Kashmir: Unabated attacks against journalists exacerbate media repression

By IPI Contributor Salomé Cloteaux

July 14, 2022.

From arbitrary arrests and detentions to communications blackouts, journalists in Indian-administered Kashmir operate in one of the world’s most difficult and restrictive environments. IPI continues to monitor and document the alarming deterioration of press freedom in the region, which has significantly worsened since the Indian government revoked the state’s special status three years ago.

This decline has occurred amid broader attacks on press freedom in India under the government of conservative nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose Bharatiya Janata party has fueled anti-Muslim sentiment.

While the Indian government has always sought to tightly control the media in Kashmir, the situation for independent journalists in the predominantly Muslim region has sharply declined since the government in August 2019 repealed Article 370 and 35a of the Indian Constitution, which gave Jammu and Kashmir significant autonomy. Since then, the region’s independent journalists and media outlets have come under intense pressure, facing arbitrary detention and arrest as well as internet shutdowns, which have prevented them from communicating and publishing their work.

A consistent target of government harassment has been the independent weekly The Kashmir Walla. The outlet’s editor, Fahad Shah, has been arrested multiple times this year. He was first arrested on February 4 under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) for uploading “anti-national content”. He was arrested two more times before being jailed under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA) in March while he was still in police custody. On May 20, he was arrested for a fifth time, according to The Indian Express.

Fahad Shah. Photo courtesy The Kashmir Walla.

Another journalist at The Kashmir Walla, Sajad Gul, was arrested in January 2022 under the PSA for sharing “disinformation” on social media after he posted a video of a protest. He had been booked the previous year for reporting on a demolition drive. Fazil, Shah and Gul are still in jail today.

On June 2, authorities questioned Yashraj Sharma, the interim editor of The Kashmir Walla, as part of an investigation about an article, ‘The Shackles of Slavery Will Break”, published by the magazine in 2011, according to reports. In January 2021, Sharma had been charged alongside The Kashmiriyat reporter Mir Junaid with intent to cause riot and public mischief.

Sharma joined The Kashmir Walla in 2018 and was only 12 years old when that article was published. The States Investigation Agency (SIA), a newly set up specialized body investigating terrorism cases, said the article was “highly provocative, seditious and intended to create unrest in Jammu and Kashmir”, according to The Wire.

The author of the article, Abdul Aala Fazili, who is a PhD student at the University of Kashmir, was arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) on April 17. The SIA also raided his residence, The Kashmir Walla office and the home of Fahad Shah.

Draconian laws used to harass independent journalists in Kashmir

The spate of detentions and arrests of journalists at The Kashmir Walla exposes the troubling pattern of the use of laws—including anti-terrorism and preventative detention laws—to target Kashmiri journalists.

These recent incidents also come as part of an escalating pattern of press freedom violations in Modi’s India. The government has passed numerous laws and policies that civil society and journalists say are having the effect of criminalizing journalism.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) criminalizes any activity intended to “cause disaffection against India”, “disrupt the sovereignty and territorial integrity of India” or incite individuals to bring about the cession or session of part of the territory of India.

The law has often been used to silence critical journalists. An amendment to the law introduced in 2019 empowers the government to designate individuals and organizations as terrorists—and puts the burden of proof on the accused to show they are not terrorists. Rights groups have criticized the UAPA over arbitrary provisions that have been widely used by the government as a tool to criminalize and stifle dissent. Under this law, authorities can arrest and conduct a search-and-seizure operation without a warrant if they suspect a person is associated with an unlawful group.

The Public Safety Act (PSA) is another tool used by authorities to crack down on independent journalists. The PSA is an administrative detention law that allows for the preventative detention of any individual for up to two years without a warrant, trial or specific charges. A person is taken into custody under this law to prevent them from acting against “the security of the state or the maintenance of the public order”.

The detaining authority does not need to inform persons charged under the PSA of the reason for the arrest, and the detained person does not have the right to challenge the arrest or engage a lawyer to represent them. The PSA can be slapped on people who are already in police custody or who were just granted bail by a court. In 2018, the law was amended to allow detainees charged under the PSA to be transferred to jails outside the state and away from their families.

Detainments under the PSA have spiked since August 2019, when Kashmir’s special status was revoked. More than 5,000 “preventative arrests”—which are arrests of individuals who authorities suspect will commit a wrongful act in the future—were made between August and December 2019 in Jammu and Kashmir alone.

Journalists protest in Kashmir financial pressure from government is a deliberate attempt to stifle independent. Source: Gowhar Geelani.

Almost a year after the revocation of the region’s semi-autonomy, in May 2020, the Jammu and Kashmir Department of Information and Public Relations announced a new media policy that authorizes government officers to “examine the content of the print, electronic and other forms of media for fake news, plagiarism and unethical or anti-national activities” and mandates background checks for journalists.

Local journalists protested the policy, worrying it will make it easier for the government to go after reporters and publications, according to The Wire. Critics have said the policy—which was released in June 2020—is inconsistent with India’s constitution, and its undefined checks on fake news are intended to justify the crackdown on journalists.

In another effort to censor independent media, authorities have placed travel restrictions on more than 40 people, including 22 journalists, barring them from traveling outside of India. The restrictions, known as “look out notices”, are not made public—those on the list remain unaware until they seek to travel abroad and are stopped at the airport. Analysis suggests that the government does not want journalists working for international organizations to share with the rest of the world what is happening in Kashmir.

The Jammu and Kashmir administration has also increased state surveillance and control of the media by issuing an order in August 2021 forcing “unauthorised/unregistered” journalists to “complete their registration or obtain approval” before they perform their jobs, and authorities can stop journalists who threaten public tranquility or peace.

Communications blackouts: shutting off the internet in Kashmir

Kashmir is the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan, both of which control parts of the contested region. In Indian-administered Kashmir, India has deployed troops since the late 1980s to suppress an armed insurgency along with movements for independence or union with Pakistan. Tensions and rebellions continue to erupt periodically, making the Kashmir Valley one of the most heavily militarized zones in the world today.

On August 4, 2019, the government suspended landline, mobile and internet services in Kashmir. The internet shutdown lasted 552 days, until February 6, 2021, making it among the longest communications blackouts ever imposed in a democracy.

During most of the shutdown, the internet could only be used in a government-run centre, and internet access was only permitted for some government-approved websites, excluding many social media sites. Access to 4G was only restored after 552 days of partial or no internet access, greatly hindering journalists’ ability to access and share information for months.

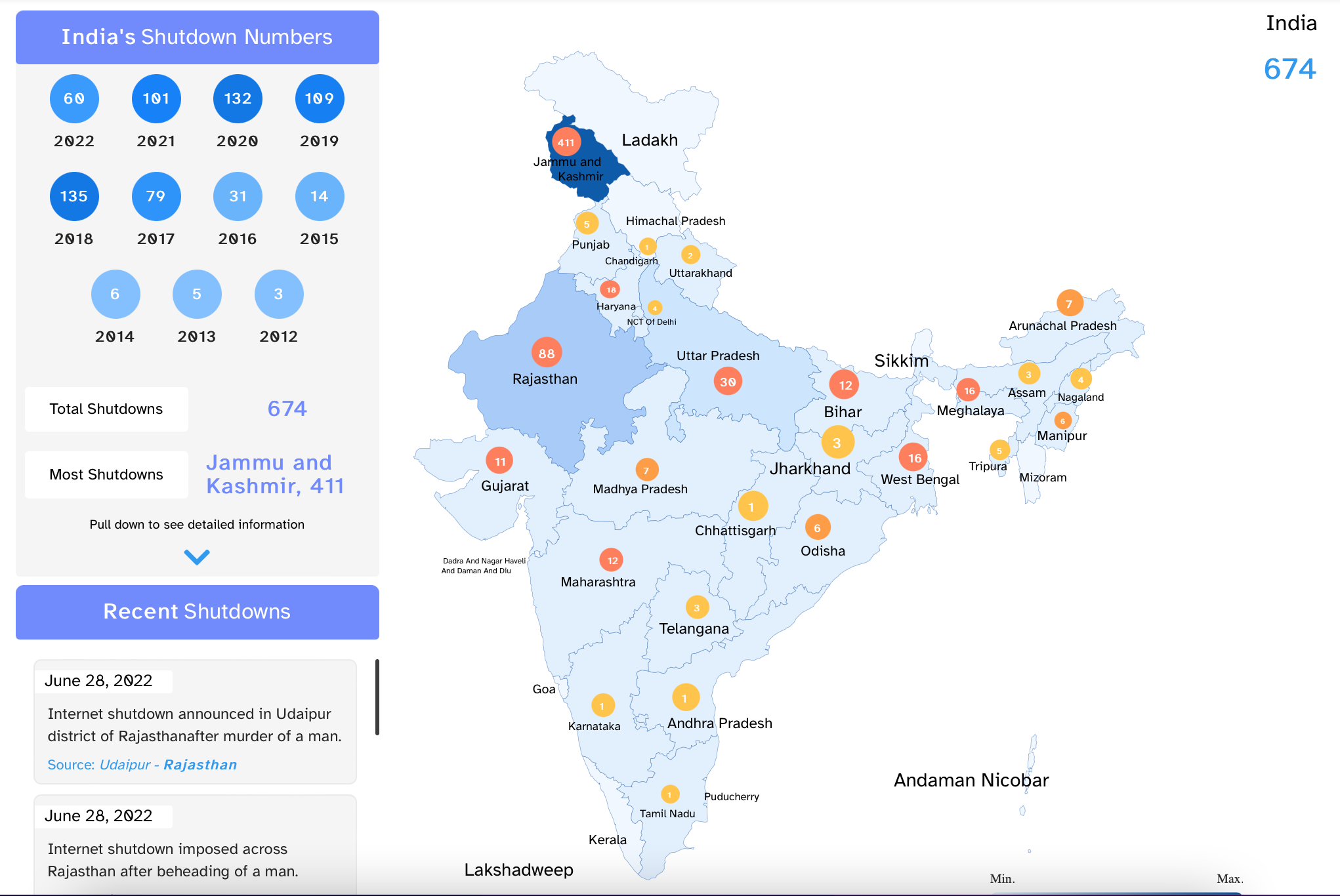

The communication shutdown resulted in severe restrictions on press freedom, including the surveillance and harassment of journalists, according to a report by the FreeSpeechCollective, an organization that aims to protect the right to freedom of expression, in September 2019. In 2021, Jammu and Kashmir experienced at least 85 internet shutdowns, more than any other place in the world, under the guise of “counterterrorism” measures by the government, according to digital rights advocacy group, Access Now.

“Internet Shutdowns” track incidents of Internet shutdowns across India in an attempt to draw attention to the troubling trend of disconnecting access to Internet services, for reasons ranging from curbing unrest to preventing cheating in an examination. This graphic is presented with permission from the Software Freedom Law Center of India (https://internetshutdowns.in/).

Rising number of journalist detentions

The Kashmir Walla journalists are just a few of the many reporters targeted amid a crackdown on the independent journalists in Kashmir. According to The Kashmiriyat, as many as 49 Kashmiri journalists experienced incidents of harassment, arrests, or intimidation in 2021.

Meanwhile, Kashmir is inaccessible to foreign correspondents, unless they have been granted rare official approval, so most of the reporting in the region comes from local journalists facing raids, threats, interrogations, arbitrary arrests and harassment.

Kashmiri journalists hold placards during a protest against the communication blackout at Press Club Kashmir in Srinagar, The summer capital of Indian Kashmir, Oct. 3, 2019. EPA-EFE/STRINGER.

For example, in September 2017, photojournalist Kamran Yousuf was the first Kashmiri journalist charged under the UAPA. According to reports, he was framed by the National Investigation Agency, the primary counter-terrorist task force of India, and he was released on bail six months later. The case against him was dropped in March 2022 due to lack of evidence. In September 2020, he was assaulted by police when he was covering a gunfight.

Aasif Sultan, a journalist with the independent monthly magazine Kashmir Narrator, was also arrested under the UAPA for “harboring known militants” in August 2018 according to reports. He was granted bail in April 2022 but was rearrested a few days later under the PSA after already spending almost four years in jail.

Kashmiri journalist Qazi Shibli was detained and charged under the PSA in July 2019 for reporting on the deployment of troops before the Indian government took control of Jammu and Kashmir. He spent nine months in jail without trial.

On April 19, 2020, the cyber police in Srinagar called in Peerzada Ashiq, senior journalist of The Hindu, for questioning about a report described as “fake news.” In the two days that followed, J&K police booked Kashmiri photojournalist Masrat Zahra and independent journalist and author Gowhar Geelani under the UAPA for their social media posts, according to reports. Under the UAPA, Zahra and Geelani could face up to seven years of imprisonment.

Journalist Auqib Javeed was summoned to the Cyber Police Station where he was questioned and slapped for writing a “misleading and factually incorrect” story in September 2020, according to reports.

A year later, in September 2021 Jammu and Kashmir police simultaneously raided the residences of four Kashmiri journalists — Showkat Motta, Azhar Qadri, Abbas Shah and Hilal Mir — seizing documents and electronic devices. The journalists were questioned and detained for a day at a local police station, according to reports.

In October 2021 the NIA raided photojournalist Manan Gulzar Dar’s residence and arrested him for allegedly working with terrorist organizations under the UAPA. This was part of a series of about 130 raids conducted by the NIA in Jammu and Kashmir during four months in 2021.

That same month, in the span of one week, five journalists were summoned and detained by the police and investigative agencies, including Salman Shah, editor of the Kashmir First; Sajad Gul, a freelance journalist; Suhail Dar, a freelance journalist who had previously detained under the UAPA in 2020; Mukhtar Zahoor, a stringer with the BBC; and Majid Hyderi, a freelance journalist.

Indian police and paramilitary men patrol at the site of gunfight on the outskirts of Srinagar, the summer capital of Indian Kashmir, 03 January 2022. EPA-EFE/FAROOQ KHAN

The summoning and interrogations of journalists have created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty. Journalists who are summoned and questioned for their reports or their social media posts are told that they are “under watch”. Over the last year, even the families of journalists have been summoned and questioned.

In July 2021, Zahra’s parents were accosted and stalked by police in the city of Srinagar. Journalist Shahid Tantray, from The Caravan magazine, also said police harassed and questioned him and his family about his reports on Kashmir this year. Tantray was summoned by J&K police in June 2022 over a “mischievous” article he published in the magazine.

“The continued intimidation and harassment of journalists in Kashmir has had a chilling effect on their work for some years now”, Geeta Seshu, co-founder of the FreeSpeechCollective, told IPI. “However, the latest pattern of issuing summons and interrogating not just the journalists, but also members of their families, conducting raids on their residential premises or the work-places of family members, is an attempt to intimidate their near and dear ones and rob the journalists of their emotional and social support.”

Censorship of independent media

In addition to attacking and threatening individual journalists, the state targets independent news outlets and organizations in Kashmir that continue to report factual stories despite the crackdown on the press.

Recently, several journalists in Kashmir have said their work, especially stories critical of the government, has disappeared from the digital archives of local newspapers. They say it is a deliberate attempt to twist history, according to reports.

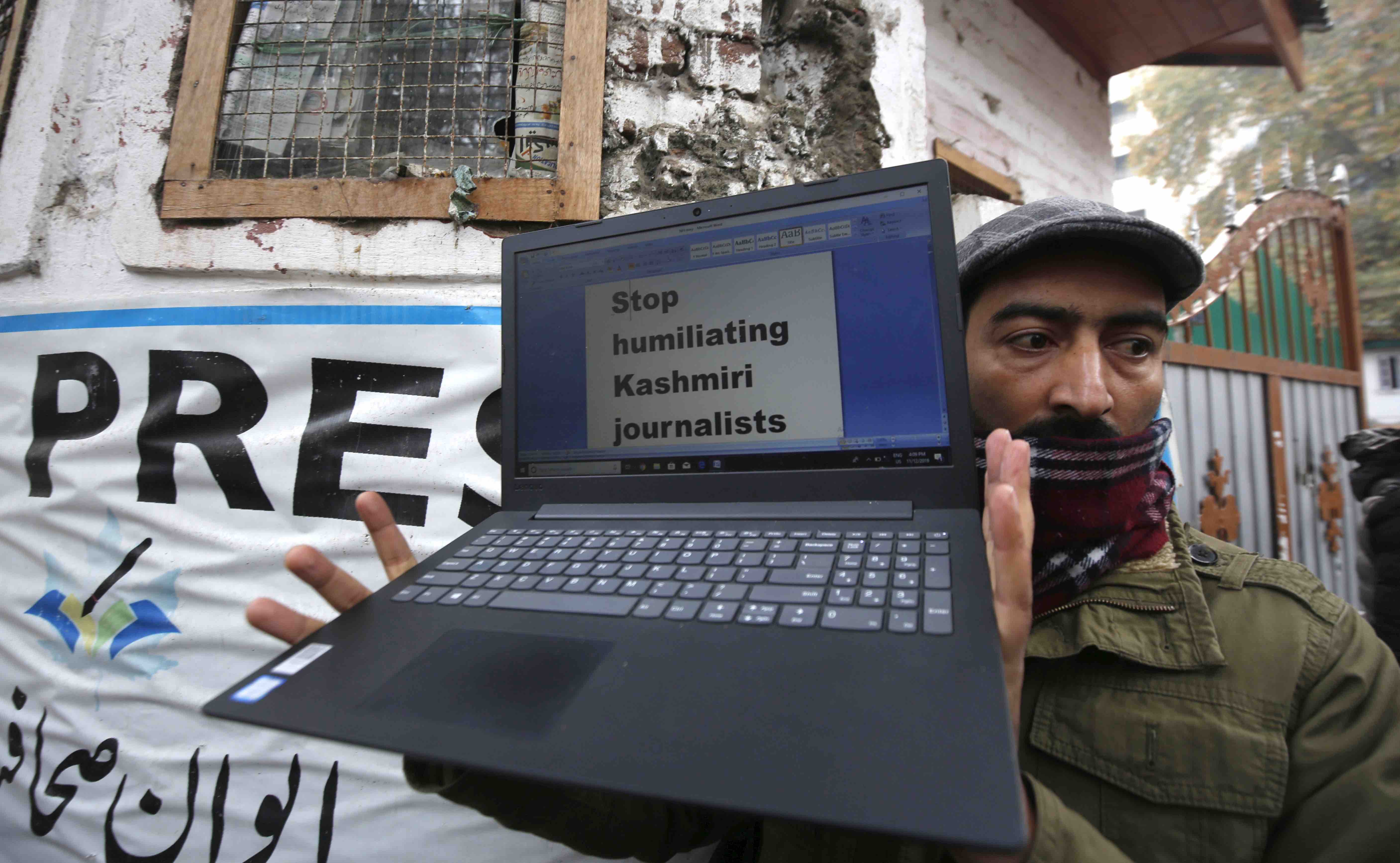

A Kashmiri journalist holds laptop during a protest against the ongoing internet blockade that completes 100 days in Srinagar, Indian Kashmir, 12 November 2019. EPA-EFE/FAROOQ KHAN

In January 2022, a group of pro-government journalists took over the Kashmir Press Club, and it was subsequently shut down by authorities. The surprising overthrow of the KPC, the largest body of independent reporters in the region known for its critical reporting and for defending press freedom, highlights the rapid erosion of press freedom in Kashmir.

In October 2020, Indian officials sealed the office of the Kashmir Times, a leading English daily and one of the oldest newspapers in the region, without any due process or notice. Local journalists condemned the action, calling it “government-sponsored intimidation attempts to silence an independent newspaper.”

The state has censored and kept other newspapers in check through government ads, as many news outlets in the region rely on revenue from state advertising. In 2019, the J&K government denied advertisements to two major newspapers, Greater Kashmir and the Kashmir Reader. It removed 30 more newspapers from a list of outlets approved for state ad revenue in 2021 for violating the 2020 media policy. The ban of government advertisements, an important revenue source, is a cost many media outlets can’t afford.

Afraid for their safety and at risk of losing their main source of income, many newspapers and journalists are reportedly turning to self-censorship, staying away from controversial stories and writing anonymously. Financial pressure, surveillance and harassment by authorities have created a chilling effect on press freedom in Kashmir.

The hostile atmosphere in Kashmir has forced local journalists to leave the Valley. Those reporters who stay say they are not able to write stories out of fear of repression and have not been paid for months.

The exodus of journalists and the silencing of critical voices has created a void of reporting in Kashmir. Still, despite the unprecedented levels of violence and harassment against independent media, many journalists remain, trying to tell the stories of Kashmir.