To mark World Press Freedom Day, IPI’s media partners in the South Asia Cross-border journalism project in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Nepal have documented several press freedom violations in their countries. These stories are published in all the five news publications – The Daily Star, The Week, Dawn, Republica and Nagarik.

Filthy curses, and the gleam of a pistol. That is about all the barber says he knows of the attack on Ajay Lalwani as the journalist sat getting a shave from him on the evening of March 17 in Saleh Pat, located in Sukkur district of Sindh province. The street outside was in darkness because of a power cut; a couple of emergency bulbs provided the only light inside. “A voice ordered me to move to the back of my shop,” recalls Khalil Ahmed the barber. Then came the gunshots. Two bullet holes can be seen in the barber’s chair where Ajay sat.

Bleeding profusely, he was rushed to hospital, but died the next day. The 27-year-old’s untimely demise removed from the scene a ‘troublesome’ journalist who raised difficult questions with local authorities.

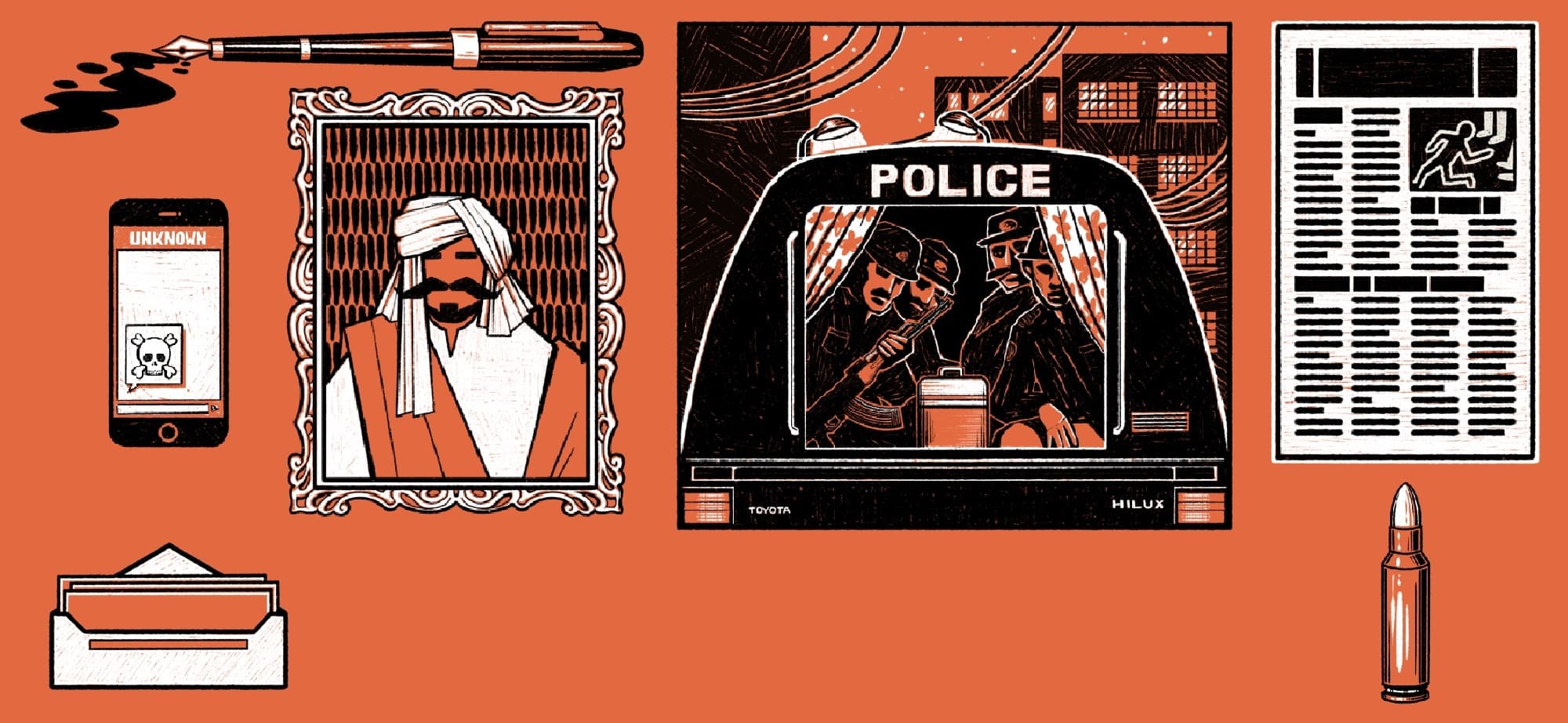

Today is World Press Freedom Day, and the experiences of journalists in upper Sindh alone illustrate the price that media practitioners in Pakistan can expect to pay if they dare speak truth to power. Threats, beatings, trumped up criminal charges, even murder.

The International Federation of Journalists has ranked Pakistan as the fifth most dangerous place for the practice of journalism, with 138 media persons here having lost their lives in the line of duty from 1990 till 2020. Media professionals all across the country are targeted with impunity by militants, criminal elements, government actors, and security agencies.

“Journalism has been taken hostage here,” says Imdad Phulpoto, Sukkur district bureau chief for Abb Takk News. He is among the few journalists willing to be quoted by name for this story. “We leave home not knowing whether we’ll see our families again.”

In this part of Pakistan, known as upper Sindh, an oppressive feudal system brooks no dissent, and the police, far from enforcing the law, act as the waderas personal force. At least 25 FIRs on fake grounds have been filed against various journalists in Sukkur over the past 18 months alone. The charges include serious offences such as waging war against Pakistan, kidnapping for ransom, dacoity, rioting and rape.

Zaib Ali, local bureau chief of Sindh TV at Badah town in Larkana, another district in upper Sindh, reveals that when he reported on the sale of illicit liquor in Badah, his brother was arrested that night for gambling. Ali Raza of Awami Forum newspaper was picked up by police after he reported on forests being cut down, and threatened with being disposed of in a staged encounter.

The PPP’s top bosses are known to have a stake in several TV channels, which adds to the pressure. In September 2019, one such channel ran the video of a young dog bite victim in Shikarpur dying in his mother’s arms for lack of the rabies vaccine. The clip went viral and brought down the wrath of the Sindh government on the reporter. His colleague told Dawn, “The channel was ordered not to run any more reports about dog bite incidents, and they’ve had to comply.”

Unlike other parts of the country where news desks at television channels receive calls from ‘unknown numbers’, intelligence agencies do not often interact with journalists to that extent in upper Sindh. Most media persons anyway desist from reporting ‘sensitive’ news. “There is an ongoing protest for missing persons outside the Larkana press club,” says a reporter. “It never finds a mention anywhere.”

There is another relevant issue here — the rot within the media landscape itself. It is well known that the press in Pakistan is going through a financial crisis. Massive retrenchments have taken place and salaries slashed. That said, most district correspondents have never been paid a salary, especially in Sindhi media. Such a system cannot but encourage corruption in the form of news coverage for sale, or the lack of coverage, as the case may be.

Certainly, journalistic integrity can still be found, but it is a luxury that only salaried correspondents, those with family wherewithal or a second job which brings in an income, can afford.

It was not always this way. Sindhi media was in fact well known for its progressive leanings. “After the Soviet Union’s breakup in the late ‘80s, all the leftists in the province went into journalism,” says Mashooq Odhano, KTN bureau chief in Larkana. It was the mushrooming of electronic media, believes the seasoned journalist, that sparked a decline, with vacancies far outstripping the supply of competent individuals. “There used to be a romance about journalism. That is now gone.”

Nevertheless, the first step towards improving the media environment is to provide a secure environment for journalists. It has been some time that the human rights ministry drafted the Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Bill. Given the dire circumstances in which the media works, such legislation is urgently needed.