The Turkish government’s crackdown on independent media poses serious risks to democracy and stability, journalists from the country told a Vienna audience today at an International Press Institute (IPI) event examining media freedom in Turkey ahead of an April constitutional referendum that could vest even greater power in the hands of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

At a panel discussion and solidarity event titled “Turkey’s Media Under Siege”, celebrated media lawyer Fikret Ilkiz and acclaimed journalists Zeynep Erdim, Fehim Işik and Mehveş Evin discussed current threats and challenges to journalism and freedom of expression in Turkey, as well as the potential impact of international solidarity and pressure by NGOs, governments and the EU.

IPI Executive Director Barbara Trionfi, who opened the event, cautioned that if the present repression of critical journalists – ranging from online harassment, to physical attacks and criminal prosecution – continues, only those who refuse to criticise the government will remain.

Turkey is currently holding some 153 journalists and media workers behind bars, many of whom, their supporters argue, have been targeted for their journalism.

Participants at today’s discussion focused on the recent detention of Deniz Yücel, a correspondent for Germany’s Die Welt, as a troubling new low. Yücel, a dual German and Turkish national, was detained in Turkey last week after he was questioned about his reporting on the controversial hacking of emails of Energy Minister Berat Albayrak, Erdoğan’s son-in-law. On Monday, Yücel’s detention was extended under the current state of emergency, which Turkey declared following last year’s July 15 coup attempt.

Austrian author and journalist Petra Ramsauer, who moderated today’s discussion at Vienna’s Presseclub Concordia, said the crackdown on journalists should be viewed as a warning, as journalists are usually the first to be attacked when democracies come under threat.

Turkey’s crackdown on journalists continues as the country is set to hold an April referendum on constitutional changes that would turn the country into a presidential republic and extend Erdoğan’s power – a move that critics say would have a severe impact on the country’s few remaining checks and balances.

The panellists at today’s event noted that the deterioration of press freedom and free expression in Turkey has been a continuing process in recent years, as IPI and others have documented.

Ilkiz, former editor-in-chief of daily newspaper Cumhuriyet, pointed toward a 2011 report from then-Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Thomas Hammarberg indicating that the problem was linked to the malfunctioning of the judiciary.

“In the current situation, the judicial body is not protecting but suppressing freedom of expression”, Ilkiz argued. He accused the judiciary of having become “an arm of the executive body”.

He also cited IPI’s 2015 special report “Democracy at Risk“, which concluded that Turkish authorities’ failure to safeguard – and, in some cases, their steps to undermine – the right to share and receive information had led to serious deficiencies in the country’s democracy.

Ilkiz rejected Turkish government claims that those imprisoned, most on terrorism-related charges, were not charged due to their profession but because they had engaged in criminal acts.

Participants noted that the criminal charges against government critics discouraged journalists from covering certain topics and pushed them into censoring themselves. They also pointed to the way in which abuse of economic conditions and threats against journalists complimented other efforts to strangle independent thought.

Erdim, who has covered Turkey and regional developments for BBC World Turkey since 2004, said Yücel’s arrest showed that the government was also willing to extend pressure against foreign media. She explained that it has been getting harder for foreign journalists to get press cards and accreditation, and that high officials frequently refer to foreign journalists as spies, making their position within the public sphere even more fragile.

Işik, a journalist for pro-Kurdish Evrensel and editor-in-chief of Germany-based Artı Gerçek, emphasised the even-more-precarious situation that journalists for pro-Kurdish media outlets faced. The journalist was previously imprisoned for two years and fled to Germany last year when he again came under similar threat. He recounted not only the hardships that journalists targeted by the government face – he said he had lost seven colleagues over the course of his career – but the impact that has on their families.

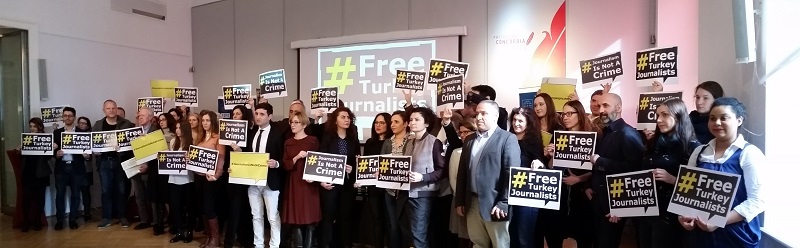

At the close of the discussion, journalists, NGO representatives and members of civil society held a display of solidarity for their imprisoned colleagues, posing for a group photo with signs calling on Turkey to “Free Turkey Journalists” and stating that “Journalism Is Not a Crime”.