The IPI global network demands the immediate release of Antonina Favorskaya, an independent Russian journalist who is being investigated for “participating in an extremist group” following her reporting on Alexey Navalny. Favorskaya was arrested on March 29, and, if convicted, faces up to six years in prison.

The arrest of Favorskaya appears to be a clear attempt to end all reporting on the deceased opposition leader Alexey Navalny, his surviving collaborators – nearly all of whom are now in exile – as well as the work of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund (FBK). The arrest represents a new phase in repression of Russia’s media from a government that tolerates no dissent.

The case against Antonina Favorskaya

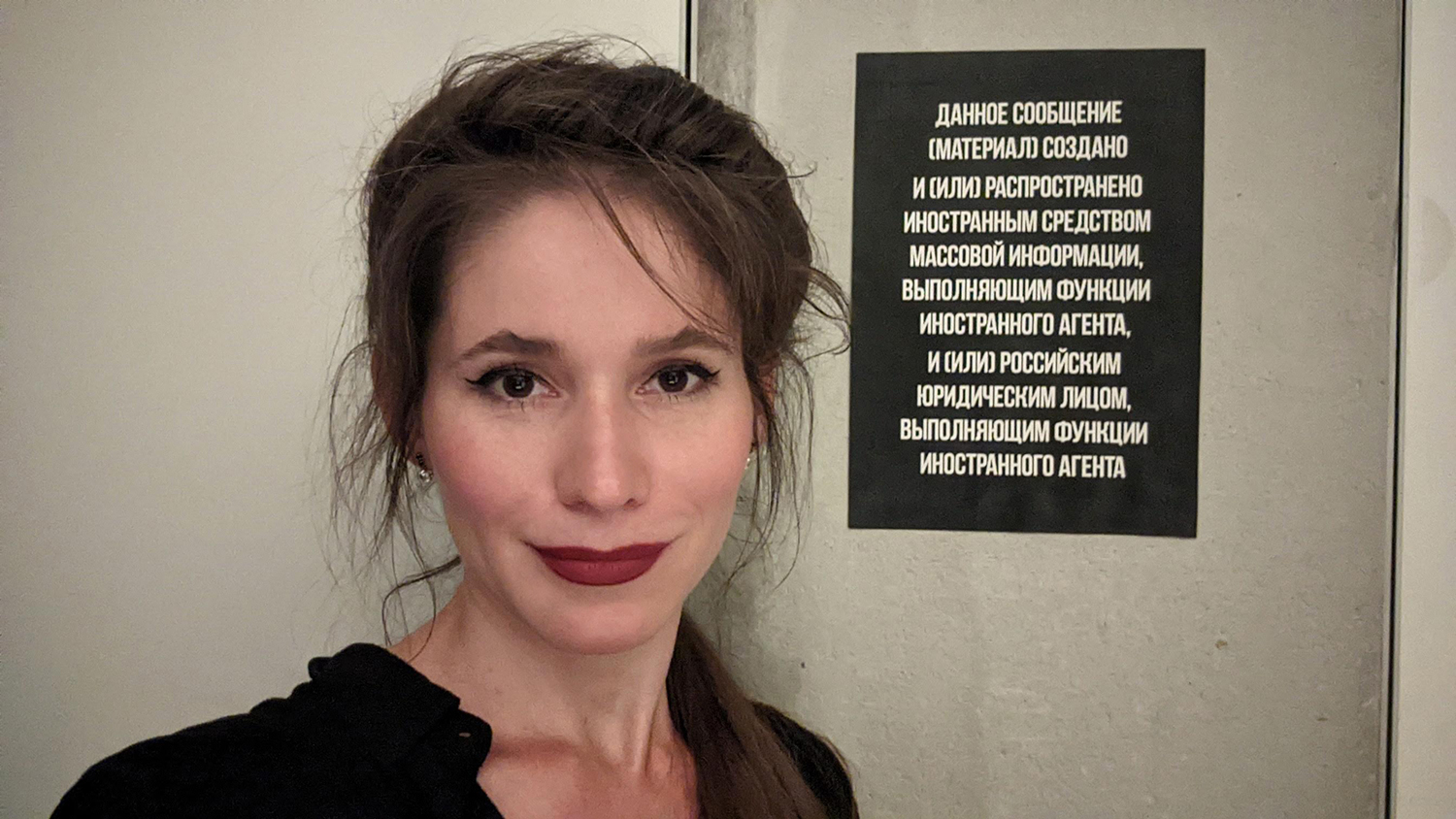

A journalist for the independent news outlet SOTAVision, Favorskaya is the author of multiple reports on the trials of Alexey Navalny. She is known for having recorded what is thought to be the last video of the Russian opposition leader before his death, at a court hearing in his case on February 15.

She was first detained on March 17, after she visited Navalny’s grave with two of her colleagues.

Following their visit, the three journalists were approached by the police while they sat at a nearby café on the outskirts of Moscow, and were asked to present their documents. Anastasia Musatova and Favorskaya were both subsequently detained and taken to a police station. While Musatova was released hours later, Favorskaya was held overnight and then handed a 10-day prison sentence on charges of “disobeying police”.

Security officials claimed that the journalist would have initially refused to show her documents. However, Favorskaya said the charges, which were identical to accusations previously formulated against Kremlin opponents, were completely fabricated.

Favorskaya’s 10-day sentence ended on March 28. However, she was immediately re-arrested in front of the jail to face a new criminal case for “participation in an extremist group”. The authorities claim that Favorskaya authored unspecified publications for Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund (FBK). This was denied by Kira Yarmysh, the press secretary of the deceased politician.

On the same day, the police again detained Musatova, as well as photographer Alexandra Astakhova, who were waiting for Favorskaya outside the prison. Security forces then searched their homes, as well as that of Favorskaya. Musatova and Astakhova were released soon after, after being handed witness status in the case against Favorskaya.

Police also detained SOTAVision correspondent Ekaterina Anikiyevich and RusNews reporter Konstantin Zharov, who were reporting next to Favorskaya’s home as police searched the premises. Zharov was reportedly beaten during his detention. Both he and Anikiyevich were released on the same day.

New crackdown on media after Navalny’s death?

While a handful of local Russian journalists are already in prison for disseminating verified facts on Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine – which the Russian authorities consider “fake news” – the arrest of Favorskaya has introduced considerably more legal uncertainty for those Russian journalists who chose to stay inside the country and not cover the war in Ukraine.

The case against Favorskaya seems to indicate that authorities are now ready to weaponize legislation on “extremism” and jail journalists on a larger scale, as has been the case in neighboring Belarus since the crackdown on mass protest movements in 2020.

In fact, while FBK was designated as “extremist” in 2021, up until now, no journalists had been targeted for independent reporting on activities by the Fund and its now-deceased leader. This was the case even though the legal instruments to repress media for such reporting had already been established.

Favorskaya’s arrest, which shows how these instruments can be applied at will, exacerbates the already uncertain situation for Russian journalists still based in the country.

As of April 2024, no fewer than 17 Russian journalists are behind bars on various accusations, according to IPI monitoring. Five are serving sentences, or are behind bars while under investigation, on charges of “discrediting the Russian army” or publishing verified news on the war in Ukraine which Russian authorities consider to be “false information”.