Normally, the thought of facing nearly €2 million in libel claims brought by two very powerful business figures would be enough to make anyone nervous.

Greek journalist Augustine Zenakos, however, doesn’t seem nervous at all. He calmly sips his coffee and smokes his electronic pipe, his mind seemingly distracted only by his next article in the monthly investigative magazine UNFOLLOW, where he serves as editor-in-chief.

“Well, yes, if you think about it, €1.8 million is a huge amount and is really something that should make me worry,” he said with a smile in a recent interview with the International Press Institute (IPI). “But, these are libel suits that never actually reach court. We call them ‘frozen cases’ and they’re quite a common tactic in the Greek media landscape.”

UNFOLLOW is currently facing two such frozen cases. George Melissanidis, the son of Greek oil baron Dimitris Melissanidis, filed the first in 2013. The magazine had reported that George Melissanidis was a shareholder at Aegean Power (later renamed Hellas Power), a private electricity supplier that owed tens of millions of euros to the state electricity company. Melissanidis denied the report and sued for defamation, demanding €1 million in compensation.

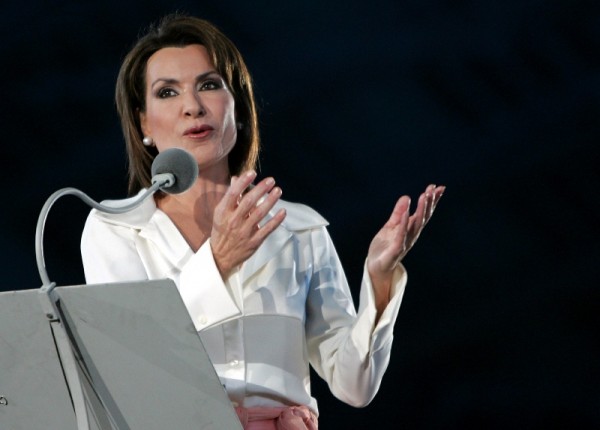

Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, a businesswoman and former president of the organising committee for the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, brought the second case last year. Τhe article that provoked her reaction examined her future business plans and her relationship with Greece’s Syriza party.

Angelopoulos-Daskalaki filed criminal charges against UNFOLLOW, requesting five months’ imprisonment for the authors of the article. In addition, she demanded €800,000 in compensation, in addition to €80,000 each time UNFOLLOW mentioned her name in an insulting way in the future.

Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki gives a speech during the closing ceremony of the Athens 2004 Olympic Summer Games. REUTERS/Adrees Latif

The pattern

According to Zenakos, in a frozen case the plaintiff’s lawyer calls the defendant and suggests that the case not go to trial. If the defendant agrees, then no one appears in court and the case is postponed indefinitely. The legal claim is suspended, although the plaintiff has the right to activate it again within the next five years.

Other Greek journalists say this pattern is not uncommon. Kostas Vaxevanis, editor of investigative magazine Hot Doc, told IPI he currently has 15 frozen cases pending against him.

“This is a regular tactic,” Vaxevanis said. “The plaintiff, instead of trying to prove that the article is not true, goes ahead and files criminal charges against the journalist, crying out to the public that he has sued the person who insulted him.”

In the case of UNFOLLOW, Zenakos said the delay brought by frozen cases can be “a good thing”.

He explained: “These [businessmen and politicians] are extremely rich. They can file charges every 10 minutes if they want and not have to worry at all about the costs. But for us things don’t go this way. We are just a small independent magazine. We do not have the money or the time to spend in courtrooms.”

Zenakos described a previous defamation suit in which four journalists from his team worked night and day to prove the magazine’s arguments to the court.

“We managed it, but the cost was huge,” he recounted.

For Zenakos, “freezing” a case can relieve journalists of this type of burden.

“If we can avoid all this trouble, even though we really believe that we are innocent, then we will,” he said.

UNFOLLOW Editor-in-Chief Augustine Zenakos. Photo courtesy Augustine Zenakos.

The catch

At first glance, it can seem that frozen cases are a win-win situation: no one loses money and no one is found guilty in court.

However, there is a catch: the ever-present threat that the case can be reactivated.

Vaxevanis described frozen cases as “a way of holding the journalist hostage and imposing a kind of self-censorship”.

He noted: “I know that if all these cases reach the court, I will be economically destroyed, even if I am found not guilty.”

Zenakos offered a similar explanation.

“The aim of this tactic is to scare the journalists so that the next time that they will want to write something concerning the plaintiff, they will think twice,” he said. “The frozen case is like a constant threat that keeps you hostage.”

But UNFOLLOW, for one, seems unfazed by the threat of frozen suits. The magazine continues to write and reveal scandals not only about the people who have sued them, but also numerous other politicians and businessmen.

“We are a kind of sui generis media,” Zenakos commented. “We are not scared or influenced by these things.”

Pausing before he rushes back to UNFOLLOW, and ready to make another politician or businessperson lose sleep, he adds: “We knew from the beginning that our journalistic work would cause [these type of] reactions, but we have decided that this a risk worth taking and that this is what we want to do in our lives.”