On September 4, 2017, independent English-language newspaper The Cambodia Daily, which had reported in the country for 25 years, went to print for the last time.

After being forced to close over a tax dispute widely seen as a politically motivated attempt to harass the newspaper, its last edition led with a front-page story about the arrest of Cambodia’s main opposition leader.

The newspaper’s closure, and its final story, were emblematic of a far-reaching crackdown against checks on power by the regime of Prime Minister Hun Sen in the run up to the 2018 election.

In the months after the closure, authorities waged a massive campaign against the free press, shutting 32 radio stations, intimidating journalists and banning foreign-funded broadcasters.

The final blow came in May 2018 when the last major independent media outlet in the country, the Phnom Penh Post, was sold to an investor with links to the regime, leading to the resignation of many of its senior reporters.

In less than a year, the country was purged of independent media, leaving the public at the mercy of pro-government messaging.

Independent media returns

Two years later, however, there are finally signs that the fightback for independent media and press freedom in Cambodia may have begun.

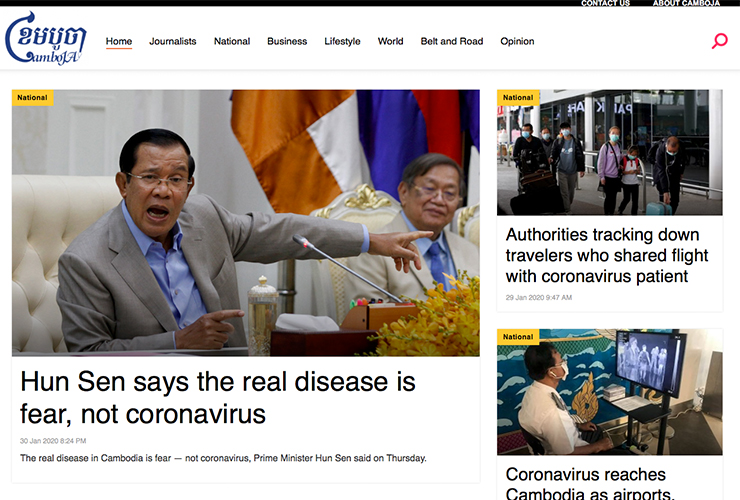

At the end of 2019, several former Cambodia Daily and Phenom Penh Post reporters officially joined forces to establish the Cambodian Journalists Alliance (CamboJA).

This body is made up primarily of “journalists who faced government repression in the run up to the 2018 election”, May Titthara, CamboJA’s executive director and a former national news editor at the Phenom Penh Post, told the International Press Institute (IPI) in a recent interview.

They are joined in a network of over 100 professional reporters and freelancers who will work from their base in Phnom Penh to defend journalists, professionalize the industry and promote media freedom.

On top of this, the association also aims to provide citizens, and the wider world, with a source of credible and independent English-language news from within Cambodia, Titthara added.

Having successfully registered with the government’s Information Ministry – as required by law in Cambodia – operations formally began on December 13.

A fresh perspective

A key motivation to set up the alliance was the fact that Cambodia has experienced “no significant improvements seen in the independent media environment in the years following the media crackdown”, Titthara said.

Worse still, many Cambodian journalists who do speak out or publish critical reports face retaliation from the authorities, he added.

“Many journalists are afraid to cover to sensitive stories because they worried about their security”, he explained. “Independent journalists face many challenges as they fulfil their duties; discrimination, intimidation, accusations, harassment and attacks have been committed against journalists and remain commonplace.”

To tackle these challenges, the organization plans to coordinate advocacy work to defend persecuted journalists. Another part of the thinking here is simply to give the country’s independent journalists somewhere to call home, Titthara explained.

“Independent journalists – whether working for the rare remaining independent outlet or as freelancers and citizen journalists – have had few avenues of support and coordination, or opportunities for earning a livelihood”, he said.

CamboJA’s website now provides them an online space where this kind of reporting can be published. Already, this has begun to fill some of the void left by the closure of The Cambodia Daily.

A glance at the website shows in-depth reporting and investigations about press freedom, corruption, diplomacy and politics – all topics that until recently might have lacked unbiased reporting in Cambodia.

Challenges remain

Nonetheless, Titthara thinks there is still a lot of damage to undo. “The closure of independent media outlets has had a huge negative impact on democracy and people’s rights, particularly the right to access to information”, he said. “Cambodian people living in rural areas have been cut off from unbiased information about their society.”

Another challenge is the possible retaliation they might face. After the crackdown, some journalists were arrested, while others fled into exile for fear of persecution. Recently the Cambodian government also handed authorities new powers to investigate and sanction those found guilty of publishing stories it deems as “fake news”. These powers include revoking media licenses, shutting websites and substantial fines.

In this legal minefield, the risks for those publishing independent media are high. “We understand about the risk but if we did not do it, who will?” Titthara concluded. “We try to keep the risk at the back of our minds and look straight forward for press freedom.”