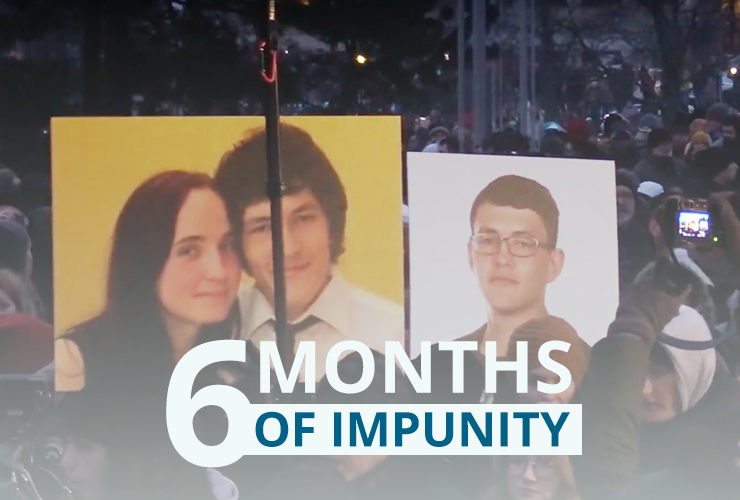

Six months ago today, Slovakia saw its first murder of a journalist since the country’s independence in 1993. Ján Kuciak, an investigative journalist investigating high-level corruption cases, was brutally murdered alongside his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, sending shockwaves through Slovak society.

Though officials have neither confirmed the motive nor identified the murderers, it is known that Kuciak was investigating links between the ‘Ndrangheta crime syndicate and top Slovak politicians. Having uncovered that Italian businessmen with links to organized crime had been laundering EU funds intended as development assistance, and having previously published evidence of tax fraud involving several businessmen close to the governing Smer-SD party, Kuciak clearly made the ruling elite uncomfortable.

But a murder bearing all the hallmarks of a contract killing is not the response anybody expected in Slovakia in 2018.

Token changes

“We have a police president who had connections to the mafia – this is very toxic”

Whilst the initial reaction – mass protests across Slovakia leading to the resignation of former Prime Minister Robert Fico and his cabinet – gave the impression that change was on the way, six months on, little progress has been made. The police investigation is ongoing, but to date, no arrests have been made. Indeed, many Slovaks suspect that the government changes since Kuciak’s murder amount to nothing more than a facade, with the strings still being pulled by the same characters.

Denisa Saková took over the post of interior minister from her former boss, Robert Kalinak, in a move seen by many as the cynical continuation of the previous government’s corruption. Worse still, the new chief of police has alleged links to organized crime and to the very mafia which is believed to be behind the murders of Kuciak and Kušnírová. This makes it hard for many in Slovakia’s journalistic community to take the investigation seriously.

“We have a police president who had connections to the mafia – this is very toxic”, Peter Bárdy, editor-in-chief of the news site Aktuality.sk, where Kuciak worked, told the International Press Institute (IPI). “And the same people are in control as before.”

Unsurprisingly, those campaigning for a “clean” Slovakia have been left underwhelmed. After all, the case of Kuciak’s murder remains far from solved.

Taking a leaf from Viktor Orbán’s book

“Slovaks think our country is under attack from some power from abroad”

Many hoped that after the tragic killings the government would develop a more constructive relationship with the media. Indeed, in the days immediately after Kuciak’s murder, promises of change abounded. It was almost as if Slovakia were about to enter a new era of unmitigated press freedom.

Six months later, few changes have materialized. If anything, the government and ruling party officials, including the still-influential Fico, have been borrowing from none other than Europe’s resident expert in anti-media rhetoric: Viktor Orbán, prime minister of neighbouring Hungary.

“Slovaks think our country is under attack from some power from abroad”, Bárdy explained. “Fico has said many times that George Soros is responsible for the problems in Slovakia. He’s using the same policy as Viktor Orbán and these tactics are working.”

Transparency is also a problem: Journalists seeking information about the murder investigation from the Interior Ministry say they’re lucky to receive a reply within a few days. And when there is a chance that information damaging to the governing Smer-SD party could be revealed, there is simply no cooperation from the ministry.

Unanswered questions

“If anyone hopes that Ján Kuciak and the murder will sink into oblivion, they are terribly wrong. We will keep asking questions and we will keep reminding the public that the murder of a journalist is an alarming red line in a society.”

“For the first three months after the murder, there was a huge movement”, Bárdy said. “But now the demonstrations have stopped.”

Journalists and editors in the country are concerned that as momentum for change slows, the likelihood that Kuciak’s killers will escape with impunity grows. And despite the anti-government protests, opinion polls suggest that Smer-SD would win enough votes to remain in power, though it is far from clear whether a change in government would improve the current situation.

“We still do not know who killed our colleague and why, and the police are tight-lipped when it comes to information about the course of investigation”, Beata Balogová, editor-in-chief of Slovakia’s leading quality daily SME and a member of IPI’s Executive Board, pointed out.

But she added: “If anyone hopes that Ján Kuciak and the murder will sink into oblivion, they are terribly wrong. We will keep asking questions and we will keep reminding the public that the murder of a journalist is an alarming red line in a society.”

It is critical for Slovakia’s journalistic community that the numerous questions behind Kuciak’s murder be answered: Who is responsible? Who, if anyone, in the government is linked to the murder? Is there a link between some officials’ anti-media rhetoric and the killing?

Only once these questions are answered can there be real justice for Kuciak and the safety of investigative journalists in Slovakia secured.

[content_boxes layout=”clean-horizontal” columns=”1″ icon_align=”left” title_size=”24″ backgroundcolor=”#e6eef0″ icon_circle=”” icon_circle_radius=”” iconcolor=”#e6eef0″ circlecolor=”#e6eef0″ circlebordercolor=”#e6eef0″ circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”#e6eef0″ outercirclebordercolorsize=”” icon_size=”” link_type=”” link_area=”” animation_delay=”” animation_offset=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ margin_top=”0″ margin_bottom=”0″ class=”” id=””]

[content_box title=”” icon=”” backgroundcolor=”#e6eef0″ iconcolor=”#000000″ circlecolor=”#98cbb8″ circlebordercolor=”” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” iconrotate=”” iconspin=”no” image=”” image_width=”35″ image_height=”35″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

We will not allow Ján and Martina to be forgotten

Statement from Slovak journalists half a year after the murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová

It has been half a year since our colleague, Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, were killed. We still do not know who killed them and why they did it. We still have our doubts about the independence of the investigation. Ján also wrote about the mafia who had contacts with people very close to the former prime minister Robert Fico. Since there have not been fundamental changes to the police or to the prosecutorial bodies after the murder, we can hardly have much trust in the real investigation.

The murder of our colleague shook us, but it did not scare us. We did not stop asking, investigating, and monitoring politicians and people in public office. Ruling politicians have not changed after the murder. The language they use when talking to and about journalists is even harsher now. They even link the murder and the reaction it provoked with conspiracy theories.

Independent journalists are essential for a democratic country. Let us not forget this half a year after the murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová.

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]