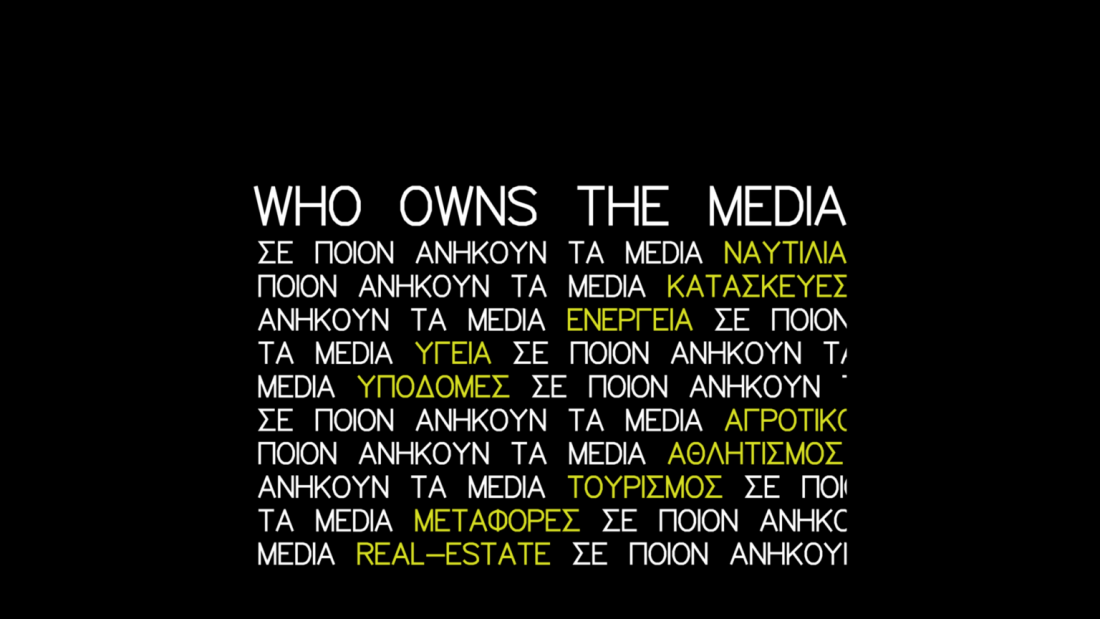

Greece-based media organization Solomon’s new investigation reveals the intricate ownership structures behind Greek media, linking 762 companies to 12 major owners, many involved in sectors like shipping, finance, and energy. With ties to tax havens, these owners wield media as a tool of influence. In this interview with the International Press Institute (IPI), Solomon’s journalist and data editor Corina Petridi discusses the findings, and the broader implications for press freedom in Greece.

—

At the beginning of 2024, a report authored by Solomon journalist Danai Maragoudaki and produced by IPI assessed systemic threats to independent journalism in Greece. Based on Somolon’s latest investigation, what were some of the new, most surprising revelations about the ownership structures of major Greek media groups?

Our investigation links 762 companies to 12 prominent media owners in Greece. 94 out of these entities are media companies operating mostly in Greece, controlling TV channels, radio stations, newspapers and online media among other things.

Apart from that, our research showed that their business activity expands in several business sectors. More specifically, we grouped their companies into 14 business sectors – the most frequent ones being maritime (164), finance (153) and energy (114).

An interesting pattern we stumbled upon was the shipping-sports team-media triptych; 6 out of the 10 groups we examined fall into this pattern, something that appears to be happening in other countries as well, according to previous reporting by the Wall Street Journal.

The companies we included in the network are registered in 32 countries. Half of them (386) are registered in Greece and then there’s Cyprus (122) and the Marshall Islands (61) – two countries identified as tax havens by the Greek Independent Authority for Public Revenue (IAEA). Cyprus appears to be an appealing jurisdiction for many Greek businessmen because of law taxation and also because the legal system allows service providers such as accounting and law firms to appoint nominee directors and shareholders in their clients’ companies, ensuring a significant degree of anonymity. On the other hand, the Marshall Islands appear to be welcoming for many shipowners, including four of the businessmen we investigated.

Finally, our reporting showed that the 10 biggest TV channels in Greece currently owe a cumulative total of 350 million euros in the banking system, which reveals that the Greek media industry is not a lucrative one, but rather one that is used to exert influence.

Solomon’s new report explores media ownership across 30 countries, uncovering business ties to sectors like shipping, sports, and real estate. Can you explain how the international business interests of Greek media owners impact domestic media narratives?

In this project, our goal was not to offer interpretations but to document in a systematic way the business activity of twelve top media owners in Greece. Before our investigation, one could find articles linking one company to an entrepreneur, but this information was scattered. Through our research, we confirmed what we were reading in these articles by attaining in most cases the official proof of ownership or by finding strong indications of ownership. We were also able to find dozens more companies whose ownership was previously unknown. We put all this information in one place, on the website we created, so that we provide the reader the necessary context to understand or suspect why a news story is published on one website and another one is not.

In any case, it is clear to us that a media outlet controlled by a businessman will never publish a negative story about another company owned by the same person, let alone launch an investigation into whether that company is involved in illegal activities.

The investigation took over 18 months of research. What were the biggest challenges you and your team faced (for instance, in accessing financial statements and business registries)?

To begin with, we had to go through thousands of corporate documents and -mostly- financial statements to find any piece of information that would be useful. We were looking for shareholders, mother companies, sub-companies and related parties in order to create the network of legal entities and individuals. We were also looking for other types of official documents, such as statutes and court documents.

That was a time consuming process, since in many cases we came across several shell companies. That means that we would frequently find that company X is controlled by company Y, and that the latter is controlled by company Z. In this way, we would have to go through the financial statements of several companies to get to the Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO).

And even so, finding the UBO was not always feasible, since many of the entities we stumbled upon were offshore companies which means that the shareholders’ information was not accessible.

How do you believe the findings of this investigation will contribute to the wider discourse on media capture and press freedom in Greece? What would you say are your most pressing concerns as journalists working in this country today?

As mentioned above, our goal was to provide pieces of information that up until recently were not provided in a systematic way neither by previous reports nor by the official authorities. It’s crucial for the citizens to know where they get their information from and for the journalists to know who they work for. Apart from that, we wanted to create a tool that our colleagues and other researchers could use for further reporting and research respectively. So in that sense, we hope that our investigation will be a starting point for more (media) transparency in Greece.

Due to how the media landscape is shaped in Greece and also the very essence of the project, we knew from the beginning that mainstream media wouldn’t pick up our story. Howerer, thus far we understand that there is a genuine interest by civilians, journalists, researchers regarding media ownership in the country.

We are very keen to have more of these conversations and also speak more with our community of journalists about how similar projects can be carried out in the future since one of the pressing issues in Greece when it comes to journalism is the difficulty to access official data.

For example, when we first started this investigation, online media were not obliged to mention the name of the company that controls them, its registered office etc. That means that in some cases we had to spend a significant amount of time to find that media outlet X is controlled by company Y. It was not before the first months of 2024 -when our investigation was already nearing its completion- that online media outlets began to register en masse in “Registry of Electronic Media”.

Another thing we come across very frequently is the refusal of public authorities and corporations to reply when we share the findings of a story before publication. For this project, when the investigation and the fact checking process was over, we sent to each media group a spreadsheet with the companies that we believe that are controlled by their owner. We wanted to give them the right to reply, comment etc. We called them to make sure they got our email and they reassured us that they did and they will get back to us. Two out of ten groups eventually replied. One of them indeed commented on the findings and the other one sent us repeated letters preventing us from publishing, a tactic that we see a lot lately.