Last Sunday, Turkish voters narrowly approved constitutional changes that observers fear will lead to authoritarian rule under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. While international election observers have criticised technical aspects of the vote, Erdoğan’s crackdown on the press – including the jailing of at least 150 journalists – and nurturing of a state propaganda machine had arguably tainted the campaign well in advance.

Turkey‘s most egregious press freedom violations have occurred following last July’s failed coup attempt, but from the onset of his presidency in 2014 Erdoğan aggressively turned to criminal law to punish scrutiny of his actions and intentions. In 2015, Erdoğan’s first full year in his present office, a staggering 1,953 cases of insulting the president were opened, according to International Press Institute (IPI) research. By contrast, the same figure for the entire period from 1986 to 2014 – a 29-year span that saw five different presidents – was 1,502. (Figures for 2016 are not yet available.)

These cases, filed under Art. 299 of the Turkish Criminal Code, have targeted not only journalists, but also writers, politicians, athletes, students, academics, schoolchildren and even beauty queens, generating an atmosphere of fear in which spouses turn on each other. Erdoğan even managed to convince the Turkish Constitutional Court of his “right” to be shielded from criticism. In December 2016, the Court – in a ruling that ignored the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights – upheld the constitutionality of Art. 299 by emphasising the state’s legitimate interest in “preventing and punishing any attack against the dignity of the State in the personality of the President who is the head of the State and represents the State”.

While the abuse of Turkey’s presidential insult provision has few contemporary parallels, criminal laws prohibiting insult to the head of state are themselves common in Europe, as an IPI study published last month by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) revealed.

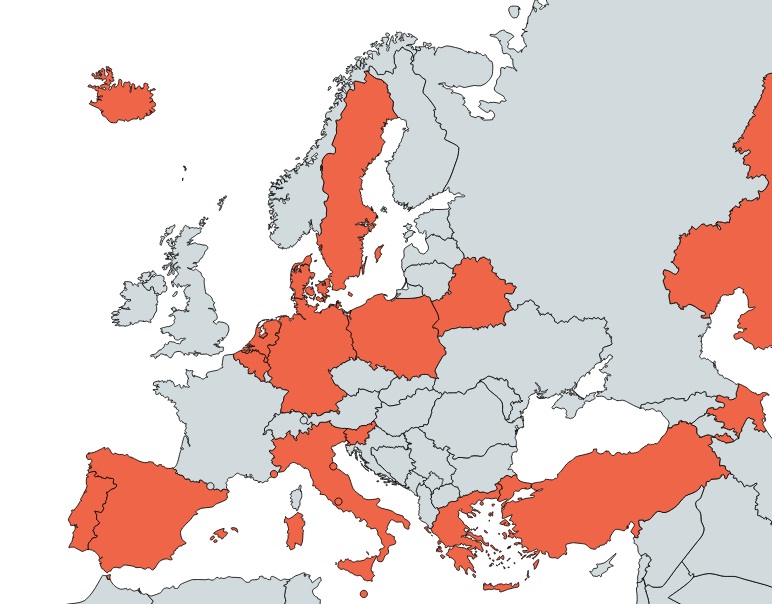

According to the study, 24 OSCE states offer special protection to the reputation and honour of their head of state: Andorra, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Malta, Monaco, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Vatican City. Imprisonment is a potential sanction in all cases. Most of these states are highlighted in orange below.

Of particular note are Europe’s lèse-majesté laws, which foresee some of the harshest criminal penalties for defamation and insult of any kind in the OSCE region. In Sweden, lèse-majesté carries a potential six-year prison term – three times the maximum possible sentence for defamation against private persons under the Swedish Criminal Code. In Denmark, persons convicted of insulting the monarch face four years behind bars; in the Netherlands, five. For comparison, Turkey’s Art. 299 provides sentences of up to four years.

In many of Europe’s republics, the long-standing principle that government officials must tolerate greater scrutiny is ironically turned on its head when it comes to the highest official. The IPI study showed that criminal penalties for defaming or insulting heads of state are often higher than similar acts against private persons. Iceland, for instance, doubles penalties for slander if the act was committed against the president. In Poland, insult can land a person behind bars for up to a year – unless the alleged victim is the president, in which case the maximum sentences rises to three years.

With the exception of Kyrgyzstan, the Central Asian states offer their heads of state elaborate protection from criticism, with trends headed in the wrong direction. Last November, for instance, Tajikistan, which already possesses a special law punishing defamation of the president with up to five years in prison despite having no general criminal defamation laws, added a new provision to its Criminal Code on “Public insult of the Founder of Peace and National Unity – Leader of the Nation or slander against him”, also carrying a potential five-year sentence. In totalitarian Turkmenistan, a decree contemplating a life sentence for “attempts to sow doubts” about the president’s policies remains in effect.

While the IPI/OSCE study did not look systematically at the application of head-of-state insult laws, it is clear that Turkey, despite being the most prominent example, is not alone. Belarus’ provision is also applied with relative frequency, perhaps most notably against Gazeta Wyborcza correspondent Andrezej Poczobut in 2012. Prosecutions or attempted prosecution has also occurred in EU member states in recent years, including in Poland, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands.

[separator style_type=”none” top_margin=”15″ bottom_margin=”20″ sep_color=”#eae9e9″ border_size=”” icon=”” icon_circle=”no” icon_circle_color=”#ffffff” width=”” alignment=”center” class=”” id=””]

[content_boxes layout=”clean-horizontal” columns=”1″ icon_align=”left” title_size=”18″ backgroundcolor=”#d5cb0b” icon_circle=”” icon_circle_radius=”” iconcolor=”#d5cb0b” circlecolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”#d5cb0b” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” icon_size=”” link_type=”” link_area=”” animation_delay=”” animation_offset=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ margin_top=”0″ margin_bottom=”0″ class=”” id=””]

[content_box title=”Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region” icon=”” backgroundcolor=”#d5cb0b” iconcolor=”#000000″ circlecolor=”#d5cb0b” circlebordercolor=”” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” iconrotate=”” iconspin=”no” image=”” image_width=”35″ image_height=”35″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

This post is part of a series of articles analysing the findings from an in-depth report authored by IPI researchers and published by the OSCE Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media in March 2016. Read the full report here.

Previous features:

Study: Insulting foreign leaders a crime in 18 OSCE states

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]