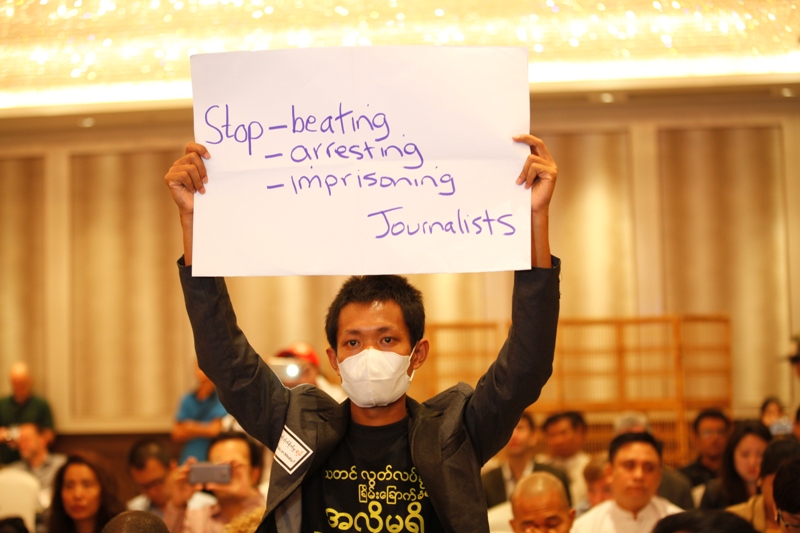

Myanmar journalist Soe Yarzar Tun stood up from the crowd wearing a mask and holding a placard reading “Stop beating, arresting, imprisoning journalists”, interrupting Myanmar Information Minister Ye Htut as he spoke.

It was March 27 – just one month ago – and the information minister was speaking at the first day of the International Press Institute (IPI)’s 2015 World Congress in Yangon. Earlier that month, on March 10, three journalists were beaten in a student protest in Letpadan. Two others were detained. Soe Yarzar Tun was saying that Letpadan’s events could not be allowed to be repeated.

The daring act left many of those present concerned about the repercussions the journalist could face. Myanmar’s peaceful assembly law, which has drawn international criticism, requires, among others, for chants to be identified in advance of a protest.

Internationally renowned Myanmar journalist, Aye Aye Win, a correspondent for the Associated Press, said that no actions were taken against the journalist holding the placard or several other journalists protesting against the government outside IPI’s World Congress.

Information Minister U Ye Htut even argued at the World Congress that Soe Yarzar Tun’s protest was “another sign of how much Myanmar is changing”.

Aye Aye Win told IPI that “no major developments [threatening media freedom] have taken place since [the] March Congress”. However, she noted, another journalist who staged a protest last year calling for media freedom was charged under “section 18 of [the] controversial peaceful assembly law on April 24” and ordered to pay a fine of 20,000 kyats (approx. €17).

“His punishment seems lenient compared to others who were given between two to six months in prison under the same charge”, Win said. “But the fact that a journalist who protests against suppression of journalists is charged under the peaceful assembly law is not a positive sign.”

There were some additional, and unusual, worrying sings. U Thiha Saw, veteran editorial director at the Myanmar Times and a member of Myanmar’s interim Press Council, described “a couple of incidents” with some impact on media freedom.

“For the first time ever, the military came up with a so-called the Military Information Team (for correct news) and criticized two newspapers for their contents”, he told IPI. “The first one was against the Myanmar Times weekly [in late March] for one of its cartoons [about a military offensive in Kokang province], which the military presumed was against their operations in the northeast and said they ‘felt sadness and felt that the military had been defamed’. The second [which came just days ago] was against a daily newspaper, the Eleven Daily, for its story about the same operation involved in Kokang area.”

Eleven Daily recently apologised for publishing an image said to show government forces captured by rebels without blurring the soldiers’ faces, but it rejected accusations that a report it published about heavy government casualties violated journalistic ethics.

Kokang province, on Myanmar’s north-eastern border with China, has seen continuing turmoil between government forces and local ethnic insurgents since Feb. 9.

“The media community felt those kinds of ‘statements’ by the military in the state-owned newspapers are indirect intimidation against the local private media and a threat to the freedom of press”, U Thiha Saw said. “The Press Council has been pushing the military, for quite some time, especially their media arm with a draconian name – Military Public Relations and Psychology Warfare Department, which is headed by a brigadier general – to come up with an information team to respond to our queries. They never listened seriously to us.

“Finally, they came up with this idea of the Military Information Team (for correct news). The letters in parentheses are literally there in the name. We don’t know when it was created, but it was the first time we ever heard when they first came up with a statement against the Myanmar Times.”

Nay Phone Latt, a former political prisoner and award-winning writer, told IPI that in comparison with the Military Regime – prior to 2011 – there currently exists some degree of freedom of expression.

“But the freedom we get has limitations and we still have the untouchable zones,” he said. “If some journals and journalists touch the untouchable zones, they can get into trouble anytime.”

Twelve journalists are in prison in Myanmar in relation to their reports on the military or government officials, or their coverage of protests; three of them are serving a seven-year sentence.

“There is no change of the status of journalists in prisons”, Aye Aye Win said. “Their appeal process has not been successful so far”. She added that the “investigations are not going anywhere and no one is held accountable for the death of the journalist [Aung Kyaw Naing] in military custody nor for beatings by government-hired thugs against journalists.”

Dr. Thida Tin, deputy director general at the information department of the Ministry of Information, said that the journalists in prison have a right to appeal to the superior court. “Before the law, everyone will be treated equally and not (according to) occupation, status, rank, and races, gender and etc”, she told IPI.

Aung Kyaw Naing was killed on Oct. 4, 2014 after he was detained by the military while covering violent clashes between the military and a rebel group, the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), near the border with Thailand. When his body was exhumed, it was revealed that he suffered a cracked skull, broken ribs and a broken arm, and was shot five times. A national commission has recommended that the matter be brought before a civilian court.

U Thiha Saw said that the Press Council asked the military’s commander-in-chief to directly investigate the death. “There has been an attempt to file a law suit against the military unit concerned,” he said. “The case was turned down initially, but later on the township court said they will accept the filing.”

With respect to the beatings of journalists in Letpadan in March, some reports indicated that hired thugs were involved in the incident. U Thiha Saw said that the Press Council issued statements against the events. He also noted that one member of the Press Council, the Myanmar Journalists Network (MJN), announced that they would be filing a legal case against the Ministry of Home Affairs, which is responsible for the police force.

However, again, according to Aye Aye Win, no investigation has started regarding the beatings and detentions of journalists and students during the protest.

Many observers told IPI that they fear the circumstances surrounding media might deteriorate as journalists prepare to cover the first-ever competitive general election, scheduled for October.

Dr. Thida Tin noted that the Press Council has drafted a code of conduct on election reporting. According to her, there is a large degree of cooperation between Press Council and the media. “So, media outlets will understand how to cover pre- and post-election,” she said.

Further, U Thiha Saw said that some media outlets have already started the process of election reporting and some others are preparing trainings for journalists in covering elections and campaigns.

Yet Aye Aye Win said that “in the view of recent suppression against journalists, there are concerns that the media might face difficulties during election coverage especially in districts where local authorities tend to abuse their administrative powers in their respective regions”.

Nay Phone Latt drew attention to media ownership as another potential obstacle to media freedom.

“In the Military Regime, the way to tackle the media was by shutting down and censoring them”, he said. “Now, the so-called democratic government, which comes from the Military Regime, changed its approach. They let the media outlets grow in the boundary they set and they try to distort the media landscape by using state-owned and crony-owned media.

“There was the saying by one minister ‘attack the media with the media’. So before the election, the media will take the big role and also that kind of colourful media will try to manipulate the media landscape.”

The Press Council was set up with the intention of dealing with such concerns. According to U Thiha Saw, the Press Council has received more than 100 complaints raised “from all directions”. The most recent case was a complaint by the military against a daily newspaper, he noted.

Nay Phone Latt said that the Press Council still has not established a clear role. “They just focus on the media and journalists to be ethical, but they forget to stand with the media and protect the journalists”, he told IPI.

But U Thiha Saw argued that acceptance of the Press Council by local media was, at best, mixed. “There still are some media who refuse to cooperate (with the council), but more and more government departments, including the military, and media houses have trust in the Press Council’s role,” he observed.

And it seems that this trust cannot be extensively established without major legislative improvements. In a joint submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Myanmar by the U.N. Human Rights Council dated March 23, 2015, ARTICLE 19, the Myanmar Journalists’ Association (MJA), the Myanmar Journalists’ Network (MJN) and the Myanmar Journalists’ Union (MJU) recommended that the government amend, among others, its News Media Law so that its primary purpose is the protection of media freedom and the freedom of expression.

The groups also called for the establishment of bylaws ensuring that the Press Council is independent from the government; the decriminalisation of defamation and sedition; the removal of licensing regimes for the printed press and of illegitimate content restrictions; an end to government ownership in print media and the establishment of independent public service media; and for work towards a right to public information law.

Information Minister U Ye Htut said during IPI’s World Congress that Myanmar’s “reform process is irreversible”. Yet a month later a government representative could not cite any specific action that has been taken in regard to legislative reform.

U Thiha Saw, when asked whether there were any positive developments in relation to media legislation changes, commented: “I have to say, not much recently.”

He continued: “The major issues with the regulations and legal framework in Myanmar media are two-pronged. Firstly, the News Media Law which is supposed to protect the rights of journalists has been approved by the parliament, but the by-laws are still with the Attorney General’s office for approval. As a consequence, journalists could not enjoy the protection and rights provided by the News Media Law in full effect.

“Secondly, there still are many laws that are a threat to the working journalists. The sections in the Criminal Code and Electronic Transaction Act, the Official Secrets Act and a few others still need to be abolished or amended so that they no longer pose threats against the freedom of expression. The last time the Press Council had a meeting with the officials from the Ministry of Information and the attorneys from the Attorney General’s office to finalise the by-laws was in March. And we haven’t received any response from the AG’s office yet.”