Increasing censorship and a crackdown on press freedom across the globe have forced many journalists and media outlets into exile. Reporting from abroad brings a host of challenges, including security threats and difficulties reaching audiences back home.

The 2023 IPI World Congress and Media Innovation Festival brought together panelists representing publishers and media development organizations from Belarus, Poland, Afghanistan, South Africa, Myanmar, and Russia. They spoke about their experiences operating in exile and shared insights on how they continue to make a difference in spite of the challenges they face. The discussion was moderated by Joanna Krawczyk, deputy managing director, Geostrategy East, at the German Marshall Fund.

Crackdown in Eastern Europe

“Despite operating in exile, we have 3 million unique users per month and we have managed to make an impact”, Aliaksandra Pushkina, director of communications for the Belarusian news outlet Zerkalo, said. Zerkalo emerged after the Lukashenko regime shut down TUT.BY, the country’s most widely followed media platform, and detained several of its staff members, including Editor-in-Chief Marina Zolotova and CEO Lyudmila Chekina.

Following Lukashenko’s media crackdown in 2020, the Tut.by team found themselves forced to seek refuge in exile. They initially relocated to Kyiv, Ukraine, and later moved their operations to Vilnius, Lithuania, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine started. (Zerkalo was one of this year’s nominees for the IPI-IMS Media Free Media Pioneer award. You can read more about Zerkalo and other nominees here.)

In neighbouring Russia, as a consequence of the Kremlin’s harsh crackdown on independent media that accelerated in 2021, investigative outlet Istories was also forced into exile. This move came about after multiple media organizations, including IStories, were designated as “undesirable organizations”, rendering their operations within Russia impossible.

Currently based out of Prague, Istories continues to confront numerous challenges that range from persistent security threats and the complexities of collaborating with freelancers based in Russia to the constant blocking of their website. Nevertheless, IStories, committed to exposing Russian war crimes and corruption, reaches millions of Russian citizens, not just in major cities but also in the regions.

“Even clicking a like under our social media posts can potentially result in imprisonment for any of our readers”, Roman Anin, IStories’s editor-in-chief, said. “Reaching our audiences and collaborating with freelancers demands a great deal of creativity. Sometimes, I feel less like a journalist and more like a spy, working to gather information from Russia and unveil the truth to the world.”

Existential challenges

In Africa, too, a large number of journalists are operating outside of their home countries, Christoph Plate, director of the Media Programme Subsahara Africa at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, said. “There are many counties [in Africa] that make lives of the journalists who consider themselves as critical commentators and gatekeepers difficult and force many of them into exile.”

According to Plate, African journalists in exile face not only technical and existential challenges but also language barriers and the absence of essential resources. Due to political turbulence, journalists cannot be guaranteed to maintain their protected status in their host countries. For instance, Burundian journalists sought shelter in Rwanda while relations between the two countries were strained. However, after a rapprochement, the situation became unsettling for Burundian journalists in exile. Finances are always a hurdle for exile journalists. And, Plate added, many “feel disconnected from the discussions at home, not having a voice anymore”.

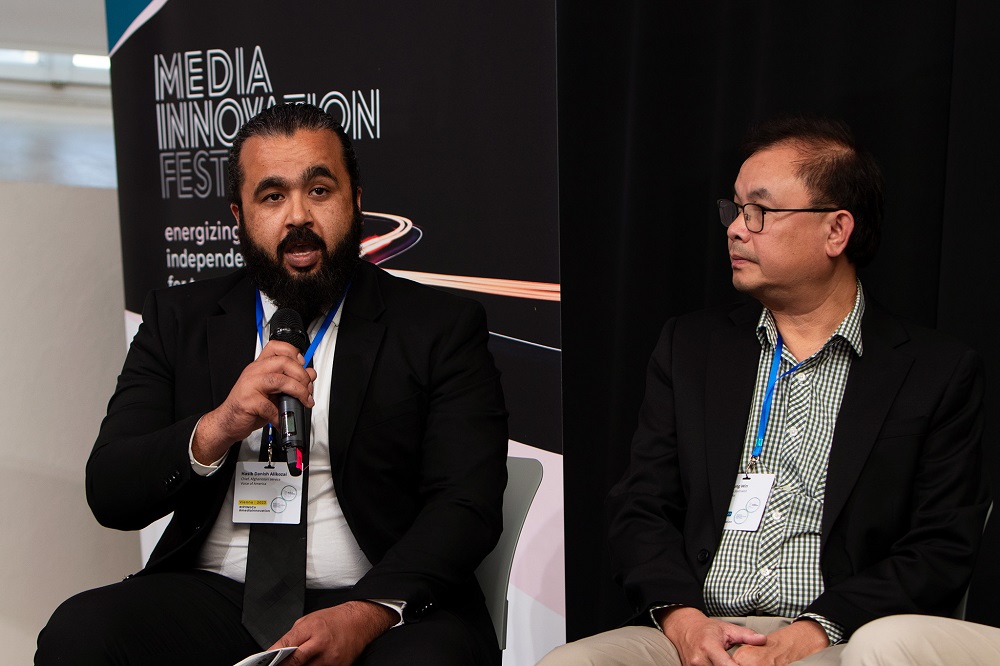

After the Taliban takeover in 2021, journalism became an extremely dangerous profession in Afghanistan. “The free media landscape shrunk entirely in the country. People are no longer able to hold those in power accountable. 7000 reporters, 70% of whom are women, lost their jobs,” Hasib Danish Alikozai, chief of the Afghanistan Service at Voice of America, said.

@VOAPashto and @VOADari chief @HasibAlikozai explains how VOA is tackling the challenge of having most of our Afghan reporters in exile in an #IPIWoCo panel. Watch live stream here https://t.co/yGScotuLsZ @globalfreemedia pic.twitter.com/ue09R37j27

— Ayesha Tanzeem (@atanzeem) May 25, 2023

But he added that the VOA Afghan service team was prepared to work under extraordinary circumstances in order to keep delivering truth to readers. “What worked for us was being proactive. We were aggressively promoting alternative frequencies months prior to the Taliban’s crackdown on media and introduced circumvention tools a year in advance”, he said.

Now, he noted, VOA Afghan service reaches 7.5 million people weekly and has 1.7 billion views on digital in total.

“You can not completely suffocate freedom of expression and free flow of information. People will find their aways around it”, Danish Alikozai said.

Diversifying to reach audiences at home

Working in exile is not new to Khin Maung Win, a veteran journalist and consultant for Myanmar’s Mizzima Media (a past recipient of IPI’s Free Media Pioneer award). He worked in exile as a journalist from 1992 until 2012, before returning to the country. But after the 2021 Myanmar coup d’état, he was once again forced to operate from abroad. “All the independent media relocated to safer areas…now we have to rely on satellite broadcast”, Khin Maung Win said.

Mizzima’s strategy involves diversifying its audience reach by utilizing various platforms. While satellite broadcasting remains their primary focus, they also engage with audiences through radio, their website, and social media channels.

WATCH THE RECORDING HERERevisit the IPI World Congress & Media Innovation Festival 2023