The Croatian government is looking to criminalize unauthorized leaks of material from criminal proceedings. While the authorities insist that the new law will protect the presumption of innocence, media professionals and numerous law experts decry the proposal, warning it will silence journalists and their potential sources. The outcry over the “anti-leak” legislation comes shortly after the Culture and Media Ministry released a proposed draft of the new media law, which media associations labeled as “unprecedented state interference in journalistic freedoms”.

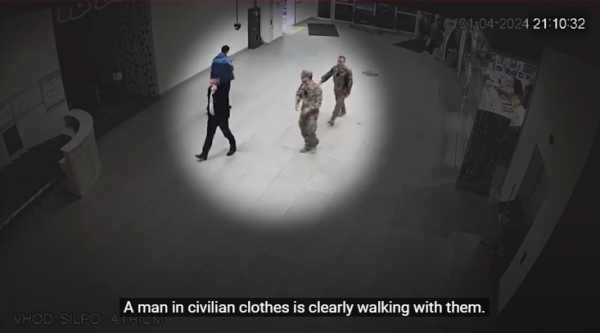

In February 2023, Croatia´s Prime Minister Andrej Plenković announced changes to the Criminal Code that would criminalize unauthorized disclosure of the content of investigative or evidentiary action. The declaration followed a highly mediatised leak of text messages from January 2023, which was used as evidence in an investigation launched by the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, and ended up being somewhat embarrassing for Plenković. In the leaked correspondence, former EU Funds and Regional Development Minister Gabriela Žalac, caught up in a corruption probe over an allegedly inflated cost of software, makes a mention of a certain “A.P.”

Fast forward to September 2023. The law, dubbed ‘Lex A.P.’ in the media, after the initials of the Prime Minister, was submitted to a public consultation, and instantly alarmed journalists and law practitioners. “This law of silence that the government wants to pass is an attack on the journalistic profession and public interest,” said Hrvoje Zovko, the president of the Croatian Journalists’ Association (HND) in a phone interview with IPI.

The Prime Minister stated explicitly that the proposed changes to the law, which envisage punishment of up to three years in prison, would not target the media. However, “the proposed bill doesn’t include any protective clauses for journalists, and will dissuade potential sources from talking to them,” said Zovko. He stressed that this could make it possible to seize and search journalists’ communication tools – phones or laptops – in order to reveal the source of the leak. The Supreme Court judges also criticized the law proposal, stating that if no clause specifically stipulates the protection of journalists, the proposal leaves a possibility for them to be considered instigators or ‘guilty by association’.

The current Criminal Code already contains punishments for the violation of the confidentiality of proceedings (including evidentiary actions), as well as for the unauthorized disclosure of professional secrets, official secrets, and other secret information. This means, concretely, that a police officer can’t reveal that a defendant in a proceeding for drug trafficking is being secretly tapped, either to the defendant or to the media.

“If he did, he would be criminally liable”, explained Igor Martinović, associate professor at the Faculty of Law in Rijeka, Croatia. “But the proposed law changes would prohibit the public disclosure of any relevant information regarding the proceedings before the indictment is filed,” he told IPI in an email. “This would ban defendants from publically presenting their version of the story. If a victim, for example, submitted a video of the violence they suffered to the media, and if that video is also evidence in the proceedings, the victim would be liable for a criminal offense,” he added.

If the criminal proceedings were to start on the basis of the whistleblower’s report, the whistleblower would become a witness. Both the whistleblower and the journalist to whom he would pass on any information about the case would be in trouble. “It is difficult to predict what exactly would happen in that case, because the Act on the Protection of Whistleblowers provides for the protection of whistleblowers (…) but the atmosphere of fear would surely increase among potential whistleblowers and journalists,” believes Martinović. And while the new proposal states that the disclosure of information will be possible after the indictment becomes legally binding, that is a small comfort in a country where the judicial system is notoriously slow, and where corruption is still rampant (Croatia ranks 57th out of 180 countries on to the Transparency International 2022 corruption index).

New media bill on hold

At the same time, the media representatives are still waiting for updates on the new draft of the media law that the Croatian Journalist Association (HND) deemed “unacceptable”. The controversial draft suggested creating a registry (photo)journalists, with a special committee deciding on who would be approved as a (photo)journalist, and granting the right to publishers not to publish a journalistic piece without any explanation.

“This is a legalization of censorship,” said Zovko. “The draft also mentions that the journalists would be required to reveal their sources not only to their editor-in-chief but also to the publisher.” The current media law stipulates that journalists might need to reveal information on the source to the editor if the source is anonymous. Also, the courts might compel a journalist to reveal a source, if no alternative is available, to protect national security, territorial integrity, and public health.

The draft, penned by the Ministry of Culture and Media, seems to have been put on hold. “The HND sent their comments on the proposal at the end of July. We were told that the working groups would meet soon after, but nothing has moved forward since,” said Zovko.

When it comes to the “anti-leak” legislation it is yet to be debated in the Parliament. For both legislative changes, the stakes are especially high at the moment, Croatia is entering a ‘super election’ year in 2024. The country of just under four million people will vote at the European elections in June, at the parliamentary elections in August or early September, and at the presidential elections in December.

This article was commissioned by IPI as part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States, Candidate Countries, and Ukraine. The project is co-funded by the European Commission.