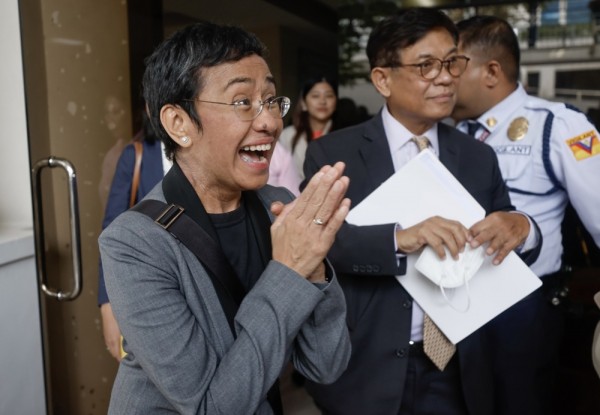

This week’s criminal conviction of IPI Executive Board member Maria Ressa of the Philippines online news site Rappler and former Rappler writer Reynaldo Santos Jr threatens to see journalists jailed while chilling new voices around the region.

Across the Asia-Pacific region, new digital media like Rappler have been bringing a critical overlay of accountability journalism. It’s been fresh, challenging and provocative. It’s been renewing journalism. Now, as the Rappler case shows, it’s being targeted by governments, often using bespoke cyber crime laws.

The Philippines Trial Court decision on Monday has already been widely condemned, including by the International Press Institute (IPI).

“Maria Ressa has been convicted for her fearless journalism and speaking truth to power. This ruling serves as a warning to all independent journalists in the country”, IPI Board chair Markus Spillmann said.

Ressa, Santos and Rappler were indicted for “cyberlibel” in 2017 under the 2012 Cybercrime Prevention Act. The story was originally published five years earlier, before the law came into effect. (The court ruled that corrections to punctuation in 2014 amounted to a re-publication.)

Both Ressa and Rappler have been targeted by the country’s president, Rodrigo Duterte, and his allies, particularly since he was elected in 2016. It started with online attacks and social media trolling, building to arrests and other forms of legal harassment. On top of this week’s cyberlibel conviction (which Rappler and Santos are appealing), Ressa and Rappler face eight pending cases, ranging from tax laws to foreign ownership rules. In total, Ressa faces nearly 100 years in jail.

Rappler is the major example of how the Asia-Pacific region’s emerging digital media is bearing the brunt of media freedom violations, which are increasingly being inspired by (or hidden behind) the emergency response to Covid-19. Even before the pandemic, governments had been taking legitimate concerns about “fake news” online to give themselves new powers — or repurpose old powers — to crack down on journalism and public commentary.

Here’s a particularly shocking example: Sovann Rithy of the Cambodian online news platform TVFB is in jail for posting on his personal Facebook page public quotes from Prime Minister Hun Sen, including: “If motorbike-taxi drivers go bankrupt, sell your motorbikes for spending money. The government does not have the ability to help.”

Cambodian authorities said Hun Sen was joking and Rithy was arrested for “incitement to cause chaos and harm social security”, which carries a prison sentence up to two years and a fine of up to four million riels (€900).

In India, Siddharth Varadarajan, founding editor of Indian news site The Wire, has been charged with “spreading panic”. In the context of attacks on Muslims after participants at a religious gathering in Delhi spread the virus, Varadarajan tweeted a reminder that large Hindu gatherings were held or planned even after the lockdown was announced.

The IPI Tracker on media freedom violations related to Covid-19 (there are currently 338 cases world-wide) has create a specific category of excessive regulation of fake news, such as Thailand’s time-limited emergency decree in March that made it a crime to share “misinformation” on-line about the virus or a new law in the Philippines imposing prison of two months or fines up to about $US19,500 for spreading “fake news” about Covid-19. (It’s already been used against an online news portal.)

In Singapore, the government used its Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act passed last October to order New Naratif to take down a story that, ironically, was seeking to explain how the law works.

Governments have been restricting access to information for online media. Again, in The Philippines, the emergency regulations block independent (usually digital) media from covering official briefings on Covid-19 in the country. They can submit questions beforehand and watch by video conference, but cannot seek clarification afterwards.

Put together in one place (and these are just examples), the constraints show how governments are intensifying their actions to bring journalism to heel, particularly the independent, questioning journalism of the new digital media.

This story was also published on Crikey.