Lesen Sie diesen Artikel auf Deutsch

As Austria heads into the final days before a Dec. 4 presidential election, one contender’s backers increasingly face accusations of encouraging the online abuse of journalists.

The allegation comes amid an election that has hardly been routine: candidates from Austria’s two traditionally strongest parties failed to make it past the first round in April, leaving one nominally independent candidate to face off against a candidatefrom the right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ).

The independent, Alexander Van der Bellen, a former Green Party leader, narrowly defeated the FPÖ’s Norbert Hofer in May, but the result was annulled due to irregularities and an Oct. 2 repeat election was postponed over technical problems with ballot envelopes.

Now, as the decisive contest between the two finally looms, critics say the FPÖ has used its strong social media brand to promote abuse targeting journalists perceived to be its critics, in behaviour ranging from innocuous insults to implied, and sometimes outright, threats.

In order to examine those accusations, the International Press Institute (IPI) conducted a case study of major FPÖ social media accounts in early September and mid-October 2016. It found that even when FPÖ figures engaged in criticism of journalists that could be regarded as full within the bounds of free speech, albeit sometimes unfair or impolite, those statements often ignited a vitriolic reaction by party supporters against the journalists.

The FPÖ’s digital communication strategy is generally regarded as the best among Austrian political parties. In the last few years, the party has built strong brands on social networks to deliver its message to the public without filters. Four of the top 10 politicians with larger social media presence in Austria belong to the FPÖ, according to Politometer.at, which ranks the social media presence of the country’s politicians.

However, FPÖ politicians use social media platforms such as YouTube or Facebook not only to disseminate links, videos or live streams, but also to criticise political opponents and others who are not part of the immediate political arena, including journalists.

The party leaders sell themselves as the underdogs, and the FPÖ as a party seeking to fight the system. The relationship between the FPÖ and professional journalists is tense, but also ambivalent: FPÖ politicians take part in TV discussions hosted by national public service broadcaster ORF and private channels, and give interviews to most print and online media.

Afterward, they post the interviews on their social media accounts, primarily on their official Facebook channels. In some cases they post critical comments singling out the journalist who interviewed them, implicitly equating the journalists with the very same “system” the FPÖ says it is fighting and labelling mainstream media or critical news outlets “Systemmedien” (media that are part of the “system”).

By comparison, Austria’s two major parties – the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) and the centre-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) – also criticise the media publicly. But that criticism is usually less aggressive and less personalised, and observers say those parties’ supporters’ real efforts to influence the media take place over thetelephone.

The case study

IPI’s research focused on the Facebook page of FPÖ chairman Heinz-Christian Strache. This page plays a central role, as it is used to share important posts from other FPÖ pages, increasing their reach. As of the end of October 2016, Strache’s verified page had more than 430,000 fans, more than five times as many as the official FPÖ fanpage, with more than 78,000 fans.

Attempting to draw a line between legitimate criticism and abuse, the study closely examined 10 Facebook posts from “HC Strache”, as he is commonly known, that singled out journalists for criticism. The study did not examine abuse directed at social media activity not directly related to the journalists’ work.

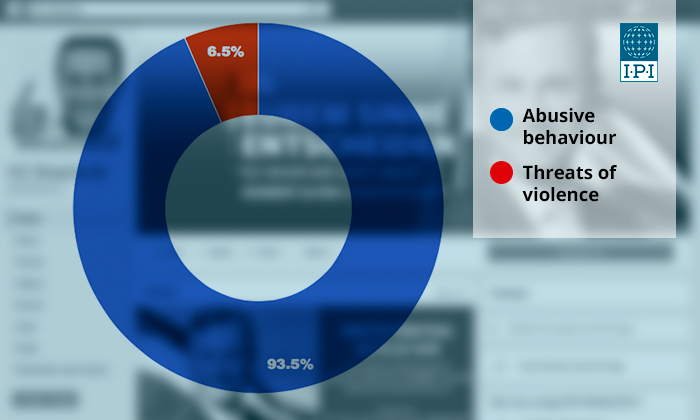

In total, the case study identified 92comments on the 10 posts on Strache’s Facebook page during the period in question that contained insults or threats to journalists. As noted, this figure could be higher, particularly as it is unclear whether any comments were deleted.

The study determined that six of the comments constituted “implicit or explicit threats of violence” that could result in a criminal investigation if a complaint were made to police. The other 86 comments were determined to constitute “abusive behaviour”, i.e., essentially offensive remarks directed against a person or their physical appearance.

IPI sought comment from the FPÖ about these comments, but the party declined to answer.

Graphic 1. Data: IPI Ontheline Database. Graphic created using Google Fusion Tables.

Comments below the posts on Strache’s page tended to focus on allegations of the media’s being biased, part of the “system” or openly hostile toward the FPÖ. This narrative was also found repeatedly in the posts themselves (“Armin Wolf, as a ‘journalist’, pursues policy against the FPÖ”).

The comments ranged from explicit and implied threats (“Ms. [Ingrid] Thurnher will one day be presented with the bill”, “remember that face, impress it in your memory”, “we know where they belong … ‘crimes against one’s own people’ should be rigorously punished in Europe”), to simple, if boorish, insults to mental capacity(“How can this dimwit demand an independent ORF?”, “He’s a case for the psychiatrist”, “She will soon need the attention of a medical specialist”) and appearance (“Has she ever taken a look in the mirror? She’s ugly as hell”).

As for the 10 posts – which were often also shared by other, far-reaching FPÖ-linked pages– they ranged from sharing an article of the FPÖ-linked page Unzensuriert (“[Florian] Klenk and Wolf: Leftist journalists drive constitutional court judge toward self-demolition”) to targeted criticism of a specific journalist (“…more than unworthy and completely unacceptable”). In some instances, the posts themselves were not overtly critical; a post containing an interview presented on a television program was enough to draw abusive comments against the journalists involved.

Screenshot of the ‘HC Strache’ Facebook page, with a post published on Nov. 16, 2016 featuring ORF anchor Armin Wolf interviewing Hofer.

Gender component

A clear gender component was also strikingly evident. While the majority of the 10 posts on Strache’s page singled out male journalists, the posts targeting female journalists drew a much greater number of negative comments: 75 of the 92 examined, including six comments deemed threats and 69 comments deemed abuse. Whereas comments targeting male journalists tended to criticise their work and question their independence, comments against female journalists were more likely to refer to appearance (“I don’t even look at the woman any more, I’m so nauseated”), or contain sexual-related insults (“I don’t like the bitch, she’s just disrespectful”) or threats of physical violence.

Graphic 2. Data: IPI Ontheline Database. Graphic created using Google Fusion Tables.

In one case, the FPÖ cut together old footage from ORF programs such as “Im Zentrum” or “Runder Tisch” to produce a misleading videoalleging to show journalist Ingrid Thurnher making unfavourable facial expressions in reaction to comments by FPÖ politicians, and shared it under the title “A look says more than a thousand words”. The video evoked a strong response from commenters on Strache’s Facebook page, exposing Thurnher to intensely negative reactions.

The impact on the journalists

Many of the journalists targeted said they do not follow Strache’s Facebook page carefully and only learn about his posts indirectly.

“I only become aware of them when numerous similar-sounding comments suddenly appear on my Facebook page, often under totally un-related posts of mine,”ORF prime time newsanchor Armin Wolftold IPI in an interview.

Wolf said that although he briefly looks to see what post Strache dedicated to him, he does not read the comments on Strache’s page, explaining: “I don’t expect to find much constructive criticism there.”

Florian Klenk, editor-in-chief of weekly news magazine Falter, confirmed that he took a somewhat similar approach.

“I notice that I’m being discussed somewhere on a right-wing page when the e-mails swell up,” he said. Klenk noted that while he sometimes looks for the source, sometimes he simply does not care.

“It’s basically childish,”he said. “Strache and [FPÖ member, Vienna vice-mayor Johann] Guldens are making noise in their own echo chamber. They’re yelling around in a digital cellar. Sometimes the door opens and something seeps out.”

Klenk added that he does not need to visit this cellar every week.

At least in this study, the phase of intense hatred following Strache’s posts usually lasted only briefly. Nevertheless, the journalists targeted described the phenomenon as being extraordinarily invasive and said that it ranged from “annoying” and “burdensome”, to “frightening”. In one case, a journalist who declined to be named in this article was offered, but declined to accept, police protection.

But even in cases that appear milder, the proliferation of such comments carries the possibility that journalists will withdraw from certain platforms and no longer reach certain audiences, if not from fear of actual violence, then because dealing with them is so time-consuming and nerve-wracking.

“Because of such experiences, I am rarely or hardly ever active in the social networks,” Christa Zöchling, a journalist for Profil, observed.