This article is part of a series published by IPI exploring the role of media owners with cross-sectoral business interests in shaping the media landscape in Central and Eastern Europe. This includes examining the relationship of their business interests to the state and implications of their involvement in the media sector for independent journalism. This series is part of IPI’s work researching the phenomenon of media capture in the region. The present article profiles Serbian media owner Igor Žeželj, whose pro-government media holdings reflect the system of mutual dependency between the Serbian state and certain media owners.

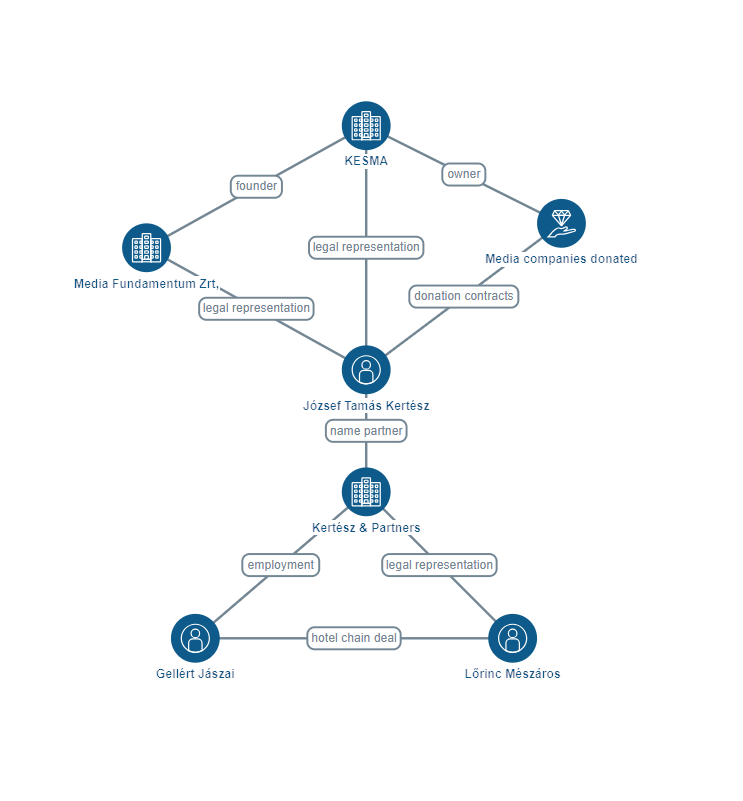

On a Wednesday morning in November 2018, Hungarian lawyer József Tamás Kertész was hard at work, emailing away. Before noon, Kertész, of the firm Kertész & Partners, had filed eight sets of documents at various Hungarian company courts. These bundles attested that the owners of eight different companies involved in the media sector had decided to donate their television stations, radio channels, newspapers, and news sites to a newly established entity: the Central European Press and Media Foundation, or KESMA.

KESMA was soon to become the centralized media hub for media aligned with Fidesz, the party of Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán. It would provide a vessel for the government to exercise indirect control over much of Hungary’s private media landscape.

Kertész played an important role in establishing KESMA, including filing the company’s registration papers earlier in 2018. He had long enjoyed close relations to Fidesz and its allies, including acting on the sale of a hotel chain to top oligarch Lőrinc Mészáros. By that time, Mészáros – a childhood friend of Orbán – had come to prominence among the ranks of pro-Fidesz businessmen vying to fill the vacuum left by Orban’s former key ally, Lajos Simicska. More on this below.

In December of 2018, the Orbán government decreed the formation of the KESMA conglomerate a matter of “strategic national importance”, thereby enabling KESMA to evade an investigation by the competition authority over antitrust rules.

By then, an investigation by a Hungarian news outlet estimated that KESMA controlled close to 500 media outlets. But who were the people who donated them to the conglomerate, and how did they come to own them in the first place?

Image 1: Establishing KESMA

Friends of Orbán

The donations to KESMA came from several media owners, all of whom have had close ties to Fidesz. Many were new investors in the sector, since previously most party-aligned media ventures were centred around Simicska. In the 1990s, Simicska served as Fidesz treasurer and is credited with creating the original business blueprint for a pro-Fidesz empire, and also controlled party-aligned media ventures. Orban and Simicska fell out in 2014-2015.

After the falling out, Orbán called on wealthy Fidesz supporters to get involved in the sector during a televised interview.

“I am encouraging everyone – this cannot be a task for the government, but I am encouraging our political community – Fidesz people and Christian Democrats, our adherents and our people who cooperate and agree with us, to put energy into this, both personal and financial, and make it happen”, Orbán said.

In the interview, he cited Gábor Liszkay as a positive example. Liszkay was one of the most important people involved in operating the party-aligned media machinery in the Simicska era. Liszkay’s 2015 resignation from leadership roles at the daily Magyar Nemzet and Hir TV blew open the feud between Orbán and Simicska, with Simicska accusing Liszkay of betrayal and doing Orban’s bidding. The very public row sealed Simicska’s fall from grace, providing an opportunity for others to fill his role.

While the real control belonged to Simicska, Liszkay had held large numbers of shares in the media companies, including a nominal majority of Magyar Nemzet. Simicska paid Liszkay some €260,000 (a fraction of the real value) for his shares after Liszkay’s resignation and it is thought that this money provided the initial capital for Liszkay to purchase the economic daily Napi Gazdaság. He renamed it Magyar Idők and repurposed it as a general newspaper. The investments needed for this received a boost when János Sánta, president of Continental – a tobacco trader that enjoys a practical monopoly on the Hungarian market thanks to legislation introduced by Fidesz – joined Liszkay as part owner.

In 2018, Lőrinc Mészáros bought Magyar Idők and integrated the daily into the company Mediaworks. The purchase was facilitated by the fact that Mészáros had appointed Liszkay as CEO and president of Mediaworks two years earlier shortly after Mediaworks had been bought by two Seychelles-registered companies, believed to be controlled by Mészáros in late 2016. Mediaworks would later become the largest company at the heart of KESMA.

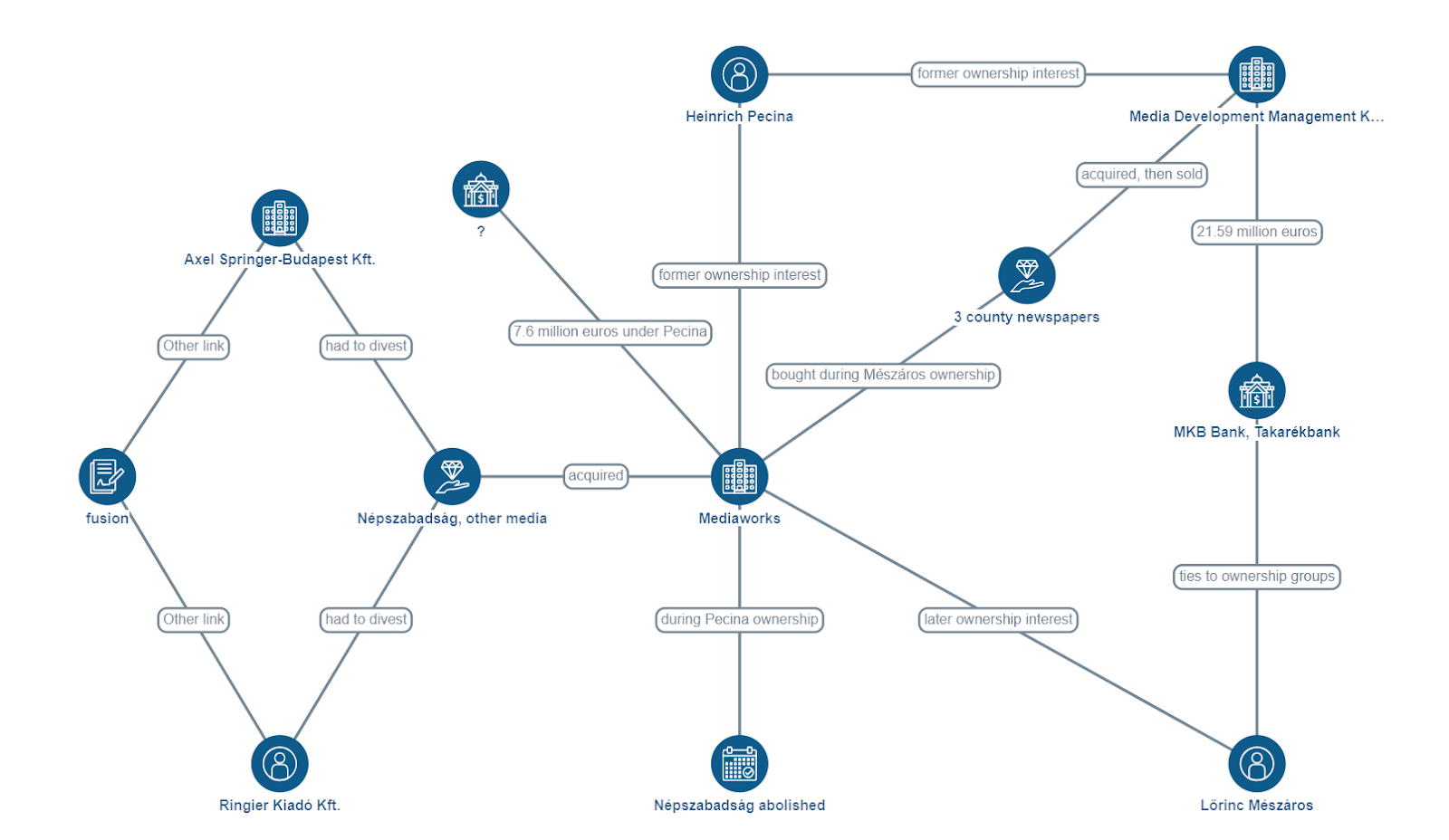

Image 2: Liszkay creates Magyar Idok, with help from tobacco magnate Janos Santa, before selling to Mediaworks

Mediaworks, Mészáros, and a media purchasing spree

Mediaworks started in late 2014 when Austrian businessman Heinrich Pecina bought the newspapers that media giants Ringier and Axel Springer had to divest in order for the Hungarian competition authority to greenlight their merger. Under Pecina’s leadership, Mediaworks abolished the 60-year-old left-wing Népszabadság, at the time the most-read daily newspaper in Hungary. Mediaworks was then sold to Mészáros.

Mediaworks took out loans worth €7.6 million to finance the initial acquisition of these newspapers but the lender remains unknown.

With Mészáros at the helm, Mediaworks bought up most of the local daily newspapers (and their online versions), which were often unchallenged leaders in their respective markets. This control of the local media sector enabled Mediaworks to replicate content on the cheap, such as when on the day before general elections in spring 2018, all local dailies published the same interview with Orbán, titled “Both votes for Fidesz”.

One such group of local dailies was first purchased by a Cyprus-registered company with ties to Pecina using €21.59 million in loans, about 80 per cent of the price, provided by MKB Bank and Takarékbank. At the time, MKB had just been privatized to an opaque group of investors, while Takarékbank was in the process of being pieced together from savings cooperatives, and under the legislative control of the Fidesz-dominated parliament. The ownership groups behind both banks had ties to Mészáros’s circle. The three local dailies were then sold to Mediaworks.

Mészáros also bought Echo TV, the broadcaster on whose programme Orbán initially demanded Fidesz allies to buy up the media, and then donated it to KESMA.

Notably, immense public procurement tenders won by Mészáros’s other companies helped him to be the main actor in the buying up of media on behalf of Fidesz. Between 2018 and 2020, Mészáros’s companies – mostly in the construction business – were calculated to have won government tenders amounting to €1.67 billion, or seven per cent of all tenders. (According to an earlier calculation, 83 per cent of tenders won either by him or his family members were financed from EU funds and half of the tenders were not subject to open competition). The former small business owner has enjoyed a meteoric rise to the top of Hungary’s rich list in 2021 and in 2023 had an estimated worth of 660 billion HUF (1.67 billion euros).

Image 3: Mediaworks purchases media formerly owned by Ringier and Axel Springer, via Heinrich Pecina, financed by MKB Bank and Takarekbank. Hungary’s most popular left-of-centre newspaper Nepszabadsag, closed in the process.

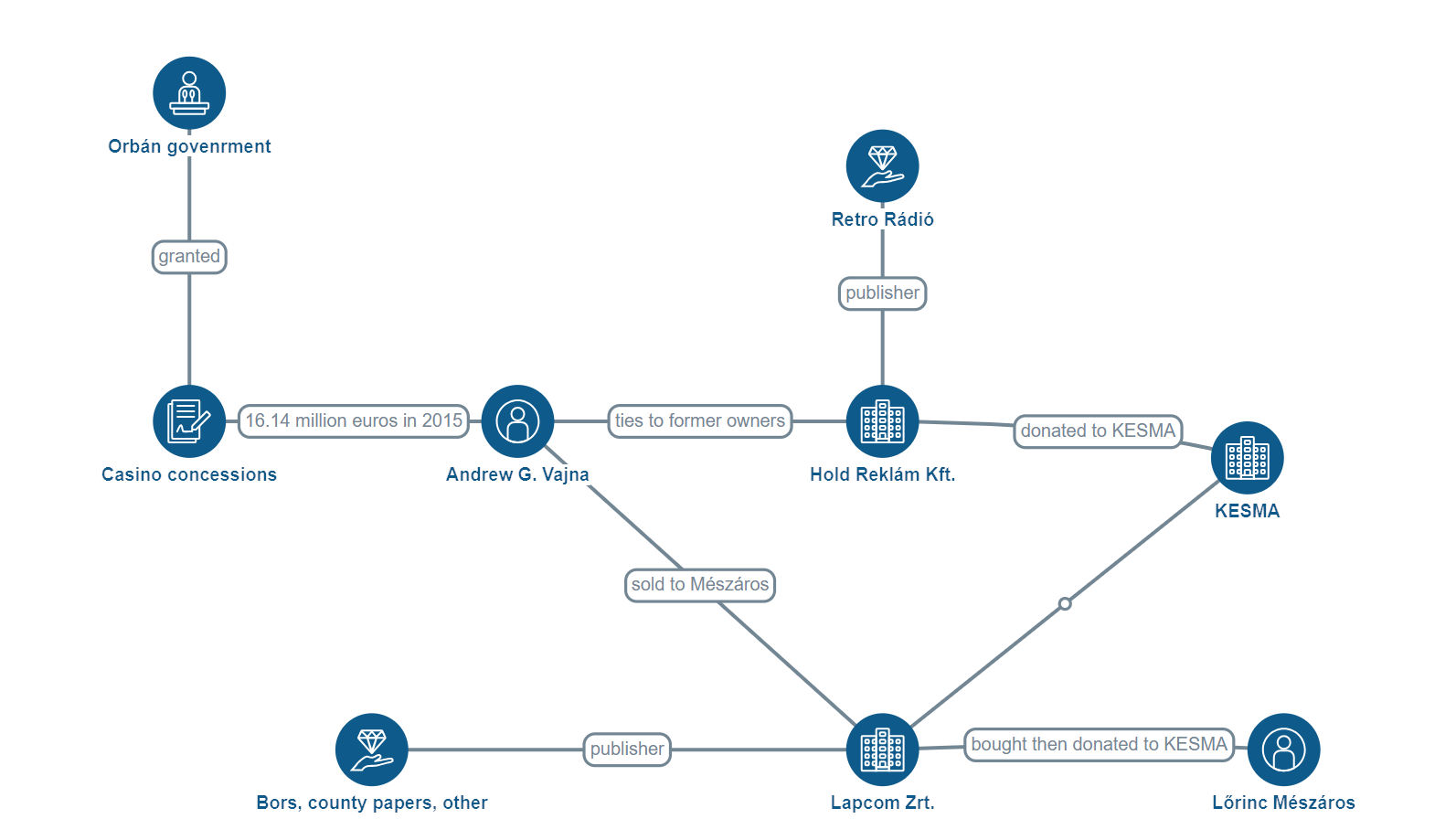

The Hollywood producer: Andrew G. Vajna

Other businesspeople also acquired media after the Orbán interview in Echo TV, only to later hand them over to KESMA. They include the late Andrew G. Vajna, who emigrated to the U.S. as a child, and after a successful career as film producer, returned to his native Hungary as a government commissioner for film industry financing. Vajna’s business fortunes received a sizable boost in 2014 after his interests were awarded several casino concessions in Budapest. The next year, these casinos made Vajna €16.14 million.

Before his death in 2019, Vajna also made acquisitions in radio and television, but only donated a company holding the tabloid Bors, several local newspapers and a score of smaller print publications to KESMA. (Technically, Mészáros first acquired the company from Vajna for an unknown sum and was the one to donate it to KESMA, but Vajna is believed to have realized a loss on the transaction). In addition, Vajna had ties to the publisher of profitable music broadcaster Retró Rádió, which was also donated to KESMA.

Image 4: Andrew Vajna, film producer turned casino king, turned media investor

Origo and the national bank

Origo, one of the most-read online news sites in Hungary, became the online news centrepiece of KESMA after it was donated by Ádám Matolcsy, the son of Hungarian National Bank (HNB) governor György Matolcsy, a close ally of Orbán. Matolcsy purchased New Wave Media Group, which owned Origo, in November 2018 only to donate it to KESMA the following month. Matolcsy enjoyed close financial ties to the owner of the NHB Growth Credit Bank, Tamás Szemerey, who is also his father’s cousin.

Origo’s acquisition by New Wave in late 2015 was financed by a loan worth €11.06 million by MKB Bank, which was at the time being restructured by the state and effectively controlled by the HNB. Szemerey’s own bank, NHB Growth Credit Bank, also provided a sizable loan – with very favourable conditions, made possible under the HNB’s national quantitative easing programme – to New Wave’s sister company. (NHB Growth Credit Bank, which dealt extensively with Szemerey’s acquaintances, failed in 2019).

Image 5: The financing of KESMA’s online-news centerpiece, Origo

Maria Schmidt and the Fidesz Figyelő fist

The weekly Figyelő was donated to KESMA by the family holding company of Mária Schmidt. (Schmidt’s son Péter Ungár, president of opposition party LMP also owns a large stake). Schmidt, who is independently wealthy, has various dealings with the state through her investments in real estate. She is also managing director of state-founded KKETTK, an organization spending government funds on history-oriented projects, such as House of Fates, a divisive memorial to Holocaust victims.

Formerly a business weekly, Figyelő was repurposed under Schmidt’s watch. In 2018, the weekly published a list of people deemed to be “mercenaries” of George Soros, the Hungarian-American investor and philanthropist of Jewish background and frequent target of conspiracy theories and smear campaigns. This list was later found by a Hungarian court to be part of a political campaign against NGOs.

Other people who donated media holdings to KESMA include Árpád Habony (an unofficial advisor to Orbán), Tibor Győri (a former state secretary under Orbán), András Tombor (a former national security advisor to Orbán) and Péter Schatz (a former executive at national broadcaster MTVA, who was also involved in Slovenian media investments).

Media holdings formerly held by Lajos Simicska, who had thrown in the towel in his conflict with Orbán, were also gifted to the conglomerate. KESMA then promptly folded the daily Magyar Idők and the broadcaster Echo TV into the longtime right-wing brands Magyar Nemzet and Hír TV.

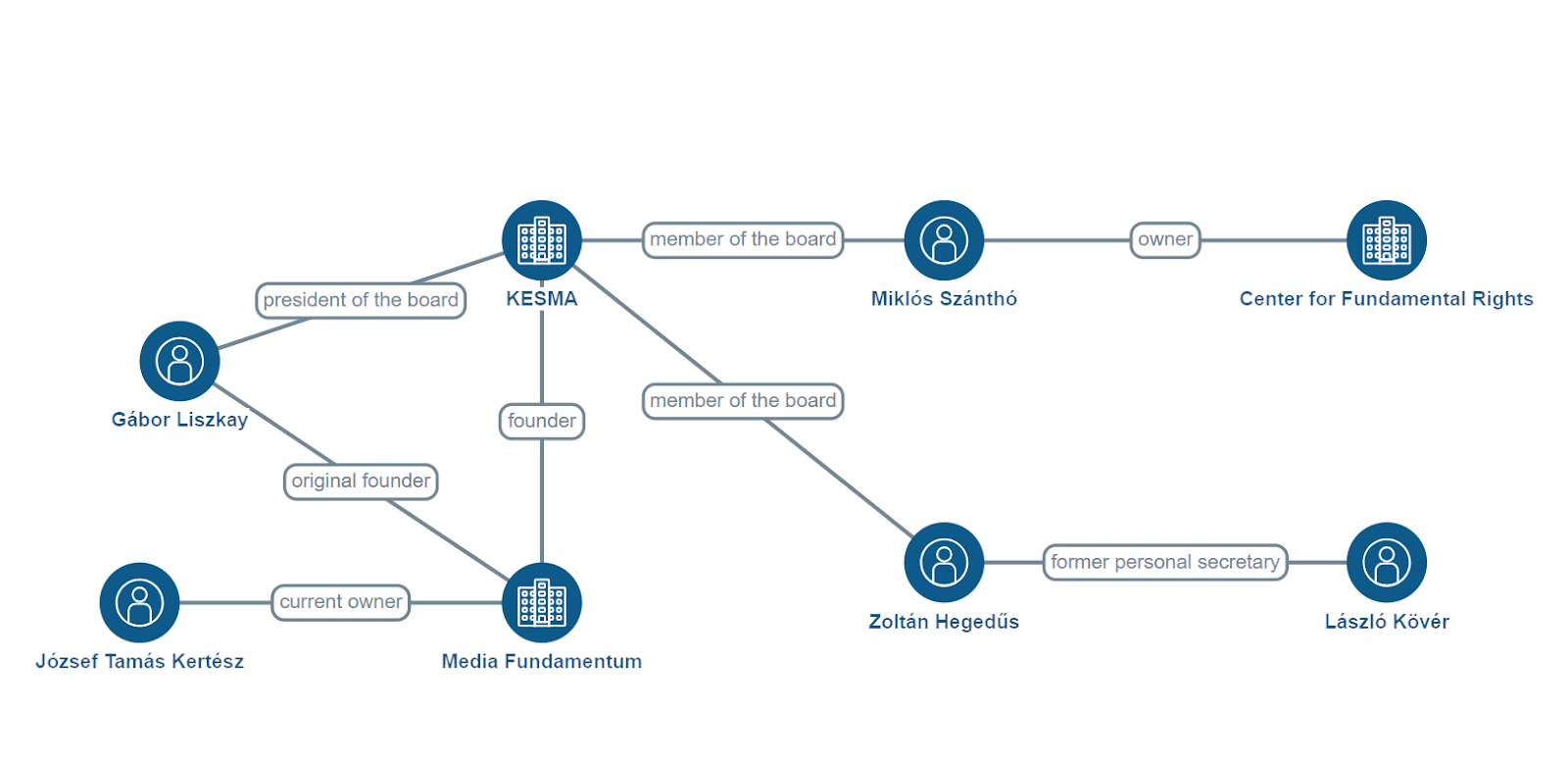

Control and finances of KESMA

Overall control – the right to appoint and withdraw board members – of KESMA lies with its founder, the company Media Fundamentum. At its inception, Media Fundamentum was owned and headed by Gábor Liszkay. In 2020, Liszkay retired and was awarded, on Orbán’s initiative, the Commander’s Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit for establishing and leading “Christian, patriotic” media organizations. He then sold his stake in Media Fundamentum to József Tamás Kertész, the lawyer who drafted the company’s original founding articles.

Image 6: KESMA connections

Liszkay came out of retirement in 2022 to be appointed president of the board at KESMA. Other board members are Miklós Szánthó, who also heads the Fidesz-allied think-tank Center for Fundamental Rights, and Zoltán Hegedűs, a former personal secretary to prominent Fidesz politician László Kövér.

The establishment of KESMA couldn’t have happened without Orbán’s wealthy allies who heeded the call to invest in media, and did so using the profits they had made through lucrative state contracts and favourable banking loans. Once established, the conglomerate hasn’t needed fresh capital to finance its operations thanks to highly profitable advertising arrangements.

Government spending on advertising was already showing signs of state capture in the Simicska era. Between 2010-14, almost half of all public communication contracts went to one applicant or were awarded without a formal competition. Both the public officials issuing advertising services and the agencies winning the tenders had ties to Fidesz’s economic allies and in the end, more than half of all state advertising ended up at Fidesz-allied media.

During the standoff between Orbán and Simicska, state advertising funds were channeled to the budding media companies owned by Orbán’s allies. When KESMA came to life, its first yearly financial report said it consolidated companies worth altogether €21.9 million, with an overall profit of more than €36.7 million. In other words, the companies involved posted a return-on-net-assets ratio of 144 per cent for the first year of KESMA – an absurdly huge number, especially for an organization mainly involved in legacy media ventures in 2018.

Hungarian NGO Mérték Média Monitor calculated that government advertising funds totalled about 365 million euros (without discounts) in 2020 and that 37 per cent of these funds were spent at companies belonging to KESMA while a further 49 per cent went to the public broadcaster and other pro-government outlets. State advertising revenues comprised close to 90 per cent of all revenues at several well-known media.

Income from government advertising has proven so successful in keeping government-aligned media afloat that some of these media are now being closed down reportedly not for being unprofitable, but for being too wasteful with the cash channeled to them from elsewhere.

Despite KESMA reporting €28.16 million in profits during the 2022 election year, after Fidesz’s return to power the organization implemented a serious downsizing at several of its papers. The print editions of Figyelő, the daily Magyar Hírlap and the economic daily Világgazdaság were closed, while far-right news site 888 was folded into Origo in 2023. Large state advertisers concurrently significantly decreased their spending.

According to Mérték, government advertising dropped to €232 million (without discounts) for the year 2022. Numbers for different years are not outright comparable, but state advertising seems to have contracted by at least 20 per cent over two years. The trend suggests that instead of legacy media, Orbán has shifted his focus to digital-first players, such as the Megafon stable of political influencers. Fidesz-friendly Influencers with Megafon spend millions of euros at Facebook to advertise their videos to users, while the source of the company’s income, worth €7.1 million in 2022, is unknown.

Conclusion

While KESMA is formally independent of the Fidesz party and Orbán’s government, the handprints of the Hungarian prime minister are all over its creation. Orbán was smart enough to understand how the optics of direct government meddling in the media would look – the rebuilding of party-allied media “cannot be a task of government”, he said – and he left the task of collecting media to his “allies and adherents”.

Orbán’s supporters turned to the assets of their respective areas of operation – e.g., Mészáros to his wealth accumulated in the construction industry, including through state contracts – to complete their assignment. Moreover, their decision to give up their holdings freely to the KESMA foundation further illustrates how their wealth and influence remain dependent on the good will of the prime minister.

Pumping money into pro-government media creates enormous economic barriers to its independent competitors, denying them access to both state and subsequently also private corporate funds. The financial precarity of independent media is also exacerbated by the sizable viewership and readership that, largely out of habit, remain with the numerous, formerly reputable media brands taken over by pro-government interests, such as Origo and Index. On the other hand, the recent proliferation of independent media companies founded by editors and journalists who left their former jobs after pro-government takeovers means that independent media may now have a better structural foundation necessary to withstand politically motivated takeover attempts if financial stability can be assured.

This series on the impact of media owners with cross-sectoral business interests on the media landscape in Central and Eastern Europe is supported with funding from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF).