Spanish journalist Mayte Carrasco spent years covering deadly conflicts across the globe, from Afghanistan to Libya. But it was from the safety of her own home that she faced some of the most vivid threats to her life.

Not long after Carrasco published a book based on her coverage of the war in Syria in May 2014, she began to receive dozens of abusive and threatening messages on Twitter.

“In the twilight of your days you will hear from us,” one tweet from an anonymous account read.

Carrasco is far from alone. Online harassment of journalists is widely reported to be on the rise, including in countries with a traditionally strong record on press freedom. Coverage of this phenomenon, however, has largely been restricted to anecdotal evidence.

International watchdogs such as the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and academic researchers around the world have highlighted the need for systematic monitoring and analysis to better understand the scope of online abuse targeting journalists.

With these calls in mind, the International Press Institute (IPI) today launched an online database aimed at recording harassment, abuse, threats, hacking and other web-based methods of intimidating independent media into silence.

Intended as a resource for journalists, researchers and media freedom advocates, the database currently contains 766 verified instances of online abuse against journalists collected in two pilot countries, Turkey and Austria. It will be updated on a regular basis to reflect ongoing data collection and will be expanded to cover additional countries.

The database forms part of IPI’s Ontheline programme, initiated in 2015 in order to combat growing online attacks on the media. During the programme’s initial phase, IPI researchers conducted more than 50 in-depth interviews with journalists targeted by online mobs as well as with experts in cyber security, social network analysis, psychology and other fields. In January 2016, IPI began systematically monitoring social media platforms in Turkey to record instances of attacks on journalists.

The data collection follows a standard methodology to better study this emerging threat to independent journalism.

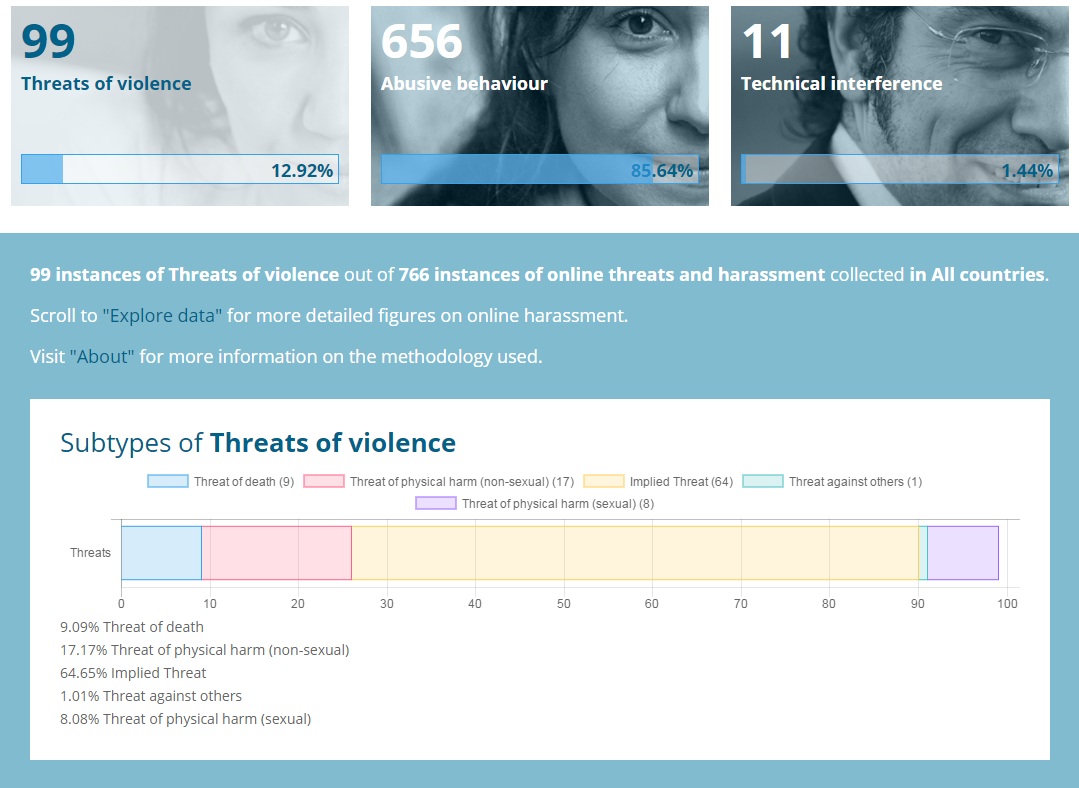

First, instances of online abuse are classified according to three broad categories: violent threats, abusive behaviour and technical interference. In a second step, each attack is analysed using nearly 20 variables, ranging from the type of victim (journalist, news website, media corporation) to the background issue that appears to have prompted the attack (religion, nationalism, politics, education, etc.).

This present feature looks specifically at the 674 instances of online threats and abuse against journalists collected in Turkey. IPI released an analysis of preliminary data from Austria on Dec. 2, two days ahead of that country’s presidential election.

Over the last four years, Turkey has witnessed a rise in organised social media campaigns – primarily on Twitter, the main driver of online political debate in the country – intended to silence critical reporting. These campaigns frequently consist of vicious smear propaganda or threats of violence, as seen in the following tweet directed at IPI Executive Board Member and Cumhuriyet columnist Kadri Gürsel, who was jailed in October on flimsy charges under emergency powers granted to the government as part of Turkey’s post-coup crackdown:

@KadriGursel önce sizin gibi terörist ajanların fişini çekmeli devlet düşmanları.

@KadriGursel first they should unplug terrorist spies like you, enemies of state.

Graphic 1. Data: IPI Ontheline Database. Graphic created using Google Fusion Tables.

Due to the sheer scale of the research subject – the online campaigns can include thousands of postings, while smaller, less-organised attacks may frequently escape detection – the data collected under this programme is not intended to be exhaustive. The aim, rather, is to provide a snapshot of an ever-more-intense phenomenon so as to identify overall trends and aid in the development of countermeasures.

Threats of violence

Initial data collection in Turkey between January and November 2016 recorded 93 instances of threats of violence against journalists. This figure amounts to almost 14 percent of all instances of online abuse in the country during this period. Of these 93 instances, over two-thirds can be sub-classified as implied threats, i.e., threats to harm the target that are not explicit but can be understood by “reading between the lines”.

Graphic 2. Data: IPI Ontheline Database. Graphic created using Google Fusion Tables.

Another prominent sub-category is comprised of threats of physical harm and similar threats that involve a sexual component. Of particular concern are threats of rape or other sexual abuse directed at women journalists; these tend to be particularly vicious and vivid.

@candundaradasi @t24comtr Türkiyedeki okur sana ulaşmak istiyor mu acaba? Bunu hiç düşündün mü ? Milletin eline düşsen linç edecekler.

I doubt whether Turkish readers want to reach you. Have you ever thought about it? If you fall into the hands of these people, they will lynch you.@banuguven @candanyildiz @imc_televizyonu @nezahat_dogan yakında ailen bildiğin herkesi sikecem 360 derece sağ sol hepsi

I will soon fuck your family, anyone who you know well, 360 degrees, from right and left, everywhere.

This tweet was addressed to Banu Güven, a female journalist working for the television channel IMC TV.

We have recorded ‘just’ eight death threats in Turkey thus far. However, it must be noted that such threats, by their very nature, are among the forms of abuse most likely to silence their intended targets. The data point, therefore, belies the impact this category can have.

@melisalphan @tuncayopcin Yalancının şerefini sikeyim mi? İspatlayın amına koyduğumun domuzları yoksa ölümle gelirim size şerefsiz evlatları.

Honourless liar! Prove it, you fucked pigs, otherwise I will come to you with death, sons of dishonoured!

Abusive behaviour

The pilot phase in Turkey revealed abusive behaviour to be the most common type of online attack. This category can be further divided into eight subcategories: verbal smear, verbal insults, fake content, impersonations, false light, fake content, cyber surveillance and doxxing. The study recorded instances of abusive behaviour in six out of the eight subcategories.

Graphic 3. Data: IPI Ontheline Database. Graphic created using Google Fusion Tables.

Of the 570 instances of abusive behaviour in Turkey, more than half (292) can be classified as verbal smears. These instances are normally part of social media campaigns that seek to discredit journalists and their work.

@candundaradasi siktir amk halk seni hain bir piç olarak görüyor amk yavşak vatansızı

Fuck off! The Turkish people see you as a traitor bastard. You fucked up stateless asshole!Bu Kadri Gürsel gibi gazeteci kılığındaki hainleri halkın gözüne sokmak lazım.

The traitors, who disguise themselves as journalists like Kadri Gürsel, should be exposed to the public.

Trolls in Turkey also resort to insults, particularly on Twitter, in an attempt to pressure journalists into silence. A recent IPI feature, based on a preliminary content analysis, identified three types of verbal insults employed in Turkey: intimidating insults, defined as messages that include labels such as “traitor”, “terrorist” or “terrorism supporter” and “kafir” (infidel); humiliating insults, which are intended to belittle journalists using less loaded terms such as “bastard”, “asshole” and “son of a bitch”; and sexual-related insults.

Scrutiny of sexual-related insults is particularly important given that previous studies have highlighted a strong gender component to online harassment. Female journalists are frequently targeted for both their journalism and their gender.

@banuguven Kimse sana dokunmaz, şeyimizin de bir şerefi var o kadar düşmedik rahat ol, sen APO piçine layıksın dokundurt.

Nobody would touch you, even our penises have their pride. We have not lowered ourselves that much. Take it easy, you deserve the bastard Abdullah Öcalan, get yourself touched.@nevsinmengu Sanal kabadayılara el atılacak acele etmeyin. Darbe sevici, pkk sevici, orospu Nevşin, en başta seni sikecezzz merak etme. (Silah emoji)

@nevsinmengu Cyber rowdies will be taken under control, don’t hurry! A coup lover, a PKK lover, bitch Nevsin, we will fuck you first, don’t worry! (Gun emoji)

Our monitoring also examined the use of fake content, i.e., content falsely attributed to the target so as to discredit or defame him or her. IPI researchers in Turkey recorded a total of 31 instances of fake content. In one example, supporters of Turkey’s current government used an image of former Economist Turkey Correspondent Amberin Zaman – a frequent target of online trolls – to create the fake composition below.

Technical interference

The ongoing study collected 11 instances of digital attacks against media in Turkey, encompassing attacks directed at the technical infrastructure of news websites (such as DDoS) attacks as well as attempts to hack journalists’ social media accounts.

Nine out of these 11 instances related to attacks on individual journalists. These attacks mostly took the form of hackings of the targets’ social media accounts, especially Twitter.

Frequently, hackers take control of the journalist’s account to post messages in the journalist’s name asking for “forgiveness” for the “sin” of critical journalism.

The database is one of three elements that comprise IPI’s Ontheline programme. Together with Globaleaks and Virtualroad, IPI also has developed a secure platform for journalists to securely and anonymously report online attacks against them. The third element is IPI’s advocacy work to counter online attacks. Through in-depth features, publications and multimedia content, IPI aims to raise awareness of this problem at the national and international levels. Ultimately, this work aims to develop, together with other international organisations, guidelines for media outlets, journalists associations and freelancers for coping with online harassment.