May 2018 brought new hope for media freedom in Malaysia with the unexpected electoral defeat of the Barisan Nasional coalition, which had ruled the country for 61 years. The new ruling coalition, Pakatan Harapan, led by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, promised progress and reform, including in the area of fundamental rights. More than one year later, how has the situation for journalists changed?

Prior to 2018, Malaysian journalists operated in an unfree environment, with much of the media under government control. “For 60 years, under Barisan Nasional rule, press freedom in Malaysia continued to be on the decline”, journalist Alyaa Abdul Aziz Alhadiri of the online media portal Malaysiakini said in an interview with the International Press Institute (IPI).

Media observers say that the overall climate has now improved. Informal pressure and self-censorship have decreased. “There is an air of openness after long periods of carefully walking on eggshells when it came to politically charged coverage”, Gayathry Venkiteswaran, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham in Malaysia told IPI.

That openness extends to officials’ personal approach to the media. “Prime Minister Mohamad is a big difference compared to the former premier (Razak) as he is always willing to answer any questions thrown at him, on any issue” Alhadiri noted. “This has allowed the media the opportunity to clarify many issues on national policies and the day-to-day running of the country.”

Yet Malaysia has failed to make progress on one particularly significant front: the repeal of repressive media laws, among them the country’s controversial new Anti-Fake News Act, whose vague definitions allow the government to suppress any content it deems “fake”. Abolishing the latter measure was one of the new government’s key commitments. Malaysia’s lower house of parliament voted to repeal the Anti-Fake News Act last year but was overruled by the upper house, which is controlled by the opposition.

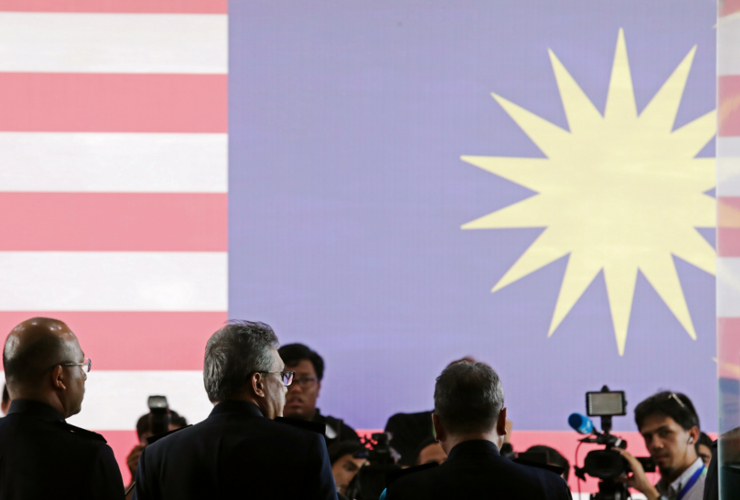

Prime Minister Mohamad vowed earlier this year to press ahead with repeal despite the initial rejection, a sentiment echoed by the country’s communications and media minister, Gobind Singh Deo, on the sidelines of the Global Media Freedom Conference in London in July. Describing the Anti-Fake News Act as “a piece of legislation hastily enacted by the previous government to clamp down on the press the opposition and civil society”, Singh insisted that even as repeal remained pending, the law was effectively dead letter.

Repeal of oppressive laws stalls

Although the government has said repeal of the Anti-Fake News Act remains a priority, it has not addressed several other problematic measures. Pakatan Harapan’s election manifesto pledged the abolishment of a number of “tyrannical laws” but the pace of reform has been slow.

Concretely, the ruling coalition had vowed to abolish six laws under Promise 27 of the manifesto, two of which are highly significant for the media: The Sedition Act 1948, and the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 (PPPA).

The Sedition Act was introduced during the British colonial period and was aimed against communist insurgents. The Barisan National coalition had been accused of using the law’s vague definitions to punish any act, speech or criticism that showed government in a bad light. Backtracking from its manifesto, the new government lifted a self-imposed moratorium on use of the law last year. More recently, Prime Minister Mohamad said that the government would study the suitability of repealing and replacing the law.

Abolishing the PPPA is also of great significance for press freedom. The measure stipulates that print publications require a permit from the government to operate, which can be revoked or suspended at the government’s discretion.

“It is problematic that we haven’t seen more movement in the legal reforms, especially in the case of the PPPA and the Sedition Act”, Venkiteswaran said. “Part of the challenge is that these laws have been framed as national security laws, and even this government seems reluctant to move ahead with the reforms although it has given assurances that the changes will be made.”

In July, the government also announced plans to replace the Official Secrets Act 1972, which gives the government wide-ranging powers to declare information confidential and foresees severe penalties in the case of publication, with a Freedom of Information Act.

Speaking in London, Minister Deo acknowledged that “we need to do more to push ahead with our reform agenda when it comes to press and media freedom. Two of the main areas that I am looking at is to ensure that all those laws that are required to be amended and abolished are acted on as soon as possible, and also the setting up of the media council.”

Progress toward media self-regulation

The minister’s mention of the media council refers to the party’s promise to set up a media self-regulatory body, the enaction of which would be a stark contrast to Malaysia’s previously state-heavy regulation model, embodied by laws such as the PPPA. Last month representatives of the prime minister met with interest groups to discuss the proposals for such a council, with the hope of having lawmakers take action by the end of the year.

Media representatives remain cautious about the plan’s prospects. “We need a media council that can regulate the ethics of media in a meaningful way”, Sonia Randhawa, director of the Malaysia-based Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ), said in an interview with IPI. “We need journalists and editors present, but the public needs to be represented as well. At the moment, there is a lot of debate and discussion about this issue, and CIJ is concerned that we might not see that happen.”

Others argued that the formation of the media council, while welcome, should not distract from the need to improve media legislation. And Randhawa underscored that repeal of the Sedition Act and the PPPA are “two really easy things to do to show the government’s goodwill. Both are colonial-era pieces of legislation to prevent discussion of key public issues. We don’t need them, never needed them and they certainly have no place in a democracy.”

IPI Director of Advocacy Ravi R. Prasad echoed that view.

“We urge the Malaysian government to uphold its promises and expedite the efforts to get rid of the archaic laws that impede freedom of expression and press freedom”, he said. “The new Malaysia can only be democratic if such laws are repealed quickly and media allowed to perform its job without any fear.”