The murder of Ahmed Hussein-Suale, an investigative reporter at Anas Aremeyaw Anas’s organization Tiger Eye PI, is no closer to being solved. After exposing corruption in African football last year, Ahmed was killed in Accra, Ghana, on January 16th by unidentified gunmen on motorbikes while returning home from work. Over two months later, the investigation into Hussein-Suale’s death appears to have stalled at the hands of powerful adversaries, Anas said in a recent interview with the International Press Institute (IPI).

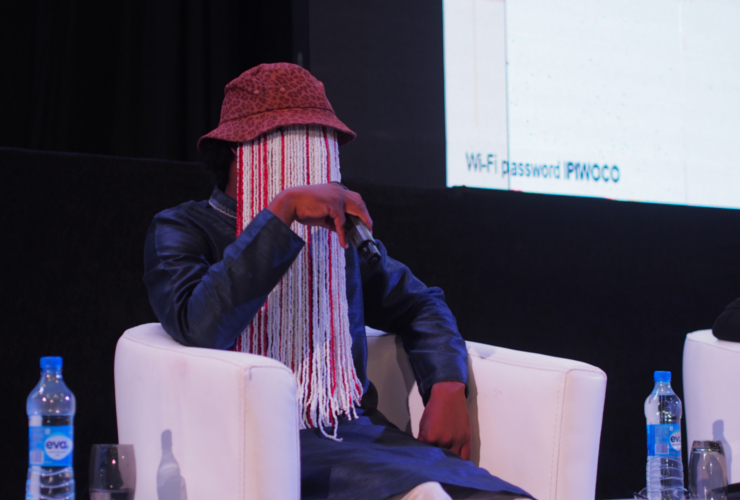

Known for his “name, shame and jail” style of undercover journalism, Anas masks his identity and uses hidden cameras to expose corruption and human rights abuses in Ghana and sub-Saharan Africa. His work has been lauded by Barack Obama and Bill Gates, but has created powerful enemies. In its most notable exposé, Tiger Eye broadcast footage of high-ranking African football officials accepting bribes in a documentary last year called Number 12. In doing so, the journalists “stepped on very powerful toes within the country”, Anas said.

The fallout of the investigation was forceful. FIFA fined the head of Ghana’s football association, Kwesi Nyantakyi, almost $500,000 and banned him for life; Nyantakyi was also accused of requesting $11m to secure government contracts. Lower down the chain, 53 officials were issued 10-year bans and eight referees and assistant referees were banned for life.

As careers were toppled, Tiger Eye journalists became the targets of threats. Ghanaian member of parliament Kennedy Agyapong labelled Anas an “extortionist” and even suggested he should be attacked on the street and hanged.

“We [everyone involved in the investigation] were all targets – and we are still targets”, Anas told IPI. “Ahmed was a target because of the football investigation. I am not surprised, judging by the power of football and the political implications.”

Two months after Hussein-Suale’s murder, Anas says football’s political power may be obscuring justice. While Anas said he was initially optimistic about the police investigation, the police have now developed “cold feet” and achieved minimal progress. Impatient, Anas is conducting his own research into the killing.

“There is some level of apathy within the police service – people are not forceful enough”, Anas commented. “We are not finding a solution to the murder.”

He added: “It is power play. The people in football are very rich people (and) there are some powerful sources making sure that we don’t find the killer.”

For peaceful Ghana, such violence against journalists is rare. However, six journalists were killed elsewhere in Africa last year for reasons connected to their work, according to IPI’s Death Watch. Analysis of Death Watch data highlights that many investigations into targeted journalist murders are slow and fail to bring perpetrators to justice.

In such cases, it is crucial for the international community to apply pressure on governments and law enforcement. However, Anas emphasized that “the real battle must be led and fought by Ghanaians, ourselves. No one else can fight for us.”

Despite what he describes as daily death threats, Anas is continuing Tiger Eye’s investigative work. In February, the team published evidence of corruption within committees established by President Nana Akufo Addo to end illegal mining.

“Ahmed is dead and we are still doing the hard-punching stories”, he said. “It is a testimony that Ghana definitely will remain the beacon of democracy. People are strong-willed. People challenge government. And that is what is the future of democracy.”

Although Hussein-Suale’s death was a “momentous shock”, Anas and his team are resolute.

“Out of the pain of his death, we are energized to leave a lasting impression for his memory, and tell things as they are. We are not deterred in any way. We are confident. We have the capacity to do even more than we used to do.”