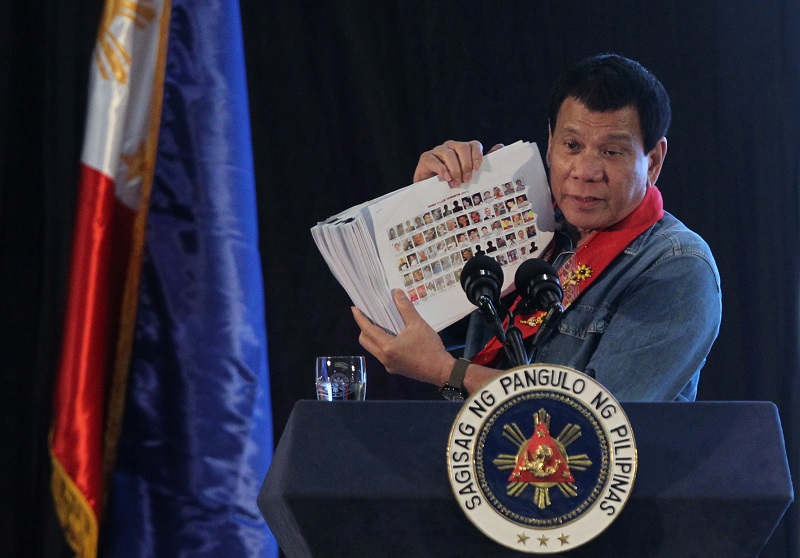

Seven months into the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, press freedom remains under pressure in the Philippines.

The country has been one of the most dangerous for journalists in recent years – the International Press Institute (IPI) has recorded the deaths of 128 journalists in connection with their work since 1997 – and only one week into the year it mourned the first journalist killed in 2017.

On Jan. 6, Mario Contaoi was riding his motorbike home to Magsingal Town on a national highway when unidentified assailants on motorbikes shot him six times. The former university professor, radio announcer and environmental activist succumbed to his injuries in the early hours of Jan. 7.

Just three weeks earlier, Larry Que, a Filipino publisher-columnist, was shot dead after alleging that local officials had ties to the manufacture of illegal drugs.

The circumstances and killers’ motives in both murders remain unclear, highlighting the impunity surrounding journalists’ killings in the country and the lingering threat it poses to their safety.

Since Duterte took office on June 30, he has gained an international reputation for his controversial statements and extreme positions. The war on crime and drugs launched in July that was a focus of his populist campaign is estimated to have taken 6,000 lives, many in summary and extrajudicial killings.

Seven months into Duterte’s term, IPI spoke with journalists and civil society representatives in the Philippines to take a closer look at press freedom and journalists’ safety.

Touchy Relationship

The president has had a touchy relationship with the media. Just weeks before his inauguration, Duterte said in a May 31 press conference that journalists who were killed were responsible for their own fate “because they extorted, accepted bribes, took sides or attacked their victims needlessly”.

The statement drew vociferous objections from both media and civil society groups. They argued that Duterte’s comments not only reinforced the misconception of journalists as corrupt, but also created a fiction that only corrupt journalists had been killed, justifying their murder.

In an interview with IPI, Kathryn Roja Raymundo, press freedom alerts and communications officer for the Bangkok-based Southeast Asian Press Association (SEAPA) disputed Duterte’s allegations.

“Based on evidence, journalists and media workers in the Philippines were murdered for doing their work investigating and exposing corruption,” she said. “Killing is killing and should not be justified or condoned, especially by government officials elected to promote and protect the rule of law.”

In fact, according to the Centre for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR), a local NGO based in Makati City, only eight to 10 percent of all journalists killed since 2000 were actually involved in corrupt practices.

Early Missteps

Beyond his pre-inauguration statements, Duterte made other early missteps, including limiting access to information and press conferences, and flip-flopping on statements. Observers argue this contributed to misconceptions and set back efforts to improve media literacy in the Philippines.

“Many Filipinos do not understand how the press works, particularly its adversarial function in a democratic society,” Melanie Pinlac, Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists coordinator for CMFR, commented.

Roja Raymundo said that, in the Philippines, actions that impair press freedom tend to be extra-legal, rather than the result of specific laws or direct government intervention. But Pinlac argued that Duterte’s openly negative attitude towards the press has taken a toll on journalists and other media workers.

“They are more cautious in newsgathering and reporting about the programs of the current government, and vigilant in monitoring the war on drugs,” she said.

Unfortunately, Duterte’s cynicism towards the press appears to be catching on among his supporters. Journalists who criticize the president’s policies or cover sensitive topics like drug trafficking or corruption face defamation suits and an online backlash. Duterte’s supporters attack them outright or report their online accounts to social media platforms, demanding the takedown of “inappropriate content”.

Roby Alampay, editor-in-chief of Filipino BusinessWorld and InterAkyson, criticised the platforms for their reaction.

“When it comes to Facebook in particular, I am less concerned about fake news and gullibility of people, I am less concerned about the algorithms of Facebook, and more concerned about Facebook’s inability to stand up and defend journalists that they have recognised, journalists with certified accounts,” he told IPI.

The dynamics of social media mean that this stifles not only journalists, but society. Alampay said that in the current climate, no public debate or exchange of ideas is encouraged and Duterte supporters are quick to silence any dissenting opinions. Online harassment causes exhaustion and fatigue, if not fear, in society.

“It is like debating with a wall,” he said. “It is like debating with a drunk.”

Reason for Hope?

Nevertheless, some journalists say there is reason for hope. Alampay said he believes that the press in the Philippines is still among the freest of the region and that, despite Duterte’s personal hostile attitude and often bad behaviour, he is still accessible and willing to answer journalists’ questions.

There also have been positive developments. In late July, Duterte issued an executive order promoting access to information. Although the right is guaranteed by the Philippines’ 1987 Constitution, many citizens are not aware of their rights, Pinlac said.

The executive order is a step in the right direction, but observers say that similar legislation applying to all government bodies should be adopted to ensure the public’s access to information.

In October, Duterte also signed an administrative order creating a “Presidential Task Force on the violation of the right to life, liberty and security of members of the media”. The Task Force is intended to provide security to those under threat and to monitor cases of killed journalists to address the prevailing impunity with which those cases have been met.

Roja Raymundo noted that, since 1986, only 17 people have been convicted in the killings of journalists who died in connection with their work.

Both her organisation and the CMFR have made recommendations to the government on improving the press freedom situation; chief among them is the creation of a multi-stakeholder quick response team, including representatives of media and civil society. The groups also suggested reviewing investigation practices and rules of court that are prone to abuse.

Alampay cited a need to change a misconception of journalism in society, commenting that learning about information and media literacy should start “as soon as kids have email and access to social media”.

However, whether Duterte will manage to effectively address these pressing issues remains to be determined. Although orders on access to information and the safety of journalists spark hope, similar efforts by previous administrations were unable to end impunity and offer real safeguards for journalists.