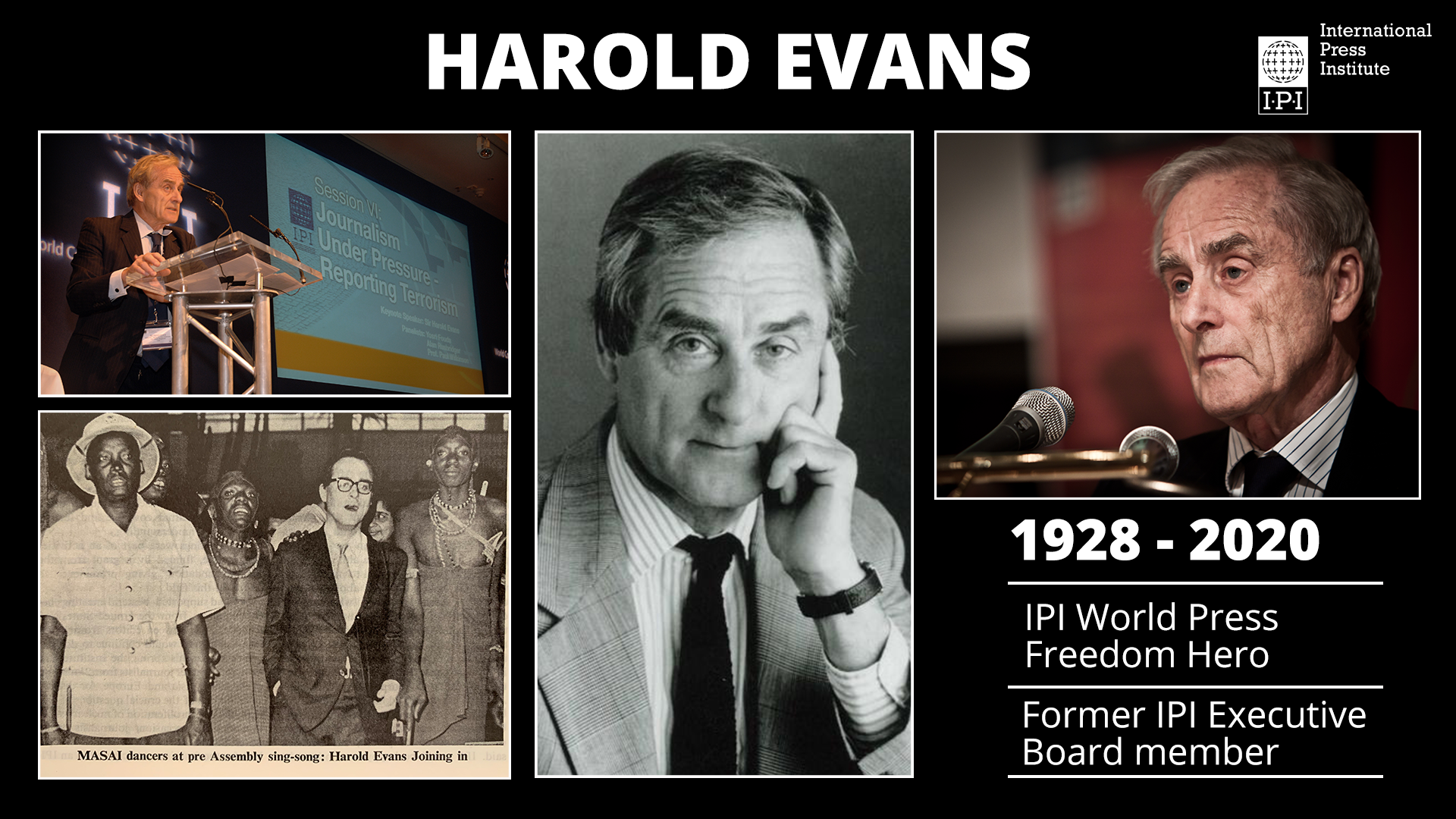

Harold Evans, former editor of The Sunday Times and Editor-at-Large of the Reuters, passed away on September 23, in New York. He was 92.

“Harold Evans was a path-breaking journalist, who added a new dimension to investigative journalism. His demise leaves a huge void in the world of journalism”, IPI Executive Director Barbara Trionfi said. “We feel so privileged to have counted such a distinguished editor among our members for the past six decades. Harold’s contribution to journalism and press freedom will remain unparalleled.”

A long-time member of IPI and a former member of its executive board, Evans always maintained an active interest in IPI’s activities. In the early 1960s, for example, he offered his services and time to conduct workshops for news editors and reporters in New Delhi and other Asian centres. He was instrumental in developing an IPI training manual for news editors, The Active Newsroom. Written by Evans, this enormously successful publication explains with lively, practical examples how to make newspapers more readable through better news editing, reporting and layout.

In 2000, Evans received the IPI Press Freedom Hero award.

Evans, who founded and edited The Sunday Times for 14 years, was known for pioneering a new era of investigative journalism that exposed the plight of Thalidomide victims. He became the editor of The Times in 1982 but resigned after a year resigned protesting against what he considered manipulation by the new owner Rupert Murdoch.

From 1967 to 1981, Evans redefined the standards of British investigative journalism by founding The Sunday Times’ famous Insight unit of investigative reporters and backing them through a long series of scoops. Under his editorship, the paper uncovered the Kim Philby spy scandal and published, at the risk of criminal prosecution under the Official Secrets Act, the diaries of former Labour Minister Richard Crossman, which revealed “how the British system of government really works, for good and for ill.”

He will be remembered for this famous exposé, about hundreds of Thalidomide children in Britain, most of whom had not received any compensation for the severe birth defects inflicted on them because their mothers had taken the drug during pregnancy. Risking his career and professional reputation, Evans took on the drug companies and fought them for years through the English courts. He won a famous victory at the European Court of Human Rights against the suppression of the Thalidomide articles by the House of Lords, and the victims’ families won redress after more than a decade.

“It was one of the most memorable days of my life when … I sat in Strasbourg on April 26, 1979, and listened to the conclusion of ‘L’affaire Sunday Times’,” Evans wrote. “Twenty judges of the European Court had deliberated. … Nine of them were against us, including the British judge, but eleven carried the court: ‘We find there has been a violation of Article 10 [of the European Convention of Human Rights].’ This meant the House of Lords injunction had infringed our rights to free speech and that the law of contempt would have to be liberalised in Britain in the spirit of the Convention.

After leaving The Times, Evans became a director of Goldcrest Films and Television until 1984, when he moved to the United States to teach a course on the press and the U.S. Constitution at Duke University, North Carolina. That same year, he was appointed editor-in-chief of the Atlantic Monthly Press and subsequently editorial director of U.S. News and World Report.

He was president and publisher of Random House from 1990 to 1997 and editorial director and vice chairman of U.S. News and World Report, the New York Daily News, and The Atlantic Monthly from 1997 to 2000, when he resigned to begin full-time work on two major writing projects following up on the success of his acclaimed bestseller, The American Century.

Evans was awarded a knighthood by the British Crown for services to journalism in 2004. Speaking after becoming a Knight Bachelor at Buckingham Palace, he said: “I want to divide it up into 140 bits – most of my success comes from colleagues, so I call them all knightlets.”

In 2009, Evans released his critically acclaimed autobiography, My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times.