Photo: Ugandans living in Kenya protest the detention of Bobi Wine in Nairobi, August 23, 2018. EPA-EFE/Daniel Irungu

By Sanna Pekkonen, Helsingin Sanomat Foundation Journalism Fellow at IPI

September 10, 2018

Last month, Uganda found itself thrust into the international spotlight, first by the arrest of prominent opposition figure and musician Bobi Wine – and then by multiple, shocking attacks on journalists covering the resulting political turmoil.

Those attacks were widely condemned internationally, but in interviews with the International Press Institute (IPI), Ugandan journalists say recent events are only part of a growing assault on media freedom in the country.

The latest wave of attacks against journalists in Uganda started ahead of a parliamentary by-election in Arua, a municipality located next to the border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Two days before the poll date, on August 13, the campaigning took a chaotic turn after Wine’s driver was shot dead. Wine, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, and several other opposition MPs were arrested on the scene along with at least two dozen other people accused of attacking President Yoweri Museveni’s convoy.

State security forces took their anger out on journalists at the scene as well. Journalists Herbert Zziwa and Ronald Muwanga from the television broadcaster NTV were reporting live on air from Arua when they were assaulted and arrested. The following day, they were charged with inciting violence and malicious damage to property before being released on bond.

At least three other journalists were also attacked in Arua. A member of the security forces reportedly hit NBS TV journalist Bakabaage Julius on the head with a baton, while two of Julius’s colleagues, John Kibalizi and Benson Ongom, were allegedly chased by the security forces.

Reuters photojournalist James Akena was among journalists assaulted by Ugandan security forces while reporting from the demonstrations in Kampala on August 20, 2018. (HRNJ-Uganda)

Attacks against journalists continued when the detention of the opposition politicians and the accompanying violence sparked protests across Uganda. At least five journalists were assaulted by army and police officials while covering the protests in Kampala, the country’s capital. Several also had their equipment confiscated and material deleted or removed.

Further still, journalists covering these incidents and the political turbulence in the country more broadly have reported receiving threatening phone calls. A list of journalists allegedly participating in a plot to overthrow the government has circulated on social media, exposing those named to attacks by government supporters.

The attacks on journalists have outraged the Ugandan media community. Robert Ssempala, executive director of Human Rights Network for Journalists Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda), a press freedom group, said in an interview with IPI that the latest attacks underscored the pressure on the media environment.

“The situation is deteriorating by the day. It all seems to criminalize the work of journalists”, Ssempala said.

Daniel Kalinaki, executive editor for the Nation Media Group (NMG)’s operations in Uganda, described the recent attacks as merely the escalation of a long-running campaign against critical, independent media in Uganda. NMG itself has been affected: Two of the journalists arrested in Arua worked for the NMG-owned broadcaster NTV. Kalinaki emphasized that the NTV journalists were only doing their job when they were attacked.

“The government of Uganda seems to think that – and certainly acts as if – journalism is a crime”, Kalinaki told IPI.

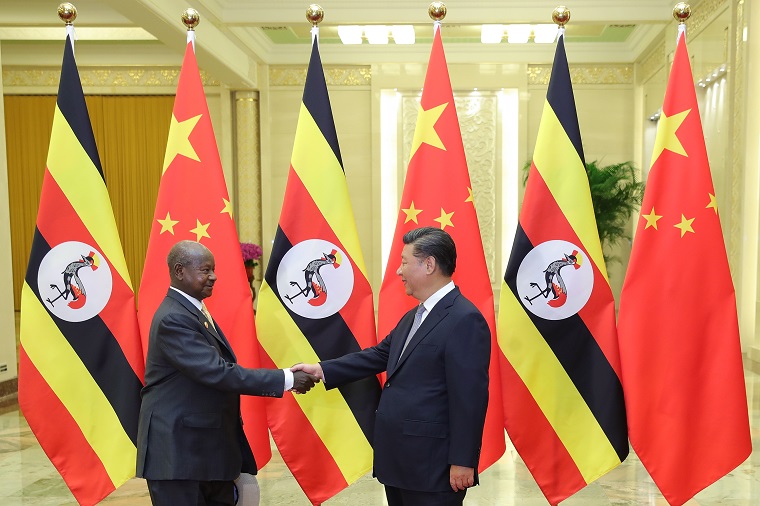

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni (L) with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a recent trip to China. EPA-EFE/Lintao Zhang/Pool

The Ugandan army later issued a statement apologizing for security forces’ conduct toward journalists in Kampala, but HRNJ-Uganda warned that it would start peaceful, nation-wide protests and boycotts if the officers responsible weren’t arrested and brought to justice. The group abandoned the protest plans after the Ugandan People’s Defence Forces offered assurances during that the officers would be punished.

Nevertheless, only days after the agreement, police officers beat Joshua Mujunga, a photojournalist working with NBS TV, with sticks while he was covering protests in Kampala.

ATTACKS GROW MORE SEVERE

Attacks on journalists are not new in Uganda. In 2017, HRNJ-Uganda recorded 113 press freedom violations, including detentions, assaults and equipment damage. The Ugandan police were responsible for the vast majority of those violations, with many of the perpetrators going unpunished.

Still, Ssempala told IPI that attacks on journalists had grown more severe this year. A new, worrying trend involves kidnapping journalists to interrogate them and scare them off from reporting about certain subjects.

Stanley Ndawula, CEO and editorial director of the online publication Investigator, was recently subject to this tactic. On one Friday evening at the end of July, he was driven away at gunpoint from the restaurant and bar that he runs alongside his newspaper.

“The government of Uganda seems to think that – and certainly acts as if – journalism is a crime.”

In an interview with IPI, Ndawula said he was held in captivity for two days. Although he initially thought his kidnappers were restaurant customers, it turned out that he had, in fact, been detained by state security agents. Those agents interrogated him over a story he had written on a businessman allegedly tortured by Uganda’s Internal Security Organisation. Ndawula was finally released after he had been taken to see the director-general of the security agency, Colonel Kaka Bagyenda.

“Uganda is turning into a state of terror when it comes to journalism”, Ndawula said.

POLITICAL UNREST

Political tensions in Uganda grew with the turbulent 2016 presidential election, which was tarnished by widespread accusations of voter fraud. They became palpable again late last year when the country witnessed a violent debate over the age of presidential candidates.

The ruling National Resistance Movement party pushed a bill to eliminate the 75-year age limit for presidential candidates from the Ugandan Constitution as Museveni, in office since 1986, would exceed that limit before the next election. The initiative evoked political and popular opposition, and many young Ugandans took to the streets in protest. Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine), whose driver’s murder sparked the unrest in Arua, was one of the leaders of the movement against the bill, which was approved despite the criticism.

Ugandan security forces on patrol during the February 2016 presidential election. EPA/Dai Kurokawa

Ugandan journalists say that government pressure has intensified as a result of the age-limit debate, which state actors sought to control by introducing reporting restrictions on the media. The Uganda Communication Commission (UCC), the government telecoms and broadcasting regulator, ordered a ban on live coverage of parliamentary debate on the age-limit proposal and issued guidelines to stop the media from interviewing MPs who opposed the bill.

“Politicians are using their power and influence over the free, legitimate work of media houses”, Ssempala said.

Part of the problem, journalist say, is a law passed in 2016 that allows the government to introduce new regulations to the communicators sector without seeking approval from parliament. According to HRNJ-Uganda’s analysis, the UCC has exercised this power by issuing “guidelines” to media houses as well as by suspending journalists and broadcast licenses from certain media houses on the pretext of public safety.

HRNJ-Uganda is currently preparing to file a case with the Ugandan Constitutional Court questioning the power and mandate of the UCC.

“The UCC is not working for the media but against the media”, Ssempala, the group’s director, said. “That is not what we expect of the UCC.”

OPPRESSIVE LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The UCC and the police have also resorted to slapping journalists with criminal charges to prevent them from reporting on certain subjects. In particular, the Penal Code Act, the Computer Misuse Act and the Uganda Communications Act have recently been used against the press. HRNJ-Uganda has said that vague language in these laws has allowed them to be used to curtail free expression.

Last November, the Computer Misuse Act was invoked to raid the premises of the newspaper Red Pepper after the paper published an article claiming that President Museveni was plotting to overthrow his Rwandan counterpart, Paul Kagame. (The paper says it picked up the article from a Rwandan online publication.)

“As long as you are praising the regime or the administration, things are OK with you. Talking about infrastructure and development is what they call good journalism. But when you enter the arena of power and accountability, you are falling into trouble.”

Five directors and three editors of Red Pepper were detained and charged with various offences, including publication of information prejudicial to national security, libel and offensive communication. The journalists spend almost a month in detention before being released on bail, one of the directors, Arinaitwe Rugyendo, told IPI.

“Later on, we went to negotiate with the state to get our publication back to the street”, Rugyendo said. The case never proceeded to court.

The government reportedly used a similar form of pressure on Stanley Ndawula from The Investigator last year. Ndawula and his brother were detained for several days under the Computer Misuse Act over their coverage of police after the latter filed charges of “offensive communication” against the journalists. Ndawula told IPI that the case was eventually dismissed after numerous court hearings.

Notably, the Computer Misuse Act has been used not only to scare journalists, but also to directly limit coverage of certain issues. Last year, a court ordered Red Pepper, The Investigator and Chimp Report to stop reporting on the murder of a police officer that reportedly pointed to criminal activity within the police itself.

TABOO TOPICS

Both Red Pepper and The Investigator have been able to continue publishing their paper in print and online, but they still face challenges in the aftermath of the recent incidents.

“Sometimes we don’t come out (with an edition) because the printing machine was completely dismembered (in the raid) last year”, Rugyendo told IPI. “We might go two days without publishing.”

What is more chilling is the way in which the state intimidation has affected the journalists’ work: Self-censorship is becoming more common.

“The stories that we used to publish we cannot publish anymore”, Rugyendo said. “We have strict criteria on all stories related to national security, because it is not certain how the state will react. Press freedom in Uganda is under state intimidation. The pressure comes especially from the security forces.”

Map: OCHA

Another Ugandan journalist, who requested anonymity for this article, told IPI corruption, impunity or government accountability are subjects that lead to problems.

“As long as you are praising the regime or the administration, things are OK with you”, the journalist commented. “Talking about infrastructure and development is what they call good journalism. But when you enter the arena of power and accountability, you are falling into trouble.”

There is also the issue of what some say is “dishonesty” within the profession, referring to persons in the media who largely serve as government mouthpieces and even attack the independent press. Financial sustainability and, in some cases, a lack of support from media owners also create challenges for independent journalism.

“Lack of financial muscle in smaller media houses leaves them vulnerable to corruption and intimidation”, Kalinaki said.

CONTROVERSIAL ‘SOCIAL MEDIA TAX’

Press freedom has long struggled to flourish in Uganda, but many journalists feel that the situation has deteriorated over the past couple of years. NMG’s Daniel Kalinaki noted that the situation in Uganda was still better than in some neighbouring countries.

But, he added, “the journey to hell is paved with impunity and silence in the face of oppression and injustice”.

The Ugandan government appears to be interested not only in controlling journalists, but public discussion as a whole, too. One example is a new tax on social media. Since July, people using social media apps such as Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp have been charged USh200 (equivalent to 0.05 euros) per day, or around 18 euros per year in a country with a per capita GDP of around 525 euros. The government has said that the tax was introduced to stop “gossiping” on social media and to earn revenues for the state. Critics believe that the real reason was to limit the freedom of expression.

The effects of the tax can already be seen.

“It has definitely limited the access to the means of communication as well as ability to source news and information”, Rugyendo said of the measure.

In these turbulent times, local media organizations have sought common ground with President Museveni within a new body called the Presidential Media Roundtable. Its first meeting was held in May this year whereupon Museveni urged journalists to help Africa “rise and shine”, while media representatives expressed their concern over shrinking press freedom. The journalists IPI interviewed for this article were sceptical about the meetings’ potential outcome.

Many journalists felt that more cooperation within the media industry and among journalists is urgently needed to restore what is left of the free press in Uganda.

“I would want the journalists in Uganda and in East Africa to unite and to fight the cause”, Ndawula said.

The production of this article was supported with funds from the Helsingin Sanomat Foundation as part of the Helsingin Sanomat Foundation Fellowship Programme at IPI.