This September, a cross-border team of investigative journalists exposed massive fraud in European Union-funded projects in Bulgaria and Romania in what became known as the #GPGate scandal. The revelations shed light on alleged extensive corruption in the construction sector, but they also underscored the difficult press freedom situation in Bulgaria. The safety of the investigative team came under threat, and in October, the country witnessed the gruesome murder of a television journalist, Viktoria Marinova, who reported on the #GPGate scandal .

The #GPGate affair started unfolding when a team of five Bulgarian and Romanian journalists led by the investigative journalism websites Bivol and RISE Project Romania got hold of leaked accounting books of a network of consultancy firms. The data provided evidence of large-scale and wide-spread corruption in EU funded construction projects involving construction giants, most importantly the Bulgarian GP Group, hence the name.

In a recent interview with the International Press Institute (IPI), Atanas Tchobanov, editor-in-chief of Bivol, said the findings indicated a clear pattern of corruption in EU-funded projects in Bulgaria.

The investigation found that companies with ties to the GP Group handed out bribes and manipulated public procurements for the construction of buildings, roads, water pipes, and landfills so that the deals were secured by certain large construction companies. The schemes were concealed with double accounting, according to the team’s research.

The work of the investigative team was financially supported with a €38,000 grant from IJ4EU, a fund backed by the European Commission via the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) and managed by IPI. IJ4EU, which launched in 2018, aims to support cross-border investigative journalism in Europe.

The money invested has already yielded remarkable results: Tchobanov estimated that €400 million worth of EU-funded projects had been halted or was under scrutiny due to the #GPGate revelations.

Still, Tchobanov said he was not yet satisfied with the outcome.

“We are satisfied that the impact is there, but we want a serious investigation (into the allegations)”, he told IPI. He questioned the commitment of the Bulgarian authorities to such an enquiry. “If they do not want to secure the evidence, they are not really investigating this.”

Illegal detention

Tchobanov’s doubts about the authorities’ commitment refer to a series of events that unfolded shortly after the first #GPGate story was run on September 10. The investigative team started to receive tips that GP Group was moving documentation and equipment from its headquarters in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital. A few days later, they heard that the material was being burned in a field in Radomir, western Bulgaria.

The journalists notified the authorities. “But the police said they did not have time to send people there”, Tchobanov said.

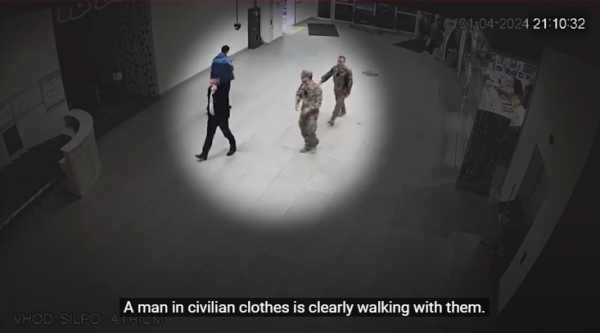

Then, after two members of the team, Bivol reporter Dimitar Stoyanov and Rise editor Attila Biro, arrived in Radomir to document the events, they were confronted by police. But instead of trying to prevent the destruction of the evidence of massive fraud, officers detained the journalists.

A leaked document shows that Bulgarian prosecution did NOTHING to prevent the destruction of evidence about #GPGate. They ignored our reporting until 14/09 (after the arrest of our journalists) and opened official pre-trial proceedings only after the death of #ViktoriaMarinova pic.twitter.com/Bcd7gxgu0K

— Bivol (@BivolBg) November 22, 2018

The police refused to release Stoyanov and Biro despite being presented with press cards, and confiscated their mobile phones. They were eventually freed in the early hours of the next day. Last week, a court ruled that the detention orders were illegal.

Soon after the incident, the team rushed to publish their second #GPGate story.

“We got a tip that we were under a serious threat”, Tchobanov said.

The next report showed how EU funds circulated from consulting companies to offshore corporations and how GP Group was linked to oil company Lukoil’s Bulgarian branch as well as Russian billionaires and names associated with organized crime circles.

Doubts about a murder investigation

Although Bulgarian media picked up the #GPGate story at first, public discussion fell silent quickly. One of the few journalists to dig deeper into the case was Viktoria Marinova, the host of an investigative programme on the broadcaster TVN. On October 1, Marinova invited two members of the #GPGate team on her show.

The next weekend, Marinova was brutally murdered. Her body was found near a river in Ruse, a city in northern Bulgaria near the Romanian border.

“The first thing we thought was that it was intimidation by example”, Tchobanov said.

In October, Bulgarian police arrested a man whom they identified as the prime suspect. The man reportedly claimed to have been under the influence of alcohol and drugs and the time of the attack. Authorities do not currently believe Marinova’s murder was linked to her work.

Tchobanov, however, remains suspicious of the murder investigation, saying that police appeared not to have fully looked into the possibility of a contract killing. He also stressed apparent inconsistencies in the official version of the murder: Police have called the killing a spontaneous act, but have also said the suspected killer was waiting for Marinova in the bushes.

“How can it then be spontaneous? Something doesn’t add up. Nobody can say reasonably that the case is solved”, Tchobanov said. “We want an independent European body to investigate the case.”

Both IPI and the expert jury that oversaw the IJ4EU grant selection have said the murder investigation must consider all angles, including the possibility that Marinova was killed in connection with her work.

Since the murder, public discussion on the misuse of EU funds in Bulgaria has stopped.

“No one is speaking about it”, Tchobanov said.

Impunity prevails

Threats to the safety of investigative journalists are not new in Bulgaria. Most recently, in May, journalist Hristo Geshov was beaten outside his home in Cherven Bryag after he reported on alleged corruption of EU funds involving Cherven Bryag’s municipal government. Last December, journalist Maria Dimitrova was also threatened after she collaborated with Bivol for a story about a drug trafficking group. Prosecutors declined to pursue the threat case.

“There is not a single case of attack against a journalist in Bulgaria that has been resolved”, Tchobanov told IPI. “There is an atmosphere of impunity in crimes against journalists.”

Handcuffed for investigating #EUFunds fraud in #GPGate. D. Stoyanov from @BivolBg and @Biro_A from @OCCRP partner @riseprojectro attending @EP_Justice exchange of views in @Europarl_EN on situation with threats against investigative journalists. pic.twitter.com/FtgNfyYzMS

— Bivol (@BivolBg) November 21, 2018

Tchobanov said media freedom in Bulgaria was also limited by the concentration of media ownership in the hands of a few powerful businessmen whose outlets tend to promote the government agenda. Refraining from asking critical questions also furthers better advertisement revenues, he added.

“It is very difficult to hear critical voices in Bulgaria. They exist but you cannot hear them on the TV or radio. Only Facebook is not controlled by the government.”

In early November, Bulgaria’s parliament passed a law requiring media outlets to declare their sources of income. Bivol has protested about the move and has said it will refuse to disclose information about its funders, including 2,000 individual donors.

“We don’t want to expose those people. They can be intimidated”, Tchobanov said. “The law is designed to scare the people who are doing crowdfunding, like us.”

Private actors have also recently questioned the credibility of Bivol’s funding, including the IJ4EU grant. In a recent letter, IPI and ECPMF urged the Bulgarian Construction Chamber to refrain from attempts to undermine Bivol’s reporting after the Chamber called the site’s funding “vague” and “opaque”.

Safeguarding evidence

Bivol and RISE Project Romania are now working on the next phase of the #GPGate stories.

“We are following the companies involved in European money fraud, but we are not rushing it”, Tchobanov said.

Last week, two GP Group shareholders were indicted for money laundering by Bulgarian prosecutors, allegedly in connection with the GPGate affair. Their names were not revealed.

Journalists on the team continue to face pressure. This month, after RISE Project exposed alleged EU-fund fraud possibly involving a prominent Romanian politician and a Romanian construction firm, Romania’s data protection authority ordered the site to reveal its sources or face up to €20 million in fines.

To safeguard the team, their sources and the evidence, Bivol and RISE Project Romania have handed over relevant documents related to #GPGate to the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), an EU body mandated to detect and investigate fraud involving EU money.

“Now these people know that the evidence is not only in our hands and the revenge would not give the result they wanted”, Tchobanov said.