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors, and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. The project is co-funded by the European Commission.