[content_boxes layout=”clean-horizontal” columns=”1″ icon_align=”left” title_size=”” backgroundcolor=”#e6eef0″ icon_circle=”” icon_circle_radius=”” iconcolor=”#e6eef0″ circlecolor=”#e6eef0″ circlebordercolor=”#e6eef0″ circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”#e6eef0″ outercirclebordercolorsize=”” icon_size=”” link_type=”” link_area=”” animation_delay=”” animation_offset=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ margin_top=”0″ margin_bottom=”0″ class=”” id=””]

[content_box title=”” icon=”” backgroundcolor=”#e6eef0″ iconcolor=”#000000″ circlecolor=”#e6eef0″ circlebordercolor=”” circlebordercolorsize=”” outercirclebordercolor=”” outercirclebordercolorsize=”” iconrotate=”” iconspin=”no” image=”” image_width=”35″ image_height=”35″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

The following is the second in a series by IPI examining developments affecting press freedom in Myanmar in the wake of IPI’s 2015 World Congress in Yangon. Read the first story here.

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]

Proceedings moved forward in Myanmar this week in an inquest into the October 2014 death of journalist Aung Kyaw Naing, better known as Ko Par Gyi, who was killed while in military custody – an inquest that began last month without his wife’s knowledge.

Moreover, it is unclear who might be charged should the proceeding result in a finding that Ko Par Gyi was murdered, given that a military court ordered two soldiers accused of shooting him acquitted of charges of death by negligence six months ago in a decision only brought to light earlier this month.

Four witnesses testified in the Kyaikmayaw Township Court on Monday in the inquest into Ko Par Gyi’s death. Naw Say Phaw Waa, a reporter who covers the trial for the Myanmar Times, told IPI that the witnesses were “local residents” who “talk[ed] about what they have seen before Ko Par Gyi went dead”.

Naw Say Phaw Waa said that during Monday’s testimony: “One of the witnesses said he saw Ko Par Gyi with wet clothes. Then he informed the police. A few days later, he read in the newspaper that Ko Par Gyi was dead.”

The inquest at the civil court started silently in April and followed an even-more-significant decision made in a similar fashion last year by a military court – in both cases, without the knowledge of Ko Par Gyi’s wife or the media.

On May 8, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission released a statement saying that the Ministry of Defence had informed them that “an order of acquittal was passed on two guard soldiers” from a Military Court regarding the death of Ko Par Gyi.

However, Dutch journalist Yola Verbruggen told IPI that the military court actually made the decision to acquit the two soldiers – Lance Corporal Kyaw Kyaw Aung and Private Naing Lin Tun – on Nov. 27.

“The military did not make it public; they are rather good at keeping things to themselves”, she said.

In an article published earlier this month, Verbruggen and fellow journalists Naw Say Phaw Waa and Lun Min Mang quoted the vice chair of the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission, U Sit Myaing, as saying that the institution “received this information in April” in response to a request that it made concerning the case.

The revelation means that the Human Rights Commission was unaware of the acquittal when it issued a report on the death of Ko Par Gyi on Dec. 2, a report requested by Myanmar President U Thein Sein.

According to the report, the members of the commission visited Maw La Myaing, Kyaikmayaw and Mawlamyine during November 2014 and met with, among others, police and army officers.

On Sept. 30, Ko Par Gyi was reportedly returning from covering violent clashes between the military and a rebel group, the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), near the border with Thailand when he stopped to drink fruit juice and water in a shop near the river bank in Kyaikmayaw. According to the Myanmar Times, he then asked a motorbike driver to take him to the bus station.

The newspaper, summarising one witness’ account, reported: “When the driver passed a monastery, they were stopped and Ko Par Gyi was suddenly arrested. A few minutes later, the driver said, a military truck came to take Ko Par Gyi away. He was taken to the headquarters of Tatmadaw battalion 208.”

According to the December 2014 Human Rights Commission report, on Oct. 4 while in military captivity, “Ko Par Gyi said he wanted to urinate, so the guard untied his ropes”.

The report continued: “His right hand though was still tied. After he had urinated, the guard again bound his hands. At this moment, [Ko Par Gyi] shoved the guard down with his body and when the guard fell down, [Ko Par Gyi] tried to wrestle the gun from him. It was then that the second sentry, a Lance Corporal fired (2) short bursts with his rifle. In the ensuing struggle, a shot also went off from the first sentry’s gun. [Ko Par Gyi] fell down on the spot. Upon hearing the gunshots, the platoon commander and other officers arrived on the spot. The medic examined the body and found that Ko Aung Naing has died of (5) gunshot wounds. The time was 7:45 pm in the evening.”

When Ko Par Gyi’s body was exhumed in early November, it was revealed that he had suffered a cracked skull, broken ribs and a broken arm. The Human Rights Commission recommended that the matter be brought before a civilian court.

Given the news about the military court’s acquittal, IPI asked the Human Rights Commission whether it planned to take additional actions in the case.

“The Commission has issued two statements on that matter and all our findings have been reflected in those statements,” Commissioner Nyunt Swe responded. “Therefore, we have nothing more to comment.”

Two months ago, during IPI’s 2015 World Congress in Yangon, Myanmar Information Minister U Ye Htut promised “irreversible reform” on media freedom. But, like the Human Rights Commission, government representatives were silent regarding the acquittal when contacted by IPI this month.

Twelve journalists are currently in prison in Myanmar in relation to their reports on the military or government officials, or their coverage of protests. Three of them are serving a seven-year sentence.

Human rights activist and former political prisoner Zaw Thet Htwe told IPI that the Ko Par Gyi case was important for the transition to democracy.

“It showed that military power is stronger than civil administration and media,” he said.

Ma Thandar, Ko Par Gyi’s wife, told IPI that she will never accept the decision of the military court. She was at the Kyaikmayaw civil court to listen to the witnesses on Monday. She said she is “keen to understand from the witnesses about what they knew of the death” of her husband.

Thandar testified herself on May 11 at the same court about how she met Ko Par Gyi, as well as how she was informed of his death and her struggle to have his body exhumed.

But her testimony came more than one month after the inquest started silently on April 10.

“The first two hearings took place without Ma Thandar knowing about it and thus were not attended by her or the media”, Verbruggen told IPI.

Ma Thandar said she had not been sent any invitation to testify or any information that the inquest had started. A judge reportedly blamed the postal service for not delivering letters in two instances, but when Thandar asked for the copies of those letters she says she never received them. She learned that the inquest had begun from a local journalist. Then she went at the court on April 30, where the prosecutor gave her an invitation to testify.

Police reportedly asked the court for the inquest following the complaint of Ma Thandar.

Verbruggen said she has attended two court sessions so far.

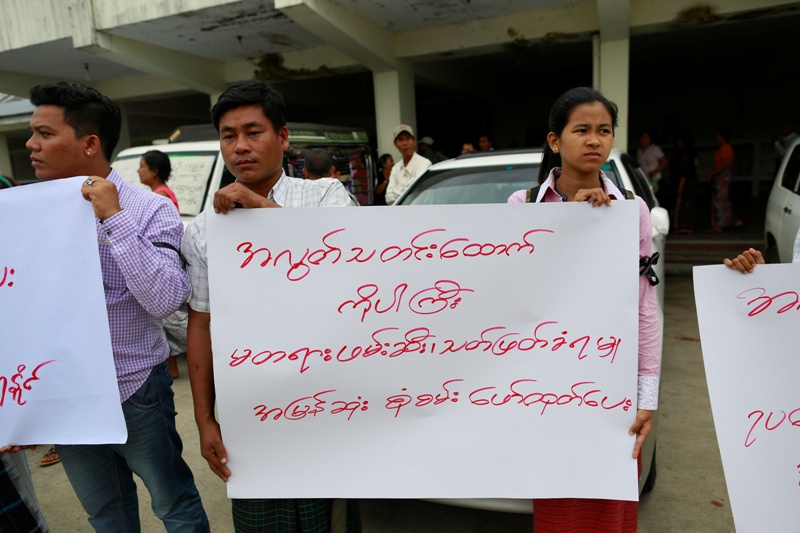

“I was at the trial on 30 April and 11 May”, she told IPI. “Media was allowed to attend the trial as was Ma Thandar. Supporters listened from an open window with permission of the court”.

Thandar is represented by a well-known local human rights lawyer, U Robert San Aung. He and his client want the military personnel tried in civil court. However, both the prosecutor and the judge in Kyaikmayaw maintain that the current civil trial is only about finding out how Ko Par Gyi died.

“No one is accused in this trial,” local journalist Nay Say Phaw Waa said. “The court said their duty is just to find why Ko Par Gyi was dead. But later, if Ma Thandar finds out a specific person, she can sue or accuse (him).”

According to Verbruggen, about 40 witnesses in total are anticipated to testify. Ten of them have already been heard. The court is expected to issue a report on the circumstances of the death.

It is unclear whether military personal will testify.

“The court said they would hear from the military after hearing all the witnesses from locals,” Verbruggen said. “As far as I know it [the military] has not yet said whether it will cooperate.”*

Nay Say Phaw Waa added: “The civil court can’t charge the military.”

IPI Director of Advocacy and Communications Steven M. Ellis said he feared that the nature of the proceedings examining the death so far foreshadowed a potential lack of accountability.

“According to IPI’s Death Watch, Ko Par Gyi is the first journalists in Myanmar to die in connection with his or her work since we began recording such deaths in 1997,” he said. “We are concerned that a failure to achieve justice in this case will set a negative precedent with respect to impunity for violence against journalists and will represent another obstacle to Myanmar’s ongoing democratic transition.”

Thandar’s lawyer, U Robert San Aung, did not strike a hopeful tone in comments to Verbruggen and her colleagues when asked about the proceedings on May 11.

“They are just tricking us,” he said.

*Correction: this quote was corrected on May 28. It originally incorrectly attributed a statement by Nay Say Phaw Waa to Verbruggen.